Songwriting legend Paul Williams looks back on a lifetime of hits

Robert Duvall first noticed that Paul Williams had a knack for this songwriting thing. It was 1965 and Williams had a bit part in the career-slump Marlon Brando starrer The Chase. He had started fooling around with the guitar, and one day before shooting a scene, he was doodling with some chords and singing some words that had popped into his head. Duvall walked by and stopped in his tracks.

“’What’s that?’ he asked me, recalls Williams. “I said, ‘Oh, just something I made up.’ And Duvall goes, ‘Come with me.’ He brought me to see Arthur Penn, the director, who liked it too. He ended up putting me in a little scene where I sing it.”

Williams had never thought about songwriting before – at 25, he was trying hard to make it as an actor, but his height (5’2”) was a problem for casting agents (he would lose out on The Monkees to another slight-of-stature actor, Davy Jones). But all at once, he remembers, “It was as if the universe was trying to tell me something: ‘You can do this. Music is the right path for you.’”

He recalls one of the first full songs he ever wrote, The Hunter, based on his one-and-only experience with a rifle: “I shot a deer, and as I looked at this dead animal on the ground, I just thought, ‘What have you done? You just lost your place in heaven based on this.’ So I wrote this song – it just came out of me – and if there was a craft in it or a level of intellect, it was way beyond anything that I thought I was capable of doing. The pay-off was the therapy I got from writing it. You focus on what’s going on in the center of your chest.”

Wiliams’ love for music of the 1930s, which then spread to Rodgers and Hart, Johnny Mercer and eventually to The Beatles, paired beautifully with another up-and-coming songwriter, Roger Nichols. “Sitting down and writing songs every day for several years with Roger became a great source of a place to really begin to understand the craft and form to the modern song at that time,” Williams says. “We were a really good match, and it didn’t take long for people to notice.”

The song placements started tentatively, but in 1970 the team of Nichols and Williams scored a smash with The Carpenters’ We’ve Only Just Begun (written initially for a bank commercial). And the hits kept coming: With Nichols, with other collaborators or on his own, Williams’ songs dominated AM radio throughout the ‘70s, with acts like Three Dog Night and Helen Reddy turning his compositions into gold and platinum. In 1976, Williams’ co-write with Barbra Streisand, Evergreen (Love Theme From A Star Is Born), hit the trifecta, earning a Grammy, a Golden Globe and an Oscar.

Surprisingly, Williams only called a hit once: Rainy Days And Mondays. "I remember going to the studio and hearing it for the time and thinking, ‘Oh, my God, that’s a smash,’ he says. “But a lot of times I was wrong. I have a whole bunch of songs in the drawer that nobody ever listened to all the way through that I was convinced were absolute monsters.”

By the end of the ‘70s, Williams’ growing addictions to alcohol and cocaine, coupled with what he calls “an addiction to attention,” caused him to bottom out. “I would say yes to everything,” he explains. “Films, TV shows – if there was a camera and a couch, I was there. Finally, I lost it and became a recluse. I went from sitting on Johnny Carson’s couch to hiding in my bedroom at three in the morning, looking out the window at the tree police, going, ‘OK, they’re out there…‘”

Williams pulled himself together, and now at 73 – and sober for 24 years – he’s experiencing a career renaissance that is nothing short of remarkable. He’s a certified drug rehabilitation counselor with a forthcoming book (Gratitude And Trust: Six Affirmations That Will Change Your Life, co-written with Tracey Jackson); he still performs; in 2009 he was elected as the president and chairman of the American Society of Composers, Authors and Publishers (ASCAP); and earlier this year, he picked up a Grammy for Album Of The Year for his unlikely collaboration with Daft Punk on their album Random Access Memories.

“When I think back to what’s worked and why it’s worked, it isn’t what I used to believe,” Williams explains. “I used to think that hits were based on intellect – ‘Oh, isn’t that clever?’ Wow, listen to that great lyric writing, and oh, isn’t that part clever?’ But clever doesn’t sell, intellect doesn’t sell – emotional content sells. Connecting with somebody. When I was writing from the center of my chest and something honest and authentic came out, even if it was embarrassing – that’s what works. Because that’s when listeners go, ‘Yeah, I know. I feel that too.’”

