Larry Carlton on Steely Dan, Joni Mitchell and solo secrets

In-depth with 'Mr 335', the solo and session legend

Introduction

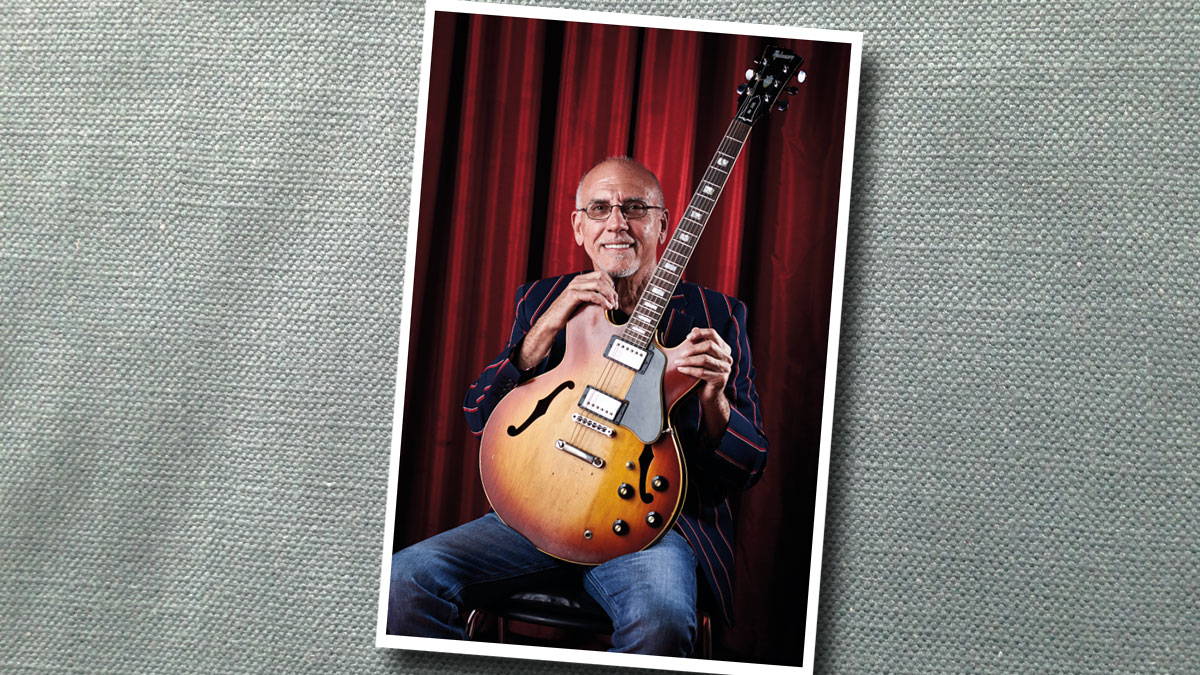

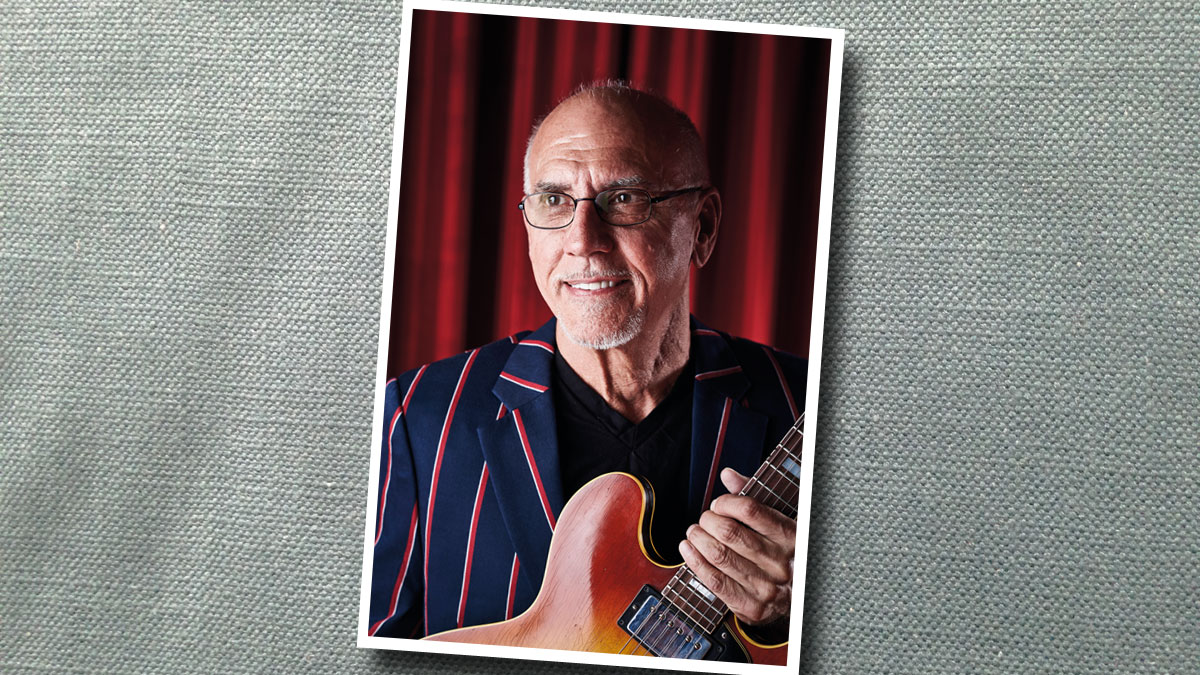

Larry Carlton’s fretwork has been the magic ingredient of so many great albums, it’s ridiculous. From his