Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

All of Rock Hall Of Famer Donovan's hits and more are on a new collection, The Essential Donovan. © WALTER BIERI/epa/Corbis

"It was a wonderful evening," Donovan says of last Saturday's Rock And Roll Hall Of Fame induction ceremony, during which he was honored along with Guns N' Roses, the Beastie Boys, Laura Nyro, the Red Hot Chili Peppers and others. "There's awards shows and concerts, but no night is truly like that one. I'm deeply honored to have been part of it."

Much of the talk surrounding the Rock Hall's 2012 class has focused on Guns N' Roses - more specifically, on Axl Rose, who declined to be inducted. Sitting down in the screening room of New York City's swanky Core Club, Donovan offers his own assessment of the situation: "It did seem as though the audience was upset by him not being there. Personally, I think he should have shown up."

The folk-pop troubadour, looking nowhere his 65 years of age, is in great spirits - his overall beatific countenance makes one wonder if he's truly has a bad day, ever - and during the course of our conversation, he talks easily of Dylan, The Beatles and The Rolling Stones. But the difference, of course, is that these are no mere historical figures to Donovan. These are friends, comrades - he was there when it all happened.

More than that, he was their equal, one of the most original and transfixing voices of the 1960s. Aided by producer Mickie Most, the music that Donovan Leitch created mixed folk, blues, pop, rock and beat poetry on an avalanche of hits like Sunshine Superman (featuring a pre-Led Zeppelin Jimmy Page), Hurdy Gurdy Man, Season Of The Witch and Atlantis - all of which are featured on the just-issued two-CD set The Essential Donovan (Epic/Legacy).

Donovan reflected on these tracks during our interview, a conversation which also covered topics such as pop stardom, the singer's supposed rivalry with Bob Dylan, how he came to teach The Beatles fingerstyle guitar and the role of the poet in modern culture.

You refer to yourself as a poet. But as a poet, how groovy was it to be a pop star in the '60s?

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

"Well, it was the poet in me that wanted to put the poetry together with popular culture. That was my mission in what we used to call 'the underground.' Before that, it was called 'bohemia.' In bohemian circles, we were very aware that poetry was missing from popular culture. In the '40s and '50s, that was the mission of beat poets - that was Rexroth, Kerouac and Ginsberg, Burroughs and McClure.

"They thought if poetry was returned to popular culture, with that would come meaningful lyrics, and with that, the poet's place in society would be returned. And that was dangerous…"

Why is that?

"Because the poet is the voice of the people. And when the poet presents certain ideas, two phrases in one poem can alter a generation's view. So poets have always been feared, and controlled, and jailed… and sometimes killed.

"My father read me all the great poets, and when I was a teenager, I loved the songs of social change - Pete Seeger and Woody Guthrie. But when I was 16, I realized that it wasn't enough for me to sing these songs of social change, peace and brotherhood and meditation for people in the folk clubs, poetry circles and art schools. This would have to go to the millions of young people let loose upon the world with the Baby Boom. I would have to take it to TV and radio and the mass audience.

"And it was easy! [chuckles] It was - because I loved Buddy Holly, and I loved The Everly Brothers, and I loved jazz and folk and blues. Now, what was it like to be a pop star? As I said, it was easy - because it was easy for me to be photographed. Part of being a pop star is image. I'm told by many of my female fans that I was the poster on their bedroom walls. But if I only had that - the image and the beauty and the curly locks - I would have been a 'normal' pop star, one who comes and goes after one hit record.

"No, I was more than that, although I was certainly a pop star. I was comfortable with it all. Coming from art school, I had a great sense of style - as did The Beatles and the Stones - and I enjoyed projecting that. Image, attitude, great music and great lyrics - that was the '60s."