On the following pages, Williams looks back on 13 career-defining records.

Someday Man (1969)

“The Monkees had never recorded a song that wasn’t published by Screen Gems. To be an A&M writer with Roger Nichols and to land that record was huge.

“And interesting point: I tried out for The Monkees and was rejected. They already had Davey Jones; they had one little guy and he was the right guy. The band turned out to have exactly the right combination. I think Stephen Stills and I both tried out for The Monkees and were both rejected. Every time I’ve ever seen him, we both go, ‘Yeahhhh.’ [Laughs]

“It was just a thrill to have it recorded, although it was actually not a hit by them. There was a wonderful song by Mike Nesmith on the other side called Listen To The Band; it probably got as much play as Someday Man. But it was a great thrill, an amazing thrill, to have our name on a Monkees record. I loved the way that Davey sang it. It was a high point.”

We've Only Just Begun (1970)

“It had all the romantic beginnings of a bank commercial. Tony Asher, the great lyricist who wrote God Only Knows with Brian Wilson, had been asked to write a song for The Crocker Bank. Tony broke his hand while skiing and decided to pass on the job. He recommended Roger Nichols and me. It was, forgive me, our lucky break.

“The Crocker Bank contacted Roger and me about the commercial they wanted to do: a young couple getting married, they get a kid, they kiss at the wedding and the reception, and they drive off into the sunset. ‘There’s not going to be any sales pitch,’ they said. ‘It’s like a little movie’ – what we would now call a music video. And at the end, it was going to just say, ‘You’ve got a long way to go. We’d like to help you get there – The Crocker Bank.’

“I was like, ‘I don’t want to write a bank commercial. This is crap. I don’t want to do that – I’m a rock and roller. I may look like this little mush ball, but I’m an edgy street guy.' Which, of course, I wasn’t – a sentimental fellow then, a sentimental fellow now.

“But Roger said, ‘There’s a creative fee, so let’s do it.’ We wrote the song and wrote the commercial. The first two verses were for two little commercials; we put them together and finished the song, just in case anybody would record it. I was thinking, if anything, we’d get an album cut out of it.

“There was no way in the world that song was ever going to be a commercial hit; you couldn’t get further away from what was commercially happening at the time. When the Carpenters recorded it – when I sing this on stage, this is what I say about it: ‘And then an angel sang it.’ When that angel sang We’ve Only Just Begun, it literally changed our lives.”

Fill Your Heart (1971)

“Biff Rose and I wrote the song. He had started it – I think he had the first verse down, and I came in somewhere around ‘The dragons have been bled.’ I just started writing lyrics to it. He’s the first one who went to A&M Records and played them all the songs he’d written, including some that I’d written. They signed him, and then they wanted to see me as well. I wound up with a record deal.

“The song was recorded by Tiny Tim, a flipping gorgeous record produced by Richard Perry. But you know, it’s a classic example of what you think you want is not what you need. I didn’t really hunger for a Tiny Tim record. I really wanted a hardcore rock ‘n’ roll record. That’s the kind of writer I wanted to be, but it wasn’t who I was. I think I would have gone nuts to have somebody like David Bowie record it, but that wasn’t going to ever happen... Wrong!

“I’m not sure how Bowie heard the song, but my guess is – and what’s funny about the whole thing – I think he heard it from Tiny Tim’s recording – or Biff’s. By the time David did the Hunky Dory album, he was beginning to be a pretty big deal, and this was the first outside song he ever recorded. His talent is just immense. He’s a true renaissance man, an interesting guy on every level – film, acting and, obviously, writing and performing."

Rainy Days And Mondays (1971)

“My favorite line in the song was a fill line. I wanted to write a song about the blues, but I didn’t want to say anything about the blues. Chuck Kaye, the publisher, wanted us to show the song to the 5th Dimension’s producer, Bones Howe. I said, ‘The song’s not done,’ and Chuck said, ‘Yeah, yeah, you’ll finish in the car or whatever. Let’s go and show it… ‘ Just as a fill line, because I didn’t have a thing for the second verse, I added, ‘What I’ve got they used to call the blues.’

“Later on, it became my favorite line in the song. I think about that and go, ‘Yeah, you know what? Just get out of the way.’ The longer I do this, the more I realize that really good songwriting is about trying to put as little Paul Williams in the effort as possible. Just get out of the way and let it come.”