graceful, jazzy playing on Joni Mitchell’s Hejira to the ecstatic solos on Steely Dan’s The Royal Scam, he is the heavyweight champ of ES-335 artistry.

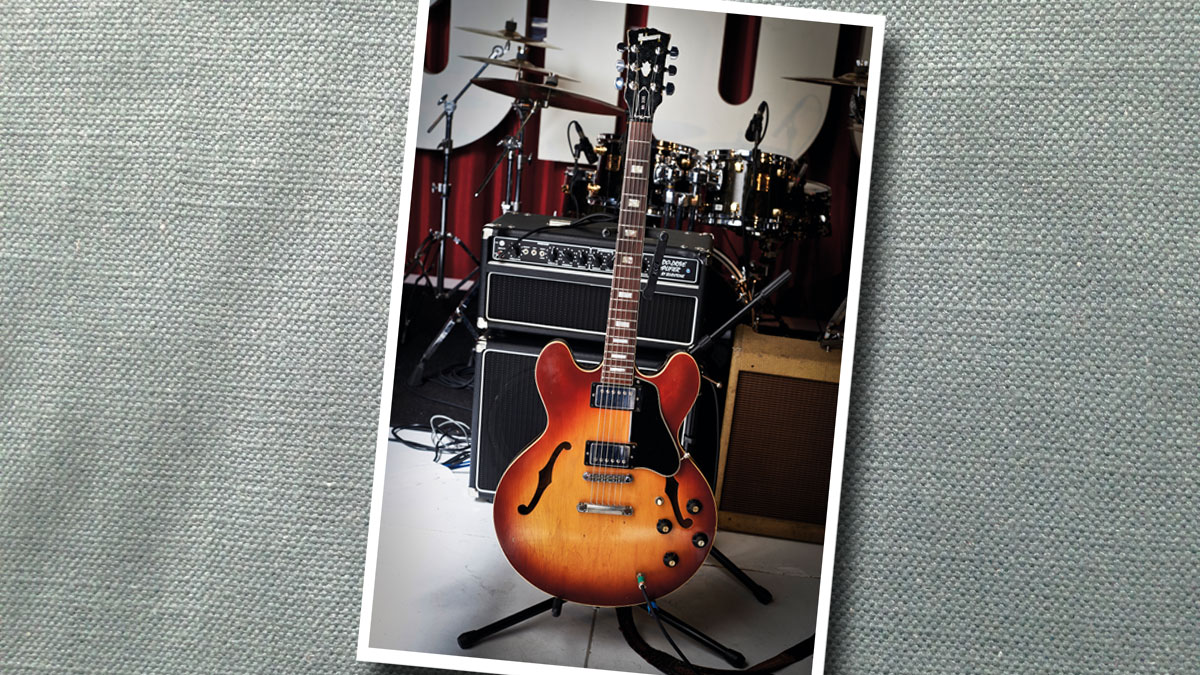

The weathered ’69 ES-335 sitting on its stand on an empty stage this afternoon has certainly earned its keep over the years.

