Less is more: the art of removing the unnecessary from your music

Learn to embrace minimalism and find your focus with our guide to stripping back your sound

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Without silence, there is no music. This is true in physical reality as well as music theory. After all, playing back all possible frequencies at once results in white noise. Even in the densest mix, it’s what’s not there that defines the song.

In essence, making music can be talked about in the same way that Michelangelo talked about carving David, his towering masterpiece of Renaissance sculpture. Starting with raw marble, the artist simply “removed everything that is not David”, stripping away the unnecessary to reveal the artwork’s essential form. “I saw the angel in the marble and carved until I set it free," Michelangelo is quoted as saying.

This is to say that silence is as important to music as sound. Knowing this can help us craft more powerful arrangements and mixes since it means part of our job is removing things. In modern music, this kind of clarity and spaciousness is huge, especially given the intimacy of earbuds and headphones. Of course, removing noise has always been job number one for mixers, so this concept is nothing new to them – but let’s start at the beginning.

Finding the focus

Before you know what you don’t need, you need to know what you do need. So, you may find it helpful to determine the focal point of a song before it’s even written. What’s the main driver? What’s the goal of the song? Will it be a touching, intimate portrait? Will it be an epic banger with an ecstatic rapper leading the charge?

Not all songs are written this way, of course, but whether this happens before or after lyric and melody, at some point a direction needs to be set. Knowing this, you’re armed with a solid focus that gives you an idea of what you’ll need in the arrangement and then the mix.

For example, it’s unlikely you’ll need an ear-blasting guitar solo for that intimate ballad. It’s equally unlikely you’ll need a glockenspiel for the rap-rock banger (although now that we’ve said that it’s certain to happen and be amazing). In this sense, you’ve removed before needing to remove.

Songwriting

It’s not just production that could often do with a dose of minimalism. Songs themselves are also prone to extra – extra words, extra notes, extra chords, extra verses. Of course, whether a song should be overly ornate and densely Baroque in style or as minimal as Reich or Glass is a matter of taste and function, but if you’re looking to make space, you might as well start with the song.

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

This isn’t to say there’s no place for flourish or intricacy: removing superfluous elements can make room for more focused complexity

For example, perhaps portions of a melody can be inferred – removing notes in this case can make space and create a unique flavour. Similarly, there are many ways to say the same thing in a lyric – removing syllables or simplifying the message itself can make space for pauses, instrumental answers, and if you’re thinking ahead, lush reverb tails or stark silences. Fewer words or notes can also give singers an opportunity to play with delivery, breathe more, and bring an extra dimension of creativity to a performance.

This isn’t to say there’s no place for flourish, intricacy, or dense syllabic virtuosity. Indeed, removing superfluous elements can make room for more focused complexity.

Arrangement and recording

If you’ve had a focused goal from the beginning, arranging a tune may be straightforward. Pre-defining a song as an “intimate piano ballad” pretty much gives you the instrumentation. Still, there are a lot of ways to use that piano. Will you fill space with complex arpeggios, or go with simple, one-measure chords? Will you create a booming low end with the lowest octaves, or keep it sparse and light with the higher keys?

9 minimal track arrangement tips: find out how a little can go a long way

Again, the arrangement is an opportunity to remove ‘that which is not David’ before you even put marble in the DAW. Many artists and producers skip this step or choose to let the band go hog-wild in tracking, but it can be helpful to focus things in this stage and carefully craft the arrangement before the mix stage. For example, try letting the band run through a couple of rehearsals to see what they do. Guaranteed every player will play through the whole song. Now start instructing players (and notating) when not to play to carve out a dynamic arrangement.

Even if you want a huge sound, that may be better achieved with a smaller palette in some cases. One huge floor tom, for example, creates a big, wide, focused boom, whereas that tom competing with a kick, bass, and low-end synth forces you to make everything smaller to work together. Of course, you can leave these decisions to the mix engineer - and that’s a valid choice if you trust them - but doing it before tracking will make the mix faster, and possibly better.

Mixing

A mixer’s job varies depending on who’s hiring them, but it often involves dealing with way too much information. For many, the goal of mixdown is to make the song sound “like a record”, which means cohesive focus alongside clarity and separation. Most of the time, that’s all about removing stuff, starting with EQ.