An Old Fashioned Love Song (1971)

“I had two big hits at the same time: Out In The Country by Three Dog Night and We’ve Only Just Begun by The Carpenters. When I started writing at A&M Records, Chuck Kaye, the head of publishing, was like, ‘Write with Roger. That’s it, you’re Roger’s lyricist. That’s gonna work for you.’ At the end of the day, Roger would go home – he had a girlfriend and a life – and I would just stay and write with anybody that wandered in the room. If nobody wandered in the room, I’d write songs by myself.

“I was never really encouraged to do either of those things until I wrote Old Fashioned Love Song alone, and then I wrote Family Of Man with a bass player friend of mine named Jack Conrad. All of a sudden Chuck was like, ‘You know what? Screw it. Write in any combination you want to – it all seems to be working.’ Old Fashioned Love Song, the story to that is, I went to pick up a girl to go out on a date, and as I was leaving the studio, I found out that I had a hit.

“I don’t know if it was Rainy Days And Mondays or what, but I walked into this girl’s apartment and said, ‘Well, the kid did it again with another old fashioned love song.’ And the girl went, ‘That’s cool, let’s go.’ I went, ‘Wait a minute...’ I went over and I sat down at her piano, and it’s the fastest that any song has ever come out of me. It was, like, a 20-minute period to write it. It just poured out of me, and I sent it to Richard Carpenter.

“I thought it was perfect for the Carpenters, but I don’t think he listened to it past the first verse. We sent it to Three Dog Night, and they reluctantly recorded it. All three of the songs I had with them were hits, and they reluctantly recorded all three.”

Waking Up Alone (1971)

“I mean, let’s be honest: I’ve made albums that even my family didn’t buy. [Laughs] I’m pretty proud of this song, though. It’s probably as close to literature as anything I’ve ever written because of the story it tells.

“The entire story changes in one line, and maybe if you were to ask me, ‘What’s the most effective one line you’ve ever written in a song?’ I would point to Waking Up Alone. The line is, ‘Oh your children, why the youngest looks just like you.’

“In the song, he’s been traveling – ‘I took my chances on a one-way ticket home’ – and he goes back to try to find the girl he left behind: ‘Thought the time for settling down had come at last/ Guess I hoped to find a future in my past.’ But he’s too late, and we know it in one line. ‘Oh your children, why the youngest looks just like you.’ It’s so sad to me, even now.

“You’re too late, pal. You should have gone back before. She’s got kids, she’s got a life. That’s also a song that falls into the ‘I-thought-somebody-might-have-cut-that-puppy-by-now' thing.”

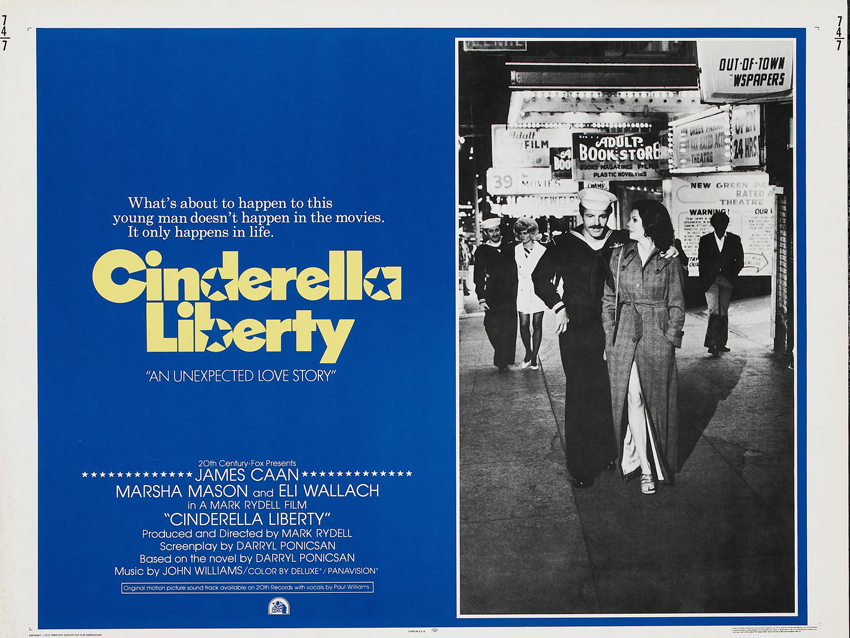

Wednesday Special (1973)

“It was my first motion picture effort, really, and the first thing that was noticed at all, thanks to John Williams being the co-writer. I loved the film. Everybody fell in love with Marsha Mason, including me, and I thought Jimmy Caan was amazing.

