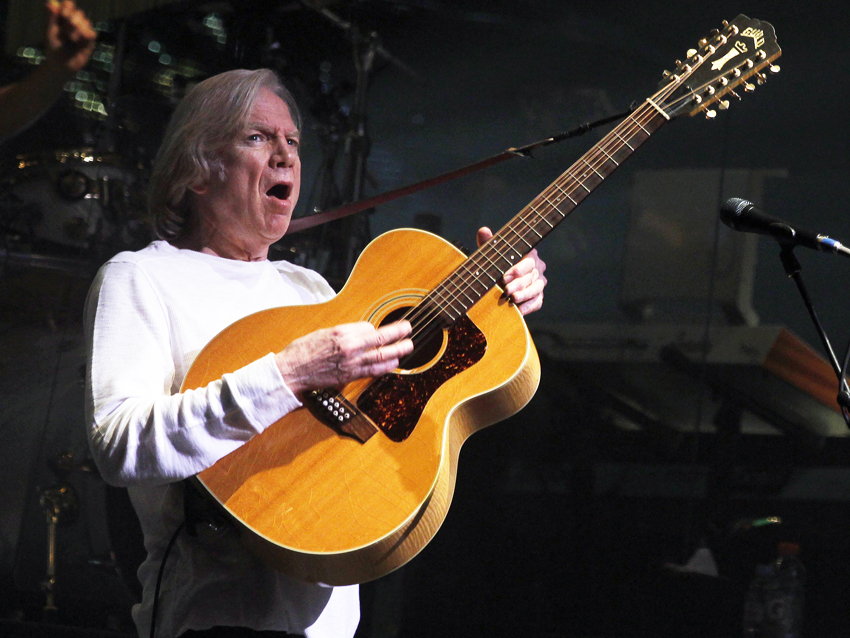

Justin Wayward on The Moody Blues' Nights In White Satin

“It’s a song that never seems to go away," says The Moody Blues' Justin Hayward of the band's pop/proto-prog orchestral masterpiece and perennial hit Nights In White Satin. "It was a slow build, and of course, it was released a few times, but once it took hold, it did so in a really big way. It seemed to get into people’s minds and just stay there. The whole thing's very strange and wonderful."

The lush, transporting and immersive track, which appeared as a full-blown epic (clocking in at over seven and a half minutes, complete with a spoken-word poetry section called Late Lament) on the band's 1967 album Days Of Future Passed, was released in edited form as a single in November of that year. The song reached the top of the charts in France, but in the UK it only got as high as number 17.

“It was fantastic to hit the top in France, but of course, we were hoping to repeat that success elsewhere," Hayward says. "Once it dropped off the UK chart, that seemed to be it for the song." He laughs, then adds, "For a while, at least. As we all know, it came back bigger than ever, and it's had all of these different lives over the years."

In the following interview, Hayward recounts the writing and recording of The Moody Blues' signature song, as well as its unexpected re-entry into the charts in 1972, an occurrence that the singer says "changed my life and the band's lives forever."

Walk me through the writing of the song. As I understand it, you started it when you were 19.

“Right. It was in early 1967, and I’d just come home from a gig. I was living in a one-room flat. I sat on the side of the bed and wrote the basic two verses and two choruses with a 12-string acoustic. I took it to the rehearsal room the next day because the guys were expecting me to have something to work up for a stage show. I played it for them and they were like, ‘Huh… it’s OK.’ I don’t think they were that thrilled – they didn’t hear it straightaway.

“But then [keyboardist] Mike [Pinder] said, ‘Play it again,’ so I did. I sang ‘Nights in white satin... ’ and he did that little 'da da da-da-da-da-daaa’ on the Mellotron. Then everybody seemed to get interested; it made sense to them. Once he delivered that phrase, which is really quite important, the song started working for them.”

On recording

The song, along with the album Days Of Future Passed, came out in 1967, during the height of The Beatles' Sgt. Pepper period. Is it safe to say you guys were influenced by them a bit?