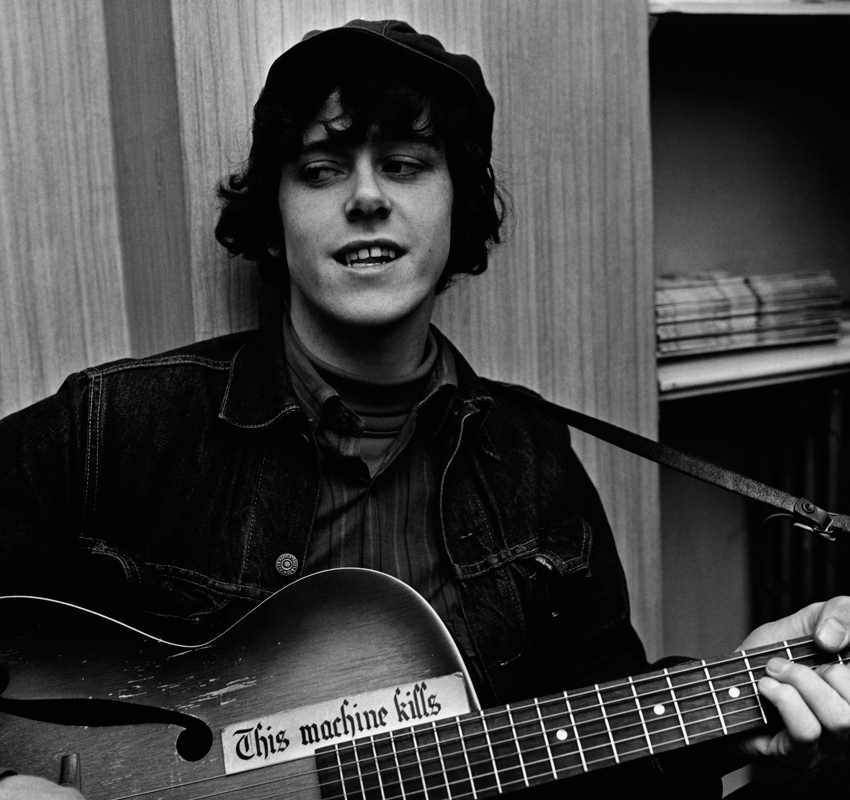

Donovan in 1965. The sticker on his guitar was a variation of Woody Guthrie's, which read, "This Machine Kills Fascists." © Hulton-Deutsch Collection/CORBIS

How did you learn fingerpicking? Who did you listen to in the early '60s?

"Well, at first I couldn't fingerpick at all; I used to flatpick. But I would sit in front of Jack Elliot, who was a student of Woody Guthrie before Dylan - this was when Jack would come to England - and I would watch him play. A few guitarists taught me the fingerpicking style.

"But I needed to know the actual clawhammer, which was from the banjo… There were only a few people doing the clawhammer in the folk clubs, and I would sit and watch them. When they saw what I was doing, they would turn their guitars away and give me the finger, as if to say, 'You're not learning it from me; you have to learn this for yourself.' You couldn't learn it that way.

"Into town one day came a guy named Dirty Hugh - he was called Dirty Hugh because he never bathed. But he was a beautiful man and he had a guitar, a Martin dreadnaught. He could fingerpick. I asked him, 'Will you teach me?' And he did."

Let's talk about Bob Dylan. In the documentary Don't Look Back, it seemed as if there was a rivalry between the two of you. But you were cool with each other, right?

"It did look like there was a conflict, didn't it? But not really. [laughs] I didn't hear Dylan first, I heard Woody. My cap and my harmonica was a Woody Guthrie thing. But one day, my pal Gypsy Dave called me and said, 'There's this other guy, Bob Dylan. I've just taken a record from my girlfriend…' We sat down and listened to The Freewheelin' Bob Dylan - it was just like Woody Guthrie. It was amazing! That was my introduction to Dylan.

"I met Buffy Sainte-Marie and Joan Baez at a folk festival - I was a young man, and these were young girls, and they played guitar, and I fancied them. [laughs] When Joan Baez heard me play guitar - I had already had a couple of records out - she smiled. She couldn't believe it. She said, 'You have to meet Bobby.'

"That May, the magical summer of '65, was when we met at the hotel. When the film came out, it looked as if there was a conflict. Dylan or Donovan? Stones or Beatles? It was played up: oh, Donovan is a copy of Dylan. But we were both taking from Woody. I absorbed a couple of Dylan's styles and tried them out, like any artist would. But I realized that he was drawing from a very heavy Celtic, British-Irish tradition."

Mickie Most's production of your work was quite revolutionary - and very successful. Jimmy Page played on Sunshine Superman. What was that like working with Jimmy?

"It was wonderful. It's important to remember that I wasn't a band; I was a singer-songwriter and solo artist. Bands write riffs between the members. When I met Mickie Most, I had met my great partner in sound. See, I knew the sounds, the parts I needed to hear. Mickie listened to my songs, and I told him what I heard. He said, 'Stop. You need an arranger.' So he introduced me to John Cameron.

"John would work them out with me, the arrangements. He'd write down the parts, everything I heard and talked about. So Jimmy Page came to the Sunshine Superman session and was given the music. Now, he's not in The Yardbirds, he's not in a band, this isn't jamming - he's a session guy, and he's learning parts. This was a jazz-fusion of rock 'n' roll. Jimmy learned the parts, but he was free to do what he wanted. And I loved it. Jimmy is a master. I was so lucky to have him on my record."