“I just listened to the lyrics, and it’s the most misogynistic lyric I’ve ever written in my life, and simply because I think it’s accurate for Caan's character. He comes from a world that is really like, ‘a good woman’s like a friendly bar, a Wednesday special or a good cigar.’ It’s interesting because as I look at it now, I go, ‘Well, what was I thinking?’ Well, yeah, that’s the world that Baggs [Caan] was coming out of, that sort of women-as-objects place – and then he falls in love.

“What I love about it, too, is the irony in it, the fact that ‘I’m just having a ball’ when he, Baggs, was as far from having a ball as you can get.”

Nice To Be Around (1973)

“It was the first one that I wrote for the film; it was just the piano version of the melody. I saw the movie, and I knew the story that I wanted to write about. I was also falling in love at the time with the woman that would become my first wife and the mother of my children – she’s still a great friend. I think that a lot of what I felt for Katie wound up in that song. I don’t think I’ve ever said that before. I should have said that long ago.

“It’s interesting: In the lyrics of that song, there’s a level of comfort. We’re talking about the beginnings of a relationship: ‘Such a simple way to start a love affair/ Should I jump right in and say how much I care/ Would you take me for a mad man or a simple-hearted clown.’ It describes that lovely, quiet way love can feel… Something about Nice To Be Around, it’s so understated. It’s not ‘You are my light, you are the fire in the midnight sky.' It’s, you know, ‘You’re nice to be around.’

“It’s like a precursor to ‘Love, soft as an easy chair.’ It brings it down into human proportions about this level of comfort and safety in a relationship that I haven’t felt before. I think that’s what in the song.”

The Hell Of It (1974)

“Talk about a film that was ignored at the time, but through the years it’s developed a large cult following. Now, all of this time later, it’s managed to come up with some gifts for me that I couldn’t have imagined.

“Right now, in fact, I’m writing a stage musical based on Pan’s Labyrinth with Guillermo del Toro and Gustavo Santaolalla. My relationship with Guillermo del Toro was born out of Phantom Of The Paradise. When he was a kid, he came to see me in Mexico City, and he brought the vinyl of the soundtrack to Phantom for me to sign. He was a huge fan of the film – he still is.

“It was the first time that I was totally immersed in a film. The Hell Of It was written for a funeral scene for Beef that we never shot. In the original script, Beef [Gerrit Graham] was killed in the shower. [Director] Brian De Palma and I talked about it, and then it became, ‘No, no, let’s have him killed on stage – and have the kids think it’s part of the show.’ That became, to me, the real theme of the movie, because this was at a time when people were watching news from Vietnam while they ate their TV dinners. The news, and the reality of the news, was becoming entertainment. The line between reality and fantasy was being blurred.

“It was the natural theme, I thought, to Phantom Of The Paradise: My favorite line I the film is, ‘An assassination? Live on coast-to-coast television? That’s entertainment!’ In the original script, right after Beef died, there was a funeral – they’ve dug the hole, the coffin is being lowered, and they’re singing this song. At the very end, a little girl runs in and jumps on the casket as it’s being lowered into the ground, and she starts tap dancing to audition. If you follow the cables from microphones around the coffin, they go all the way back to the hearse, which has a recording studio in it. Swan [Paul Williams] is recording the funeral.

“That very end of it was really a nod to Fellini films and to Nina Rota, where everybody was going to be in a circle around the coffin doing a little dance – very Nina Rota and very much a tip of the hat to Fellini, whom I love.”

You And Me Against The World (1974)

“Kenny Ascher was my piano player. We went to England to do a television show. I took my band, but the work permits never went through, so they couldn’t do the gig with me. Kenny and I were sitting around in my hotel suite with nothing to do. We were talking about the kind of music we loved, the music from the ‘30s or whatever.