Its owner, Larry Carlton, has played this guitar to such dazzling effect, on so many albums, that every hairline check in the lacquer of its headstock might stand for a hit. From Michael Jackson to Joni Mitchell, Larry Carlton’s playing has added grace and sophistication to career-apex albums by some of rock’s greatest artists.

"I learned over the years that you play something and you leave a space"

Today, however, he’s touring his own material. Carlton has recorded over 30 solo albums, which gives him the luxury of wandering at leisure through his sizeable back catalogue, changing gears between stately blues and energetic fusion as the mood takes him.

“I’m playing songs that I have been doing for the last five or six years, kind of a broad cross-section of material,” he says. “Some of it is very jazz, some of it is very blues and some of it is fusion. This is my third or fourth tour with these particular musicians: Klaus Fischer on bass, Jesse Milliner on keyboards and Hardy Fischötter on drums.”

During soundcheck, we get a taste of what the quartet is capable of. Together, the band combines finesse with heavyweight chops and Larry’s playing against their backing is characteristically unhurried and tasteful, with easy flourishes of invention that seem to just flow out of the amp. Interesting to notice, too, that the lower fingers of his right hand are in play almost as often as the pick.

“As a jazz-influenced player, my comping is done commonly with the pick and two fingers,” Carlton says. “And then, for just a different tone and a different attitude, sometimes I’ll just not use the pick when I’m playing my blues lines, so I can snap the string a little harder. Just gives me a different attack.”

A big part of great playing, he continues, is in treating the space between licks as an opportunity, not a chasm that might swallow you up if you don’t fill it with notes.

“I learned over the years that you play something and you leave a space,” he says. “Well, a number of things can happen in the space. One, you can get another idea. Two, somebody else in the band might play something in that space that inspires you. Or somebody in the band plays something that is so appropriate for what you just played. Or you are going to play what you just played again except barely vary it. The space is an opportunity for something to happen.”

Harmony Lessons

A particular hallmark of Carlton’s playing is the easy way he marries a jazz guitarist’s ear for harmony with the gutsy phrasing of blues and rock, a style he developed - perhaps surprisingly - without formal lessons.

“For me, it started by learning standards,” he recalls. “I remember that when I would learn a four-bar phrase from a Joe Pass record, I’d then go back and learn the chords that were happening underneath it, not just the solo. Then I had the opportunity to analyse it in my head: why could he play those notes against that chord? I think it’s important that once you learn the solo, learn the chords, then think about why that could happen.”

"It’s really about being a musician, not being a ‘guitar player’"

In the past, Larry has spoken about building solos not around scales but simple clusters of notes that can be played, then re-stated and mutated up and down the fretboard. Does he still approach improvisation in that way?

“That’s the motif approach of making a small statement and then developing that statement,” he says. “It always shows up in my solos. I haven’t abandoned it but I am not really aware of it. To me, that is just the musicality that comes out of me. Play something and wait a second. If nothing else comes, imitate what you just did. It is a patience thing.”

Guitar players, we suggest, sometimes have trouble staying cool and pacing themselves in solos. Any tips? “Well, it’s really about being a musician, not being a ‘guitar player’,” he observes. “For example, sax players have to take a breath. They can’t just run on, sentence after sentence, like we can on a guitar. So take a breath.”

The patient approach also served him well as a session player, he adds. “There are a lot of guitar players that play along on the first run-through of a track, because they want to make sure that they are going to find something, so they can be heard. But my approach was always: don’t even play on the first run, through, just listen to the song. We have time.”