Season Of The Witch is a heavy blues song. [Donovan nods and smiles] What did you think of what Al Kooper and Stephen Stills did with it?

"That was the second cover I had heard of it; the first was by Brian Auger and Julie Driscoll. It now would become a Hammond organ player's dream come true. When I heard the Al Kooper and Stephen Stills Super Session version, I loved it. It was fantastic! At the Rock And Roll Hall Of Fame the other night, I ran into Billy from ZZ Top, and he leaned in to me and said, 'By the way, man, we used to do Season Of The Witch in our show.' It's really something, all of these covers."

Hurdy Gurdy Man was directed at the Maharishi. What did you think of how John wrote about him in Sexy Sadie?

"See, many people talk about John and whether he was disillusioned with the Maharishi. It's clear to those of us who were there, and John realized it, that there was a Rasputin in The Beatles' camp, and that Rasputin was Magic Alex. Alex didn't like the relationship John had with the Marharishi.

"The fame The Beatles had was 10 times what everybody else had, even mine. It was unbelievable. At this time in India, John was leaving Cynthia, he had lost his manager, the audiences were mobbing The Beatles… the band's well-being was threatened. John had learned meditation, but all it took was one suggestion from Magic Alex that the Maharishi was bad, and that turned John's head around. The truth was, Maharishi wasn't bad, and he wasn't having affairs with the female students. John wrote those things, and he kind of regretted them later."

During your time with The Beatles in India, you taught them fingerpicking. How did that come about?

"I didn't know at the time that I would be showing the three main songwriters in The Beatles - John, Paul and George - fingerstyle. They had spent so much time in Hamburg absorbing so much music. They were so brilliant, and they knew music so well, but one thing they didn't learn was the combinations of the folk-blues-classical-flamenco-New Orleans-jazz progressions.

"In India, I sat around playing the guitar. I never stopped. I felt naked if I didn't have the guitar. Ringo used to say, 'Donovan, you never stop playing the guitar, do you?' [laughs] One day, John said, 'How do you do that? That fingerstyle, that picking, will you teach me?' So I showed him. And Paul would stand around, he'd steal a look and then he'd walk away into the woods. He was listening. A smart boy, our Paul. And from that, he wrote Blackbird.

"John came up with Julia and Dear Prudence. And George liked the chord progressions, and under that great shadow of John and Paul, he came up with While My Guitar Gently Weeps. It was a great pleasure to pass these styles on. That's why The White Album is so fantastic... and so acoustic."

Backed by youngsters at the Isle Of Wight Festival, 1 September 1970. © Bettmann/CORBIS

Atlantis is famous, of course, in that it featured spoken word. There weren't many songs like that at the time.

"Very few. There was the one Richard Harris did. What was that…?"

MacArthur Park.

"Yes, there was that. And there was The Green Berets. Spoken word isn't usually done in pop, but that's what I felt. I learned from reading poetry as a kid how to do that."

What did you think of the use of Atlantis in the movie Goodfellas?

"People ask me about that. I embrace the use of my songs in film, TV and commercials - you reach so many people that way. When I was asked about the use of Atlantis in a Martin Scorsese movie, I said, 'Whatever Martin wants to do, he can do.' A song of peace in a violent scene… it's the juxtaposition that works. I don't condone violence, and the scene shocked many of my fans. But it shows the futility of violence."

You said that it was easy to be a pop star in the '60s, but was it ever difficult in that you felt your message wasn't getting across, the people weren't really listening?

"The fact that the songs came to me… and Dylan has said this… I think that writers have a skill to create circumstances to create. To imagine that the songs can be popular is difficult. To imagine that your fame can be super like The Beatles or The Stones or Dylan or me is difficult. But you do wish to communicate. If you do communicate, and if you do achieve super fame, you lose your private life. That is hard.

"For The Beatles, it was dangerous, even fatal. They lost their private lives altogether. For me, the difficulties weren't in wanting to communicate, it was in doing so at a time when we became heroes and heroines… and we became victims of our fame."

Joe is a freelance journalist who has, over the past few decades, interviewed hundreds of guitarists for Guitar World, Guitar Player, MusicRadar and Classic Rock. He is also a former editor of Guitar World, contributing writer for Guitar Aficionado and VP of A&R for Island Records. He’s an enthusiastic guitarist, but he’s nowhere near the likes of the people he interviews. Surprisingly, his skills are more suited to the drums. If you need a drummer for your Beatles tribute band, look him up.