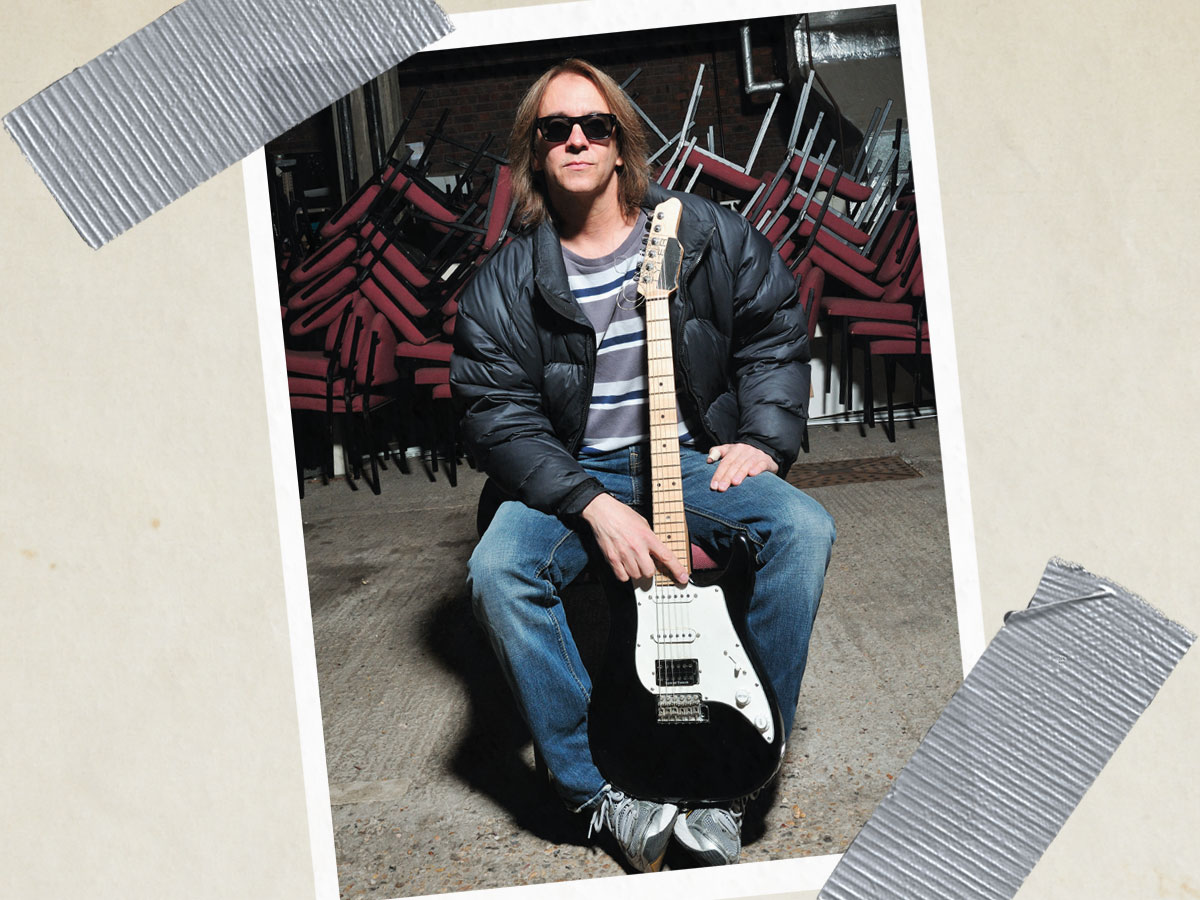

Wayne Krantz on jazz guitar, improvisation and creative practice

The jazz pro discusses his guitar philosophy

Introduction

When it comes to pioneering improvisation, ear-catching fusion and astounding jazz guitar chops, they don’t get much better than Mr Wayne Krantz. The six-string virtuoso gives us a few lessons in his key of life...

Wayne Krantz is one of those guitarists who simply dazzles, leaving numerous other axemen wallowing in his wake. The jazz fusion genius’s fretboard mastery and edgy improvisational exploits have gained him a more than lofty reputation on the New York jazz circuit since he first emerged back in the mid-1980s.

Carla Bley, Billy Cobham, Michael Brecker and Steely Dan have all called on Wayne’s pioneering skills, while his own trios have wowed crowds wherever they’ve trodden the boards.