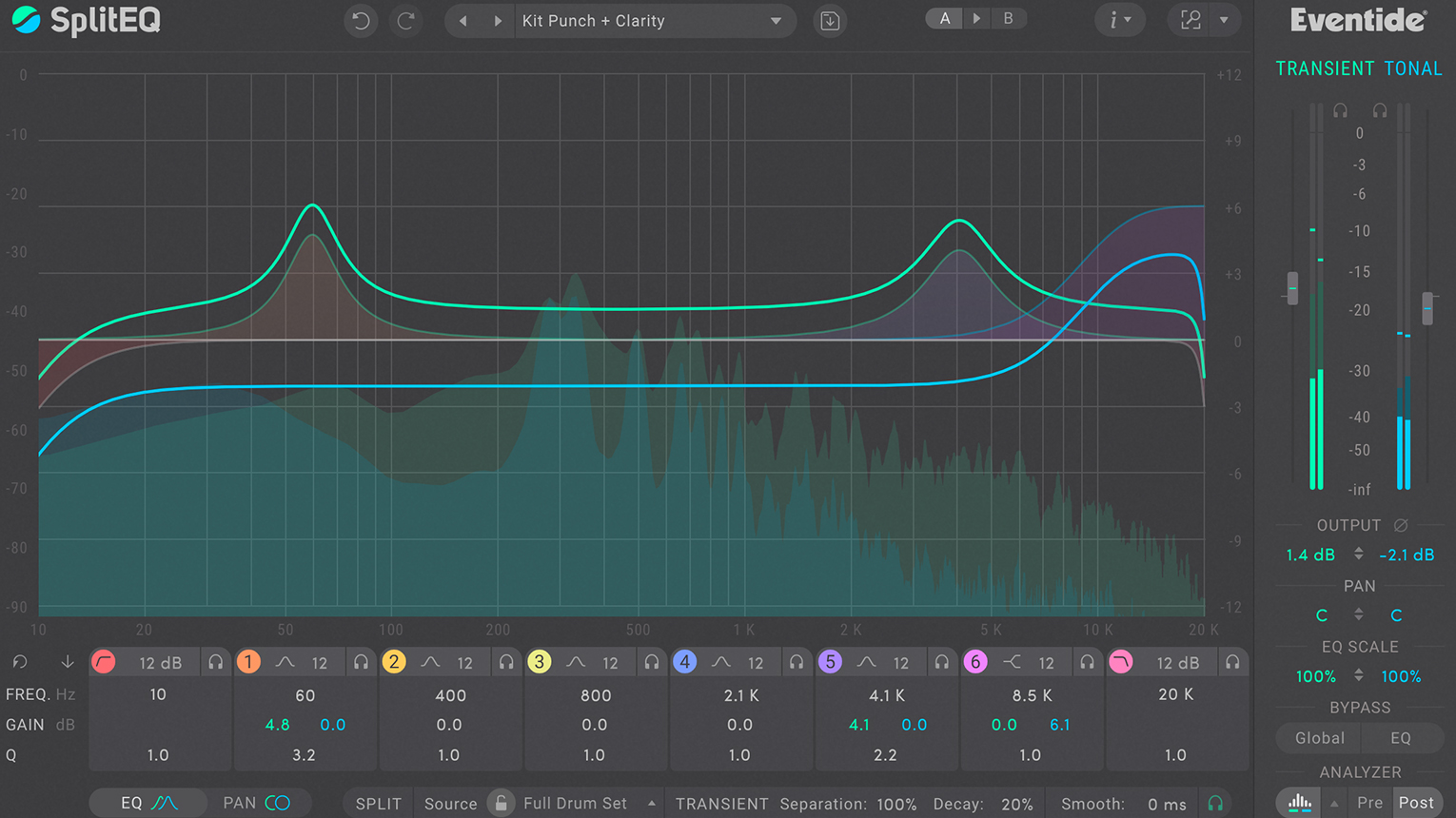

Subtractive EQ is the unsung hero of mixing. In almost every mix, vocals get high-passed, drums and bass get notched so they don’t interfere with each other, and ugly frequencies, boxiness, or odd resonances are removed with judicious cuts. It’s all about taking away what isn’t David.

Once tracks are carved out, one oft-overlooked opportunity to create space is on the effects bus. Reverbs especially can add a lot of extra fluff that obfuscates a mix, so one not-so-secret EQ trick mixers love is the old ‘Abbey Road Trick’, thusly named because it was reportedly invented by engineer Geoff Emerick during the recording of The Beatles' album Revolver.

The technique is simple – apply an EQ before the reverb on the bus and apply a high and low pass filter, thus sending a bandwidth-limited signal to the reverb. This and similar techniques are an easy way to remove what’s unnecessary from effects, leaving room for what serves.

'Underdubbing'

‘Underdubbing’ (not to be confused with the fly fishing technique) is a term used by some mixers to mean removing material from raw tracks. This could mean throwing away whole tracks, comping takes or deleting sections from some instruments, say if a keyboard is playing through the whole track and it’s not needed in the verses.

In the absence of focused songwriting and arrangement, mixers often save an otherwise lacklustre mix by removing material. They can become de facto arrangers, and even when they’re not allowed much creativity, some underdubbing is often necessary.

Some artists or producers, for example, send multiple takes for the mixer to choose from. Some forget to remove bad takes. Some track a hundred guitars with the idea that more is always better, and mixers achieve the huge sound they want by deleting ninety-eight of them.

Carving angels takes practice

Knowing what to remove is as much an art as a science. Mixers know to high-pass certain tracks when low-end information isn’t contributing anything, or to use ducking to get the bass out of the way when the kick hits.

But more than that, mixers, producers, and artists should learn to recognise when sections, takes, lyrics, or instruments don’t serve the goal. This can be difficult – it takes guts not to use a virtuosic solo when it doesn’t serve the song. But making great music is just like making anything else. It’s often all about getting stuff – and yourself – out of the way.

Aaron J. Trumm is an artist, producer, and writer. He’s been making records since ADATs were fun, was once a cowboy gunfighter bad guy, and his techno/spoken word project Third Option was called "wicked, totally compelling" by BBC I's Annie Nightingale. Talk to him about all of it at aarontrumm.com or social media @AaronJTrumm.