Jackson Browne talks guitars, production and new album Standing In The Breach

You notice something very striking about Jackson Browne when listening to his new album, Standing In The Breach. Among the record's myriad rich and sublime attributes – the dreamy bed of Byrds-like guitars on The Birds Of St. Marks, the spellbinding transposition to song of an unpublished Woody Guthrie letter, along with Browne's engrossing examinations of human bonds and social-political concerns – there's the singer's sweet and soulful voice: It's as pure and present as it's ever been, an instrument that is, it would seem, ageless.

Browne laughs in almost an "aw, shucks" manner when I compliment him on his singing and how, unlike so many other veteran performers his age (he turns 66 on October 6), it doesn't sound as if he's making any noticeable allowances for changes in his vocal range. "The truth is, I never really liked my singing very much, especially in the beginning," he says. "Then, at a certain point, I got comfortable with the way I sang because it seemed to work, especially live. I’d realize how not to do stuff that doesn’t work. I’m still settling for a kind of limited palate."

The singer does admit to "studying" his voice in recent years, even going to see what he calls a "vocal repairman." "I just said, 'Fuck it, I'm going to figure out how to make some of the sounds I want," he says. And on the new record, he even made some changes to how he tracked songs, focusing on one number at a time and sticking with it until he was happy with his vocal performance. "It worked out well, singing one song until I was finished rather than trying to sing them all at once," he says. "It also allowed me to get a different sound on certain vocal so that they wouldn't be engulfed by the tracks.’ Each vocal would hold its own."

Browne recorded Standing In The Breach at his own Santa Monica-based facility, Groove Masters, with a group of players he's worked with for years – among them, guitarists Greg Leisz, Val McCallum and Mark Goldenberg; drummers Jim Keltner and Mauricio Lewak; bassists Bob Glaub and Kevin McKormick – as well as some notable guests like keyboardist Benmont Tench, drummer Pete Thomas, bassist Tal Wilkenfeld, singer-songwriter Jonathan Wilson and Dawes frontman Taylor Goldsmith.

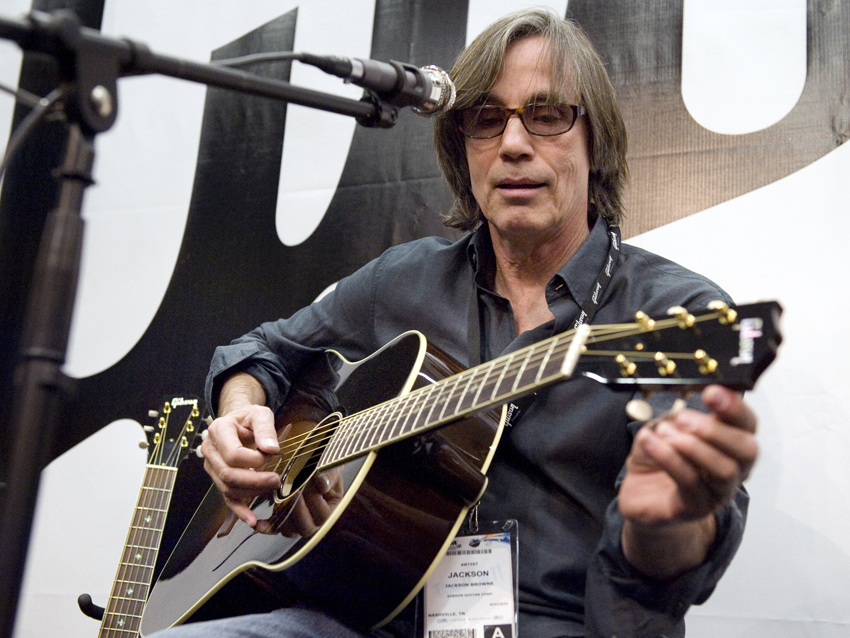

Browne sat down with MusicRadar recently to talk about recording the new album, the guitars he used, his own style of fingerpicking, politics in music, producing other artists and his recollections of the late Stevie Ray Vaughan. (Jackson Browne's Standing In The Breach, due out October 7, can be pre-ordered at iTunes, Amazon and at this link.)