Charlemagne champion

One of Carlton’s cardinal virtues as a player is that ability to size up a track and then produce improvised guitar parts that stand the test of decades of listening, most notably on sessions with Steely Dan and Joni Mitchell.

His two ecstatic solos on the former’s Kid Charlemagne, a kind of musical Breaking Bad that tells the story of illicit LSD factories in 60s San Francisco, is seen by some as the high-water mark of Carlton’s soloing on any record.

“I had prepared the chord charts and we had already cut the track,” Carlton recalls of the session. “I don’t know if it was weeks before or months before,” Carlton recalls.

"I decided to take my little Tweed Deluxe with my 335 and that became my lead sound with Steely Dan"

“I really don’t remember but then it was time. They had the tracks in a place that they now wanted to put the lead guitar on. I am sure there was vocal and something. I can’t remember why but I decided to take my little Tweed Deluxe with my 335 and that became my lead sound with Steely Dan.

“Once we found a tone that we all agreed on, Donald Fagen and Walter Becker would say, ‘Yes, that’s cool,’ then really it was just a case of, ‘You want to try one?’ And they would hit the red button and it’d maybe be, ‘How you doing?’ and I’d say, ‘Yes, let’s try it again.’ Then all of a sudden some magic starts happening. Very patient, there were no suggestions of licks or anything like that.”

The song’s first solo is a masterpiece of coolly poised improvisation. By contrast, the outro solo is almost recklessly exuberant, with the 335 singing all the way to the fade. Unsurprisingly, the solos were waxed on separate takes.

“I am pretty sure that I made the solo section in two parts,” Carlton recalls. “It seemed like I was flying along pretty good and then something happened and we stop and he says, ‘Pick it up right there,’ I continued on and finished the solo and played through the ending maybe, but there are vocals that come in from there.”

On other standout sessions from The Royal Scam, however, a little discussion with Donald Fagen and Walter Becker helped get round awkward spots, notably on Don’t Take Me Alive, a hard-boiled siege thriller in the form of song, which starts with a searing solo from Larry Carlton.

Launching into full flight right on the first beat wasn’t working out right, Carlton remembers, and it was Donald Fagen who suggested the jagged, drawn-out chord that precedes the song.

“There was no chord in front of the beginning of the song, nothing. Just ‘wham’. I don’t know what else we tried, but Donald was the one who finally just said, ‘Why don’t we just put a big chord in front of it?’ It was that simple. I went out into the room where my amp was and stood in front of it and tweaked until there was [the right tone] and then I did four or five or six of those chords to where everything rang. They adjusted the limiter and everything so it really sat like they wanted it to. But Donald was right.”

Carlton’s playing with Joni Mitchell, on mid-70s classics such as The Hissing Of Summer Lawns and Hejira, took place against the more mysterious backdrop of Mitchell’s enigmatic open tunings. He recalls that the same approach applied.

“For her to use those tunings... was like playing with a jazz player who’s using different voicings. I still hear what the chord is - even though it sounds unique and beautiful the way she tuned her guitar. But, no, it was not a special challenge.

“She would just have me play. And I remember that on the album Hejira that had Strange Boy on it - that album with me and Jaco [Pastorius] - she already had her guitars recorded and at least a rough vocal. And I was in the studio by myself and she said ‘Just play, Larry.’ And so I would play three, four, five approaches and then she later would choose the goodies that she liked. So it was very free.”

Tone On Tour

The tone of many of Carlton’s classic 70s cuts may have leapt from the low-wattage, cathode-biased heart of a 50s Tweed Deluxe, but his stage rig for the current tour is a far more gutsy setup, built around a Bludotone Bludo-Drive 100/50 head and closed-back cab with a single EVM12L 12-inch speaker.

“I have a Bludotone that I leave in London and for European tours I also bring a small pedalboard with a reverb, a delay, a volume pedal and a wah-wah [see picture].

“There are a few countries, though, where I can’t take my amplifier because the airplanes are too small so I get stuck with a hired backline. I am not a fan of Twin Reverbs for my playing, but I can usually have a nice enjoyable evening with a Fender Blues Deluxe with reverb as backline, though. It lets me respond somewhat as I like to.”