“Oh, sure, more than a bit. I'd admit that, and I think other musicians who were around at the time would, too. To be part of the musical scene in London during that whole period was amazing, and The Beatles were our leaders, undoubtedly. They showed us the way. Sgt. Pepper and Strawberry Fields and other songs they did at the time – they gave us the freedom to try anything.

“Obviously, we didn’t have the power or the money that The Beatles had. They could indulge every whim in the studio and basically do whatever they wanted. We had to catch a lucky break with Days Of Future Passed. That lucky break from Decca, who wanted a demonstration record for their new stereo systems, and that’s how we got to make the album.

“To be honest, because we made the album as a stereo demonstration record, I thought that only a handful of people would even get to listen to it because only a handful of them had stereos at the time. What I didn’t realize was that FM radio was starting to take off in America, and the DJs and programmers were starved for good stereo records. Even The Beatles had mono records at the time, which sounded great, but the people were starting to want stereo."

Like Sgt. Pepper, the album was recorded on four-track?

“We did everything on four-track. It wasn't as elaborate as it might seem at all. We recorded it at Decca Number One in Broadhurst Gardens, West Hampstead. We put our songs down, and then [producer] Tony Clarke, [engineer] Derrick Varnals and [composer] Peter Knight] bounced that with Peter recording a count through the entire 48 minutes. Then the orchestra came in for a three-hour session, and they rehearsed to a tape with our tracks and that count. So our tracks were finished in stereo, and then the orchestra, after a tea break, played their parts and recorded on that. That was it.

“By the way, it's called The London Festival Orchestra, but that's just a name that we made up. It sounded right, but they didn’t actually exist. It was just a group of gypsies – that's what we called them – these string players that would do a lot of sessions. Peter Knight put them together. He was signed to Decca, and he did the orchestral arrangements between our songs for the album."

The poetry section, the Late Lament, was that always a part of the song?

“That came about because we needed some kind of summing up of the story. We had a feeling within the band that everybody should contribute, not just me and Mike. [Drummer] Graeme [Edge] didn’t think that he had anything to contribute musically, but he did want to write something that pulled the Days Of Future Passed story together, which is the story of the day in the life of one guy, really.

“That’s where that came about. So Mike did the poetry reading. He had such a beautiful, charming voice – mesmerizing. He could persuade me to do anything with that voice of his. So his voice doing the poetry section really made the whole piece feel complete. He did the recording in the dark while lying on his back, with the rest of us sitting around quite stoned.” [Laughs]

The re-release in '72

You would perform Nights In White Satin on stage before it was re-released in ’72. Was there an overnight difference in the crowd response once they heard it on the radio?

“Oh, yeah. But funnily enough, that started building from about 1970, although yes, once it became a radio hit, the difference in the response was enormous. You have to remember, the 1960s were about singles. The indie promotion guy at Decca, back in ’67, when Decca wanted to release it, said, ‘Nah, I can’t plug that. It’s four and a half minutes, it’s slow and boring – it’ll never do anything.’ He washed his hands of it. That was rather upsetting.

“He was right, to a certain extent, but then the culture changed. The Boxer changed quite a few things. That song was long and lilting. Sometimes you just have to give yourself up to a song – let it wash over you.”

Although leading up to the re-release, there was no real thought to putting the song out again – it just seemed to happen on its own.

“There was no grand plan behind the whole thing; in fact, the record company tried to suppress it. We had another album at the time to promote, Seventh Sojourn. They didn’t want us to be competing with ourselves, really. But once DJs got their hands on Nights again, they decided they were going to go with it. Before you knew it, there was no turning back.

"And what I think happened was, everybody seemed to know the song in a way – they knew it a little bit – so when it was put out again, people responded very quickly. I guess that were primed for it, having heard it maybe years earlier. They didn’t have to get used to it again – it was already in their consciousness somehow. So it was great – in '72 the song was finally a real hit.”