I understand the record didn't come together like to many others – you know, you go in to record everything all at one time.

“It sort of fell together based on the kind of fun I've been having sitting in with The Watkins Family Hour, with Sean and Sara Watkins, a little while ago, along with Jon and his band. A sort of jammy, friendly kind of arrangement is at the heart of it. That’s what we were going for in the studio. I've been heading in that direction, but in this case, I culled various different people rather than having one band playing on every song.”

You do mix it up with quite a few folks. There's some newer artists – Tal Wilkenfeld, Jonathan Wilson, Taylor Goldsmith – and some people you’ve worked with quite some time.

“Yeah, there's a chemistry that’s pretty interesting. What goes on with Val McCallum in my songs, is sort of at the heart of the album. But also, there’s Greg Leisz, who Val loves to play with, and whom I've been really running into a lot. We've all become good friends. The combination of those two guys sort of knits the whole thing together. Otherwise, it was a matter of trying to call the right guys for the right job.”

What are your feelings about the role of the album in 2014? A lot of artists are putting all of their efforts into singles. And now we have U2 giving their album away for free –

[Laughs] “I knew we were heading for that.”

Do you feel as though you were part of the “good old days,” when artists made albums, and albums were revered by record buyers?

“Yeah, of course, it’s obvious that things were a little bit more economically satisfying back then. Albums sold more, but I don’t know if that meant I produced better music. Everybody was so well paid during the ‘70s and ‘80s. There's that famous remark by Bono – ‘the undernourished and the overpaid.’ Basically, if you’re young and you make a successful record, you get sort of overpaid. And the money becomes an obstacle because you’re trying to recreate that success.

“You’re trying to sustain that, and the people around you are, too. Whether it’s business managers or a record company, or just your friends, there's an expectation that, above all, you have to sustain this level of economic success – and that doesn’t always serve the music. In my own case, I went from playing concert halls to playing arenas, and one of the things that sort of fell by the wayside for several years was the intimacy of playing acoustic songs. The emphasis was in filling that basketball arena. It leaks into everything.

“I've got to say, I think that music is alive and well, and there are great writers and great players popping up everywhere. It’s just not going to be what it was before. It may be that young bands now aren't dreaming of buying their first jet, which was sort of a shocking development in the ‘80s, when somebody from Journey said, ‘Yeah, I always dreamed of having my own plane.’ Really? I mean, they’re really great, but you can see that it’s fine for music to not pay so well.

“In my own case, I always wanted to make as much money as possible because I could pay more to the people who played with me. It becomes a matter of a quest to make sure that you’re traveling well and everybody gets paid well – that sort of thing.”

On The Birds Of St. Marks

So, ultimately, it is making for better music.

“Yeah, it can. Although, I’ve got to say that I always took a lot of time between records; I wasn’t really trying to maximize. I didn’t tour for three years after Running On Empty. I toured while we were putting it out, and it became the biggest record I’d ever made, but it also coincided with my son starting school. He was five, and I just said I’m not going to go tour for the next few years, and I just spent time writing. It actually seemed about right. It seemed normal in the context of what happens when you’re trying to make your initial records anyway. There's a lot of waiting and getting things how you want them.”

Your new song The Birds of St. Marks isn’t really new at all – you wrote it in the ‘60s. How does a something like that sit around for so long?

[Laughs] “Because it took that long to figure out how to play it. For a while, I kind of forgot about it. When I wrote it, I imagined it like a Byrds song, for the simple fact that I wrote it for Nico, and she was a big fan of Roger McGuinn. So it’s kind of a Byrds song, but it’s also got birds in it.

“If you hear the old demo, you hear the [hums] – that guitar sound is built into it. But if you play it on the acoustic guitar, it doesn’t sound anything like The Byrds. It just never seemed like it was done; it never seemed finished. Then, on top of it, it’s kind of a young song, so there was a period of time when I thought, ‘Oh, this really does have to be rewritten.’