"I seem to always be looking for the same tone - that sweet, singing distortion that’s not so driven that it’s not musical"

Larry Carlton is one of those players whose tone is always at a simmering half- crunch, right on the cusp of a full-throated wail. He says he dials in the preamp of the Bludo-Drive carefully to keep himself in the right zone to suit the 335.

“The front end is really important to me. I have found with both my Dumble and with the Bludotone - and by the way, my Bludotone is an exact clone of my Dumble - my preamp volume is usually about four, then my tone controls and midrange are down a little bit.

“That amp sounds best set at four going in and four coming out. But it is too loud for me now: I want Brandon Montgomery who makes the amps to get it so I am happy with it on [a master volume of ] two. Because the amp wants to breathe at four but it doesn’t want to breathe quite as much at two. But four is just getting too loud for me!”

Another key element of Carlton’s tone is having the perceived level remain the same when switching between his clean and lead tones, and his amps are customised to make this easier to achieve.

“I don’t like the level to change. That was an adjustment with Dumble and then with Brandon for the Bludotone. They have a little green button that kicks in the preamp.

“Originally, when you kicked that in there was like a two or three dB boost. But I don’t want to be louder, I like where I am at right now, but I want that different tone. So that has been adjusted for me. The volume is perceived to be the same but the tone has been slightly altered, a little more aggressive.”

Also on hand for an additional layer of gain, or an alternative to the overdrive voicing of hired backline, is the Tanabe Zenkudo Overdrive pedal on his touring ’board.

“It seems to work really good with a 335. I tried the Zen Drive but for my ear, it was totally inappropriate playing the 335 through it. I seem to always be looking for the same tone - that sweet, singing distortion that’s not so driven that it’s not musical,” he concludes.

335, Alive And Well

One thing that hasn’t changed a lot, of course, is the hard-toured ’69 ES-335 that Larry has used on most of his recordings. As it hasn’t broken, Larry hasn’t fixed it - beyond a switch to a different bridge and Schaller machineheads.

“Obviously, over the last 35 years or something it’s had a number of fret jobs or level and dress,” Carlton says.

"There is going to be a season, I think, in every guitarist’s progress where it is just fun to play fast because you can. But it shouldn’t be the end result"

“It came with normal Gibson frets and over the years, I’ve gone through the process of trying Dunlop frets that were very big and very high but now I’ve switched back to whatever the normal Gibson fretwire is for a 335. Other than that, it has that graphite nut that we put on back in the 80s and it originally came with the trapeze tailpiece. But I don’t know that I’ve ever changed the pickups.”

As showtime draws near, we wind things up talking about the high standard of technical ability among players coming up not through gig venues but on YouTube and elsewhere. What does Carlton, whose playing blends feel with technical elan beautifully, think about the outrageous displays of technique that even a casual browse of the internet can yield?

“I think it should just be part of the process but not the end result,” he reflects. “As a young musician, and you could be 35 years old and only playing the guitar 15 years... to me, you are still a young musician. There is going to be a season, I think, in every guitarist’s progress where it is just fun to play fast because you can. But it shouldn’t be, in my opinion, the end result.”

Better to have it and not need it? “It was fun,” he concedes, with a grin. “To get to where you could play really fast. It was fun.”

Larry Carlton is currently on a worldwide tour and will return to play numerous dates in Europe from this October. See his website www.larrycarlton.com for details.

Jamie Dickson is Editor-in-Chief of Guitarist magazine, Britain's best-selling and longest-running monthly for guitar players. He started his career at the Daily Telegraph in London, where his first assignment was interviewing blue-eyed soul legend Robert Palmer, going on to become a full-time author on music, writing for benchmark references such as 1001 Albums You Must Hear Before You Die and Dorling Kindersley's How To Play Guitar Step By Step. He joined Guitarist in 2011 and since then it has been his privilege to interview everyone from B.B. King to St. Vincent for Guitarist's readers, while sharing insights into scores of historic guitars, from Rory Gallagher's '61 Strat to the first Martin D-28 ever made.