We catch up with Krantz as he releases his 10th solo album, Good Piranha/Bad Piranha. The long-player features two different trio line-ups, each tackling the same four tracks by MC Hammer, Ice Cube, Thom Yorke and Pendulum.

"I never really focused on the guitar... The thing that changed that, really, was when I started listening to jazz players"

It’s safe to say you’ve never heard a record quite like this, with musicians at the very top of their game showcasing truly electrifying improvisational skills. You can surely learn a lot from visionaries such as Krantz...

Some things are meant to be

"I was forced to take piano lessons as a child and I hated it, but my father had this acoustic guitar, which had literally just been left in the attic. Nobody pointed it out to me and nobody mentioned it, but I just kind of found it and started plucking around on it. I was immediately interested, and that was when I was 13 or 14 years old, I guess.”

Great guitarists appreciate the band as a whole

"As I was playing through high school and so forth, I wasn’t really very guitar-player conscious. I was very, very band conscious.

"As much as I loved Zeppelin and Jethro Tull, I never really focused on the guitar, and - even with the limited exposure I had to Hendrix at that time - I was really more thinking about the songs and the sounds of the songs and the band element rather than isolating the guitar.

"The thing that changed that, really, was when I started listening to jazz players, because jazz is much more about the players, and that’s when I started recognising, ‘Oh wow! That’s a good guitar player... okay, so that’s what’s possible!’

"That was after I went to Berklee [College Of Music, Boston]. That’s when Joe Pass, George Benson and John McLaughlin, and then Pat Metheny, Mick Goodrick and Mike Stern - the younger players from the East Coast - started to figure really hugely.”

Practice can be a creative endeavour

"I didn’t really focus on guitar very much at Berklee for various reasons. I was studying classical composition and biding my time because I didn’t know what else to do but, when I got out of Berklee, I started really practising the guitar.

"I just found practising boring, but figuring out that I could turn the whole thing into a creative endeavour was very, very interesting"

"I studied with a teacher, Charlie Banacos - who was a pianist - for a year in Boston after I got out of school, and he really taught me how to practise. He inspired me to think that if I was having some kind of problem or if I wanted something musically, then there were ways for me to come up with an exercise to develop what I wanted.

"That led me on to spending my 20s and 30s locked in a little room somewhere practising my guitar whereas, before that, practising was just something that was impossible for me. I just found it so boring, but figuring out that I could turn the whole thing into a creative endeavour was very, very interesting.”

It’s important to be where the action is

"When I was in Boston, I was just playing stupid gigs to make money because there was nothing creative happening in Boston per se. It’s too small a town for the number of schools that are there, so basically it is just a student town. It wasn’t really until I moved to New York years later that things changed.

"I’d made this record, which was never released, but I was using it as a demo to give to people for a while"

"Suddenly, I was playing with some of the people I’d always wanted to, and then I was playing with a lot of the people I always wanted to. I began working as a sideman in New York and got that whole part of the thing started.

"I’d made this record, which was never released, but I was using it as a demo to give to people for a while. I gave it to Steve Swallow, the bass player, and he gave it to Carla Bley. Then my friend Hiram Bullock was supposed to play with Carla one summer but he wasn’t able to and - because of that tape - I was asked to audition.

"Playing with Carla’s sextet was really my first professional gig. We were touring around Europe mostly, and through that I started meeting lots of other people, one of whom was Leni Stern. She had this regular gig down at The 55 Bar [Greenwich Village, New York] every Sunday night, and she asked me to play in the band.

"Just about every good bass player and drummer that was playing in New York at the time came through that band at one time or another, and that’s really how I established a whole bunch of friendships and connections that then led to a whole bunch of other work.”

Improvising onstage can be a truly amazing experience

"It’s hard to explain, but you just lose yourself. It’s this beautiful sort of super- heightened self-awareness, but then there’s also a complete abdication of self. You know, the stuff ’s just unfolding in real time like a planet being born or something, and you’re basically just right in the middle of this birth.

"At least in recent history, I think I’m definitely inclined towards the improvisational side"

"That energy that comes from improvisation - and the fact that improvisation allows that energy - is the true value of it to me. That’s a different thing to playing a song really well. I went and saw James Taylor the other night and they played You’ve Got A Friend and it was just incredible... you know, how many times has he played that now?

"But he knows how to access whatever he needs to access emotionally to make it every bit as great to hear him do it now as it was 40 years ago or whatever. That’s one kind of energy, and that’s fantastic, but that’s not improvising.