“Finally, I stopped waiting for The Byrds to reunite so they could play it [laughs], and I got old enough to be happy to just sing one of my earlier songs and leave it alone. Don’t try to rehabilitate it as if there was anything wrong with it in the first place. And finally, when I realized that Greg Leisz could play it, I thought it might be cool to get close to a Byrds song.

“It’s not exactly like a Byrds song – it’s got those trappings. I talked to [David] Crosby about harmonies. He's been singing on my records since my first one, but he would always sing multiple parts. What he told me about The Byrds – and this is something that people probably forget – is that they were always two-part. It just sounded like more people singing because one of those voices was sometimes doubled. In a few instances, there was a third part, and on this song, on one line, we do sing three parts. It’s a matter of trying to cultivate a sound and a feeling that’s pretty much of the time that it was written in.”

You Know The Night

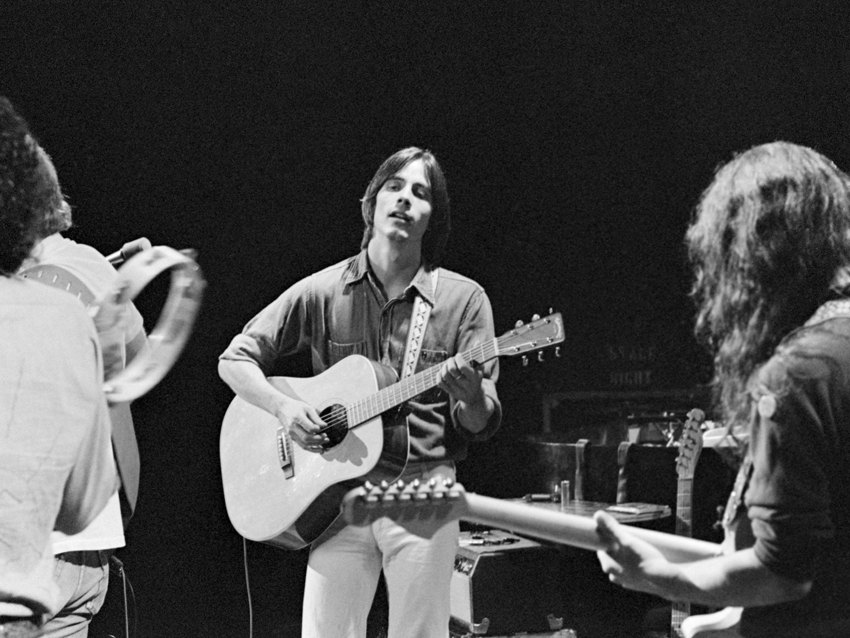

Above photo: Jackson Browne and his live band (from left) Jeffrey Young, Browne, Bob Glaub, Mauricio Lewak, Greg Leisz and Val McCallum

You include You Know The Night on the new record. Several years ago, you did that track – a full 15 minutes of it then – for the the Woody Guthrie celebration album, Note Of Hope.

“Yeah, exactly. It was written for that album. Rob Wasserman had a project with the Guthrie family in which he had access to their archives and their songs, the unfinished songs. In this case, it wasn’t really a song; it was a letter. That is, it was a letter until the song was written. Maybe it’s a good thing that it wasn’t a song. We just sort of printed it out, and I edited it a little bit. I couldn’t take very much out because it was such an incredible autobiographical account of not only Woody meeting his wife but also why they were attracted to each other – what they valued in their lives at the time.

“I just thought, ‘This stuff’s all got to be there’ – but there was no pressure to make it something else. Rob was great. He said, ‘Sure, 15 minutes is fine.’ The record company afterwards said, ‘Well, maybe we could, if we want to get it played on any radio station, maybe it would be a good idea to have a single edit.’ Not that it was going to be a big single, either. What happened, really, is that the song continued to develop. The music got a little tighter, and I found some chords that would work for the chorus – it wasn’t just going back and forth between two chords the whole song.

The version on your new album is great. Like the 15-minute reading, it’s like a meditation, almost. I love that repeated line “and you feel like the devil is scratching your heel.” What a lyric to have in a love song or love letter.