Do you prefer the album version to the single?

“Actually, I liked the single – I never had a problem with it. Actually, many months before we recorded it for the album, we had recorded it for the BBC. It was for a show called Easy Beat. It was broadcast the day after we taped it. I remember we were in our van going up the motorway, and we listened to the show on the radio. As it played, we were saying things like, ‘Fucking hell, there’s something about that performance…’ By the end of it, we were all sold – it was brilliant.

“We phoned up the BBC straightaway and said, ‘Can we have a copy of that song called Nights Of White Satin?’ And they said, ‘No, we wiped it. We use the tapes at the BBC to record again.’ That sent a few of us, including myself, into a bit of a spin. I had to convince myself that we could still do it again, that the BBC version, as magical as it was, could be topped.

“Three or four months later, when we got to record it for the album, I wasn’t completely convinced because I still thought there was a better version around. It’s just that I couldn’t compare it. It was a very odd thing."

Cover versions

Do you feel as though the success of the song changed people's perceptions of the band?

“I think it gave people a clearer idea of the sound of the band. Everybody had a specific part to play on the recording; it was the definitive sound of The Moody Blues. From the vocal performance to the high backing vocals to the Mellotron and the echoes – it’s all there. Be it the single version or the full album version, you get the entire picture of the band in that one song."

The track in '72 hit number one on Cashbox but only got to number two on Billboard. Was that upsetting – to be so close to number one?

[Laughs] “Well, sure. I’ve got it on Cashbox that it went to number one, but of course, Cashbox means nothing now. Billboard is seen as being the definitive chart. It’s like what happened with the song Question, which reached number one for us in 1970. It reached number one on all of these other charts except for the BBC chart – they had a BBC record at number one. So these other charts have disappeared, sadly. That's just the way it goes."

In addition to The Moody Blues recording, there have been many cover versions over the years.

“Which is always a compliment. I did notice that a girl did it on America’s Got Talent recently, and then, of course, it takes off again – people start gravitating toward it. Three years ago, I was sent a version by Bettye LaBette, a French soul singer, and when I heard it I was moved to tears. My wife came into the room and asked me what was wrong, and I said, ‘Listen to this.’ It’s a very curious thing to write a song at 19 or 20 years old and then to be 65 and hear somebody else discovering it and making it their own. I hear a lot of different recordings of it, and it’s amazing – I hear it as a new song every time.”

Shifting gears here – you have a new solo release, the Spirits... Live Blu-ray and DVD.

“Yeah, that was a wonderful opportunity. On the first solo tour, I had a lot of success with the Spirits Of The Western Sky album that I had out last year, and I decided to support it with a tour. Promoters wanted to see if there was any mileage to Justin with an acoustic guitar. Halfway through the tour, I thought, ‘I might never do this again, so I’d better record it.’ I’m very glad that I put it together. It’s a great little snapshot in time.

“The funny thing is, speaking of things taking on lives of their own, that’s what happened here: I’ve done another two solo tours, and I’m just about to start another one. I’ve got a great young kid with me, Mike Dawes. He’s a wonderful, marvelous guitar player, and he sustains me very well. And Julie Ragins, who works with the Moodys, is one of the greatest musicians I’ve ever known. She’s got the voice of an angel. It’s something that I enjoy. It’s a complement to the Moodys, but it’s also the perfect counterpoint to the big production that is the band.”

Justin Hayward's Spirits... Live: Live At The Buckhead Theatre, Atlanta can be purchased at Amazon.

Joe is a freelance journalist who has, over the past few decades, interviewed hundreds of guitarists for Guitar World, Guitar Player, MusicRadar and Classic Rock. He is also a former editor of Guitar World, contributing writer for Guitar Aficionado and VP of A&R for Island Records. He’s an enthusiastic guitarist, but he’s nowhere near the likes of the people he interviews. Surprisingly, his skills are more suited to the drums. If you need a drummer for your Beatles tribute band, look him up.