"In my mind, it’s compositional playing, but then there’s also improvisational playing and, for me, some combination of those two things is necessary. I would never want it to be all one or the other but, at least in recent history, I think I’m definitely inclined towards the improvisational side.”

Writing requires a different frame of mind

"For me, writing requires a different frame of mind than practising or playing. The whole bebop sensibility of writing, which then became the fusion sensibility of writing, is to write songs that are basically like improvising would be.

"It’s about being struck by an idea that you can then try and develop into something that’s more or less identifiable as a song"

"To do that, you compose in a way that is more congruent with how a band would play and practise and jam... but my stuff ’s not like that. It’s not really a transcription of a solo that everybody plays in unison or anything, so it requires a different awareness, or attitude, or frame of mind or something, to get to the place where that stuff is.

"It’s a real challenge because, with a guitar in your hand, you want to play it but it’s really not about that. It’s about being struck by an idea that you can then try and develop into something that’s more or less identifiable as a song.”

Older effects can give more tonal edge

"[With effects pedals] I guess I’m drawn to more sort of funky, organic-sounding stuff. That’s why I still use an old Boss Digital Delay [DD-3]. Even though just about every other delay that exists now is much cleaner and nicer and more beautiful, there’s just something kind of raunchy about it.

"For better or worse, I’m stuck with this raunchy sound. I’ve never been comfortable refining it the way that technology has allowed as the years have passed, and I don’t know why that is.

"I don’t know whether I’m just self-destructive, but there’s just something about when [the effect] gets too nice that it just doesn’t really lend itself to the kind of edginess that I’m looking for.”

Covering songs can give you inspiration

"The cover ideas [on Good Piranha/Bad Piranha] started a little while ago actually, when I was playing somewhat regularly again at The 55 Bar with my band, not every week like we used to, but often enough so that I was getting kind of bored with what I was doing.

"I just grabbed some songs from my records or from iTunes to see what the effect of it would be"

"I had the idea of almost arbitrarily choosing an artist and going through their stuff and coming up with eight songs of theirs that I thought we could improvise from, just taking themes from those songs and using them as vehicles to play from.

"For example, there was a Strokes night, a Joni Mitchell night, an Ice Cube night and a Thom Yorke night. I just grabbed some songs from my records or from iTunes with the idea a) to see if it were possible to make them work and whether we could improvise as we like to, and b) to see what the effect of it would be and whether it would be any different from when we improvised with my stuff. It was an interesting experiment and a few songs ended up sticking with the repertoire.”

Editing can be an essential skill on improv albums

"I’ve been doing this for a really long time, taking a live recording - even though it’s been recorded in the studio - and sifting through it looking for the magic. I’m really good at that now and I can instantly tell whether something has that feeling in it that I need or not. It’s really easy to make those choices.

"Sometimes there’s just a little bit more than the record can tolerate"

"I think [on Good Piranha/Bad Piranha] we only did about two takes of each track, although a few of them might have been three. It’s so exhausting to improvise like that because you can’t just go in and play for 12 hours. After you’ve done something twice, it’s kind of diminishing returns.

"With editing, one of the hard parts is sometimes just trying to fit it all on a record, because sometimes there’s just a little bit more than the record can tolerate... but the harder part is probably just figuring out how to edit the thing as a constructive process.

"You have 16 bars of something and you know you want to use it, but you’re not really sure how it’s going to work with the track. Where is it going to work? How do you get in and out of it? It is quite creative actually, and I started learning how to do it with the record Greenwich Mean in 1999.”

Every guitarist improvises to some extent

"[Improvisation] is like anything else. You just have to figure out how to make it sound good but you have to figure out how to make blues sound good, too, and how to make rock sound good, if that’s what you’re covering.

"If somebody’s out there playing a show every night that’s exactly the same, there’s still going to be some tiny thing they do differently"

"I shy away from calling things more difficult or higher or lower-level, because all that matters is that somebody is playing something that gives some kind of pleasure or relief or inspiration to somebody else, or at least to themselves. At that point, it doesn’t really matter what you do.

"I think everybody does improvise anyway. If somebody’s out there playing a show every night that’s exactly the same, there’s still going to be some tiny thing they do differently, a little moment of going for something or, ‘Let me try this’. It’s just some people bring that out and focus on it.”

Good Piranha/Bad Piranha is out now on Abstract Logix.