“Well, that’s just it. It’s that mischievous part of Woody Guthrie. It’s the lusty kind of hard-traveling guy that he was. That stuff just poured out of him. To say, like, ‘the angels were curling her hair,’ and ‘the devil was scratching my heel,’ it’s like being caught between all the impulses. He had that goodness, but at the same he had kind of a mischievous, pleasure-loving nature as well. I think that the ‘devil scratching the heel’ part is really great because it’s sort of like the balance to his really very noble impulses. That was one of the lines that made me decide to do it.

“And in the end, for him to say to her, ‘All of your hopes and your plans for the good of the people.’ Do you ever hear that in a pop song? Hopes for the greater good for everybody is really at the heart of the anti-war movement, the civil rights movement, the labor movement. It’s about wanting the good. It’s very easy to put people off with intentions that are too good.”

On fingerpicking

The song Which Side? features some terrific lap steel playing by Greg. You always had a great ear for brilliant guitarists – lap steel players, especially.

“I developed that by getting to play with David Lindley. What happened right away on the first record I made with him, which is my second album, was that I saw how I tended to pick the track that was his best offering. By saying that, I mean, he doesn’t play the same thing each time. When we'd have a track that he played really well, the rest of the song would sort of develop around that.

“David’s playing and the chemistry that happens with other guitarists is really at the heart of the way I've made records. It’s not always the case because some songs are written on piano and some are written because of how I play guitar by myself. Actually, on this record, I tried really hard to integrate my guitar playing into the record. It’s a limited part, but I wanted to be heard, a sort of reverse fingerpicking. It’s the same thing on Leaving Winslow as it is on some earlier songs of mine like Never Stop. It’s a rhythmic thing, and it’s very easy to cover that up. As a matter of fact, when we first played the song, we found that the Telecaster could totally command the arrangement, so we took away some other stuff away and developed it so that could be heard.”

You’ve always been a great fingerpicker, by the way. Where did you develop your style?

[Laughs] “Nobody’s ever asked me that before! I mean, when I started playing guitar… Maybe the first guitar piece I really cared about was Don’t Think Twice – Bob Dylan’s way of playing. But it just didn’t come out the way his did. I can kind of play it like him. I don’t even think I play it in the same key. I would hang around the clubs and the guitar stores, and I noticed there were certain pieces you’d try to learn because everybody seemed to be able to play them. Cocaine Blues, Dave Van Ronk’s version – that’s where I got that reverse thumb thing.

“He played it backwards, although I can’t really play it the way he played it. The same with Mississippi John Hurt – he might go to that, like, on C. C. Rider. [Hums guitar part.] I always liked that, and I would always stick it into other songs. When it goes to the five-chord, I just turn it around so I get to do that for a moment. I started fingerpicking when I was about 15 or 16, I guess. I gave lessons to people in my town, home lessons and stuff. I kind of had to look at what I was doing in order to get other people to do it.

“If I may say so, it’s really a cool way of playing; the thumb will keep you going. You don’t have to play a complicated pattern on top of everything; you can just play whole notes if you want – it just marks the time while you play other things. When I play Warren Zevon’s Don’t Let Us Get Sick, I’m adopting it to the way I play because I actually can’t play it the way he did, nor can I play anything on piano the way he did. It’s just not part of my skill set; he was way beyond me. But whatever I play, I try to do it in a way that works for the song. That’s the main thing. They’re not really flashy ways of fingerpicking or piano playing, but they work to support the song.”

On politics in music

What was it like putting Tal Wilkenfeld and Jim Keltner together on the song If I Could Be Anywhere?

“It was a complete and utter joy. In fact, that was the session they met on, and since then they’ve been playing together in the studio, working for other people. Tal is a really, really talented bass player, and like anybody who’s known for a kind of virtuosity, there's so much more possibly. She and I are good friends.

“She wants to learn new ways of playing. She’s making an album full of her own songs. I don’t think anybody’s quite thinking of her as a singer-songwriter, but it hasn’t stopped her. She sang The Times They Are A-Changing with Herbie Hancock at this live thing, and she was just brilliant. She made this fundamental change in the harmonics of the song that was just amazing.”