“Just jokingly, I started talking about Harry Nilsson – we both loved Harry. You know, when I tried to tell Harry how much I loved him, he said, ‘Oh, that’s bullshit. Listen – this is great writing.’ And he played me all of these songs by Randy Newman. So Kenny went to the piano I had in my suite, and he started playing some chords and I sang.

"We did see a really short little song called Nilsson Sings Newman – ‘Do you love baby/ Do you love me not/ Let’s decide in the morning not now/ Oh you don’t like Schumann or Randy Newman/ Nilsson ain’t your cup of tea/ You think Van Heusen is a shirt worth choosin’/ But are you still undecided ‘bout me/ Whoa, whoa, do you love… ‘

"It was this short little song, but at the end of it, Kenny looked at me and said, “You know, it’d be nice to do something really different like,’ and he went, ‘Pom, pom, pom, pom, pom, pom, pom, di, du, di, du/ Pom, pa, da, da, da, da, da, da’ – played the intro and he looked at me, and I went, ‘You and me against the world.’ And he played a chord again.

“I sang, ‘Sometimes it feels like you and me against the world.’ And that’s how it began. It was the first of the three songs we wrote; one of them a joke, and one of them serious. We played it for Liza Minelli at first, and she was going to record it. By the time it got around for her to do it, it had been sent to Helen Reddy, who had recorded a bunch of my songs before, but they were always B-sides. I had the B-side to I Am Woman, and I had the B-side of Delta Dawn. But this she put out as a single.

“The best part of that song today is that I get a heart payment for it. I get people coming up to me and saying, ‘You know my mom was a single mom, and that song was really important to us.'”

Evergreen (Love Theme From A Star Is Born) (1976)

“What a nice surprise. I sat down with Barbra to talk about writing the songs for A Star Is Born. Very shyly, she said, ‘Do you think you could do anything with this?’ She was just learning to play the guitar, so she took a guitar out and started to sing this lovely melody, all the time struggling to find some chords: “Da, da, da, da, da, da…’ She looks for the next chord – ‘Baa, da, da, di, da, da…’ Now she really looks for this next chord – ‘Da, da, da, di, da, da…’ I went, ‘Oh, my God, it’s gorgeous. There’s your love theme.’

“So I wrote the love theme, but the original first two lines were reversed, I wrote, ‘Love fresh as the morning air/ Love soft as an easy chair.’ An easy chair does not sing well there, so I asked her, ‘How do you feel about flipping those first two lines? Love soft as an easy chair/ Love fresh as the morning air.’ I said, ‘They’ll probably laugh us out of town for opening a song with a line about an easy chair.’ But I thought it worked.”

“Most of the songs for the movie I wrote with Kenny Ascher, and the song that just killed me in the movie – I mean, I’m so proud of all of them, and I’m thrilled that Barbra and I won the Oscar and the Grammy and the Golden Globe – but the song With One More Look At You, I thought it would have a life and would have much greater impact than it did. Barbra’s performance of the song is brilliant – one long take in close-up and she nailed it. I remember thinking, ‘There’s a song that’s going to get covered to death.’ I was wrong. It hasn’t. You never know.

"When I met my wife, Marianna, 14 years ago, she said, ‘You wrote my second favorite song.’ I went, “Well, thank you very much. What’s your first favorite song?’ She said, ‘What Are You Doing The Rest Of Your Life’ by Marilyn Bergman. But One More Look At You was her second favorite song. I’ll take that.”

The Rainbow Connection (1979)

“I’d been over to do The Muppet Show with Jim Henson, and we got along great. He said, ‘We’re going to do a thing for HBO called Emmet Otter’s Jug-Band Christmas – would you write the songs for it?’ I wrote the songs for that, words and music; we got along great, and he then came to me and said, ‘Would you write the songs for The Muppet Movie?’ I said, ‘Yeah, but I don’t want to do it alone. This is a project that I’d love to have a great composer involved.'

Kenny Ascher and I were friends and had written You And Me Against The World together, as well as the songs for A Star Is Born, so I brought him in. We sat down with Jerry Juhl, the screenwriter, and Jim Henson, and we went through what the story would be about.