I’m sure that you have a have a big guitar collection, but for this album, were there any real go-to models that you used?

“I mean, everybody played this little Martin OO-17 of mine. I played it on several songs, and Carlos Varela played it, and Greg played it, so that got a lot of use. The only other acoustic guitar would be my own Gibson model. It’s on If I Could Be Anywhere, and it was tuned down a whole step for that. The Gibson takes tuning down really well.

“Then I played a Telecaster on one song and a Strat on another, but it almost doesn't matter what I play. I mean, I’m kind of just a neophyte when it comes to electric guitar tones. What's interesting is that the really masterful players like Greg or Val really know exactly what they want to get and what guitar they want to make that thing happen. It’s sort of built into the filter – they know exactly what to reach for. It’s a big mystery to me.”

You’ve never been one to shy away from politics in your music. Sometimes the messages are overt, sometimes not. A lot of entertainers don’t want to rock that boat in any way. Do you feel as though it’s your responsibility as an artist to put forward a point of view?

“I think that, as a citizen, I feel responsibility to get to the bottom of some issues. I know a lot of people that care very much about corporate greed, about what's been done to the environment on behalf of a few people building their personal forts. I think it’s more that it’s just hard to talk about in a song because there isn’t a lot of room for exposition, and you can’t really marshal a lot of facts if you can’t back things up.

“One of the things that songwriters do, I think, just by their nature, they kind of cross-examine themselves. ‘Why do I feel that way? What am I, really? How do I really feel?’ It’s something you ask yourself continually. But how do you finish the song? Sometimes the question I have to ask myself in the middle of a song if I’m stuck particularly would be like, ‘Yeah, but what do you want?’"

Working with The Section

“You asked about the song Which Side? I think it was easy to finish that song once I got the track going because, in the first place, I wrote it and tried recording it before it had the bridge and one of the choruses. I don't know what to call them. A lot of my songs have multiple bridges – or I don’t know whether to call the verse the chorus or the chorus the verse. A good friend of mine, Jon Landau, complimented me on the song and said, ‘It sounds like it could use a bridge.’

“I didn’t really do anything about it. I wound up playing it, and I sort of demonstrated to myself that it really needed one, because I recorded a live version and I kind of tried to develop the way we were playing it without that bridge. Once I really elaborated on the question of ‘which side’ and how those sides are lining up… I mean, I don't know anybody who will claim to be on the side of corporate greed, do you?”

No, but I imagine there are a few of them out there.

“Yeah, but it doesn’t look like greed to them, or it’s like that famous Gekko character in the Oliver Stone movie Wall Street: ‘Greed is good.’ Yeah, there are people who believe that, but I mean, I think in the face what's happened to our financial system and what's happened in the environment… It’s harder for them to actually come up with that jive-ass bullshit.” [Laughs]

In the last year, I've been very fortunate to have spoken to Waddy Wachtel, Danny Kortchmar, Lee Sklar and Russ Kunkel. You worked with them all, and you toured with The Section [Kortchmar, Sklar, Kunkel and keyboardist Craig Doerge] for the Running On Empty Tour. In your view, what was the great thing musically about those guys back then?

“I think it was the versatility of Russ Kunkel. They’ve all played with a lot of people now, you know? Russell, for me, was my entrance into that group of players. I actually knew Danny – I probably met Danny around the same time, or maybe even met him before, but we never really played together. Russell was the kind of drummer who a songwriter like me could rely on.

“He had already played with James Taylor. He had played with Joni Mitchell so well and so beautifully. He was something of a mentor to me. He really invited me; he said, ‘Just so you know, I want to work on your record with you, so call me when it’s time.’ He was very welcoming.

“The thing about those players is, they weren’t the session assassins of the day. They were the younger version of The Wrecking Crew. They were a bunch of young, hungry guys that actually knew that they didn’t have to necessarily cut three songs in three hours, or get so much work that nobody else had any. They were able to develop a song and get inside the song in a way that not everybody had before.”

On SRV

“I was telling a friend of mine who’s a giant Stevie Ray Vaughan fan that I was going to be talking to you. He had no idea of your connection to Stevie.

“It’s not a huge connection. Like everybody who heard Stevie play, it was like, ‘Oh, my God! What is this? How is this possible?’ Imagine if you and I were sitting across the table from each other and somebody came rushing in saying, ‘You’ve got to come downstairs right now. There's something happening. You just have to hear this. Can you come now?’

“We just sort of went down to this club where he was playing, and as you can imagine, it was like a complete revelation. On that occasion, there was a bit of the sit-in, all that. I can't really say that it was much of anything but staying up late, getting high, and me yowling some blues lyrics I know. It wasn’t a jam. I’m not on the level that those guys were on.

“I just said to Stevie. ‘Well, if you’re ever in LA, come by. I’ve got a place that you can record some stuff if you want.’ I had just made my first studio. Well, Stevie happened to come to town, and he just called me from, like, Bakersfield or something, and he said, ‘We’re here. We're going to be there in about an hour.’ It was right at the end of a week, and it was the beginning of a Thanksgiving holiday.

“We all had places we were going to. When I look at it now, I wish I’d simply stayed, but I didn’t. I had a Thanksgiving thing planned. Greg Ladanyi, too – he had somewhere to be. But James Geddes, our second engineer, said, ‘I can do it.’ He just sort of stayed there with Stevie. They basically recorded the bulk of the Texas Flood.”

Oh, OK. I was always curious whether you ever gave thought to producing him and the band.

[Laughs] “God, no. I've got to say, it didn’t … OK, well, here's an admission. I really had no idea. I've been listening to blues my whole life, and I love blues, but it didn’t seem to me like it was as powerful a vehicle as it apparently was. I probably would’ve been thinking about how he could be used the way David Bowie did on Let’s Dance. ‘How do you we make some pop songs and use your guitar in them?’

“Which is far from the mark, far from what he did. He just stayed true to what the music was to him, and it was so compelling and so persuasive on every level – physically and emotionally and intellectually, too. I mean, he just killed it. I think we owe him so much. There was a lot of pop music that was based on blues, like Cream or any number of things. He just took it up a notch and took it down into the roots several notches, too. “

On producing other artists

“I’m just as astounded as anybody that it was that popular on its release, that it moved that many people. You only see that shit happen when it’s Jimi Hendrix. I loved Hendrix when I first heard him, and I was a little bit surprised that it was as popular as it was. I just thought, ‘Oh, really? Are people going to be into this?’ Does that sound foolish?”

No, I don’t think so.

“I felt that way about Warren Zevon, too. I just thought, ‘Well, no one’s going to get this but me.” I mean, I’m qualified to produce people like Warren because he'd already been around record companies for a while, and there weren’t a lot of people clamoring to make records for him, so we got that record made that way.

“I think my way of making records worked really for Warren, but once you’ve done it that way once or twice, you don’t need it anymore. He knows how to do that. He knows how to do what I brought to it. Not that I would’ve … I mean, I would’ve loved to work with him again, but at the time that Warren and I stopped making records together, it was because I had made four records back-to-back – two of mine, two of his. I had to go on the road. I didn’t have the time to make his next album anyway.

“As a producer, I know I’m a kind of slightly underqualified. Also, I’m under-ambitious when it comes to the marketplace. I just want the songs to be true, and I want the artists to be themselves. Even Lindley, when I produced his first record, I just wanted him to get to make the sound he wanted without having to deal with any kind of second-guessing from the record company. I’m more of advocate or something or a mid-wife, something along those lines.”

Joe is a freelance journalist who has, over the past few decades, interviewed hundreds of guitarists for Guitar World, Guitar Player, MusicRadar and Classic Rock. He is also a former editor of Guitar World, contributing writer for Guitar Aficionado and VP of A&R for Island Records. He’s an enthusiastic guitarist, but he’s nowhere near the likes of the people he interviews. Surprisingly, his skills are more suited to the drums. If you need a drummer for your Beatles tribute band, look him up.