“With the first song we discover Kermit in the swamp, so we needed his ‘I am’ song, where we find out who he is and what he’s about. Kenny and I thought about it, and what we wanted to do was try to write something that would have the same impact on the listener as When You Wish Upon A Star in Pinocchio. When Jiminy Cricket takes off his hat, climbs up onto the window, looks at the night sky and sings, ‘When you wish upon a star… ’ – if that doesn’t touch you, there’s something wrong with you. You’re missing something in the center of your chest.

“We thought, “OK, Kermit is out there in the swamp. He’s got what? He’s got water, he’s got air, he’s got light, so he’s got rainbows.’ We started it out, but we were actually painting ourselves into an awful corner with the first verse: ‘Why are there so many songs about rainbows/ And what’s on the other side/ Rainbows are visions/ But only illusions/ And rainbows have nothing to hide.’ ‘Wow, now what are we going to do? We just took all the magic out of rainbows.’

“We let Kermit state the negative and then answer with a positive: 'So we’ve been told/ And some choose to believe it/ I know they’re wrong, wait and see.’ What we did in the first verse was to see the positive Kermit against the world that is real and maybe even negative. ‘Someday we’ll find it/ The rainbow connection/ The lovers, the dreamers, the me.’ It put us on a nice path to a new way of thinking, a higher frog consciousness, and it also added to Kermit being everyman – or rather, ‘everyfrog’...[Laughs] He’s the little guy with a positive attitude who's not going to let all the evil in the world get him down.”

Touch (2013)

“I’d just done a tour with Melissa Manchester. Peter Franco was mixing sound, and once we were done he went to work with Daft Punk. I don’t know if he was working on the film they scored, Tron, but when they needed a piano overdub for something, Peter suggested Chris Caswell. Chris – I call him Kaz – has played piano for me for decades.

"Kaz went in and played on the stuff. Suddenly, he hears the Daft Punk guys talking about Paul Williams – they were wondering how to get in touch with me. Peter and Kaz both turned around and went, ‘We just got off the road with him. Do you want to call him? You want an email address?’

“They sent me an email and then came to see me. They gave me a melody and asked if I’d write something. Actually, the first thing that Thomas [Bangalter] gave me was a book on life after death – people who had died and been brought back to life, what they’d seen. He said, ‘I don’t know what it has to do with it, but I want you to read this.’ I went, ‘Oh, my God, I read that book! I must have read it 10 years ago.’

“We didn’t know if we were writing about somebody that’s coming out a coma or somebody who’s died and come back to life, or if we’re writing about somebody who’s cryogenically been induced into a coma for space travel and has been brought back to life. It’s obviously about an awakening of some kind.

“They gave me the first melody, I wrote the lyrics to that, and then they gave me the one that became Beyond. I wrote the lyrics to Beyond, and then they asked me if I would sing Touch. This was over a long period. I wrote the first one – they went away and came back. I wrote the second one – they went away, came back with tracks and had me sing Touch.

“Then they went away and came back and played the album for me, and I just went, ‘This is brilliant. This is just… you guys are beyond amazing.’ What impresses me – well, there’s the anonymity thing, but also the fact that they sailed into some deeper emotional waters. Before we won the Album Of The Year, they asked me if I would accept the award if we did, in fact, win.

“You know, they could have made one more EDM record. Because they are at the very headwaters of EDM, they could have done something very much down the center of the pike and had a sure-fire, multimillion-selling album by kind of recreating what they had done before. What they did was say, ‘Now, let’s take a look at what influences us and try to do something new with that.’ All of a sudden, I’m 73 years old and standing on stage, and I'm thanking the Academy for Album Of The Year.

“It’s just an amazing gift at this time of my life. With all the things that are going on, from being 24 years sober to standing with a new Grammy – now three Grammys instead of two on my piano – and my third term as president of ASCAP, fighting for other music creators’ rights, I just go, ‘Paul Williams, you’re the luckiest little guy in the world.’”

Joe is a freelance journalist who has, over the past few decades, interviewed hundreds of guitarists for Guitar World, Guitar Player, MusicRadar and Classic Rock. He is also a former editor of Guitar World, contributing writer for Guitar Aficionado and VP of A&R for Island Records. He’s an enthusiastic guitarist, but he’s nowhere near the likes of the people he interviews. Surprisingly, his skills are more suited to the drums. If you need a drummer for your Beatles tribute band, look him up.