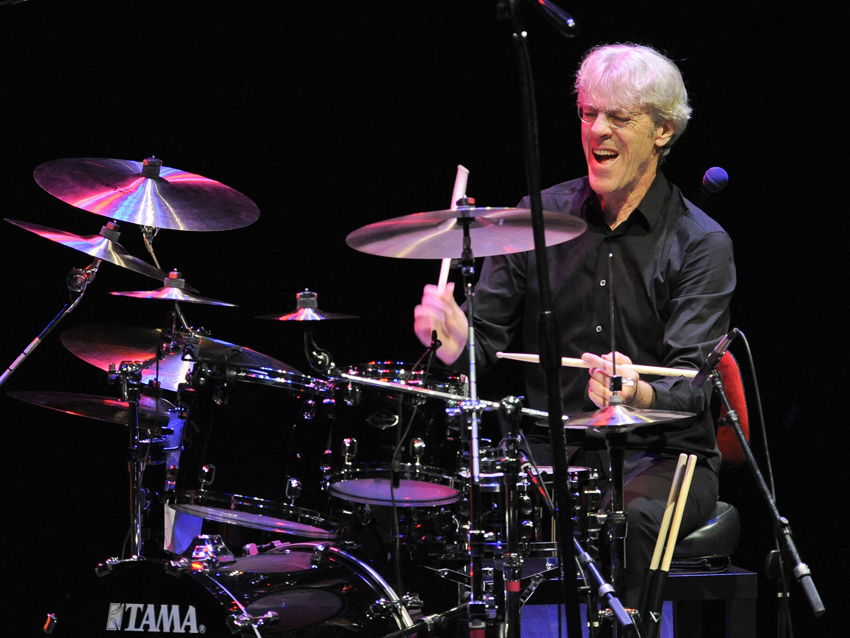

Stewart Copeland's top 5 tips for drummers

How do you follow a band like The Police? If you're Stewart Copeland, you write a new soundtrack for Ben-Hur and perform it with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra. Or you write an opera called The Tell-Tale Heart, based on Edgar Allan Poe. Or you record and tour with bass legend Stanley Clarke. Or maybe you become a classical composer and see your works performed by the Dallas Symphony Orchestra and the Royal Liverpool Harmonic, among others.

“My day job is being an artsy-fartsy, fancy-schmatzy composer," Copeland says. "Right now on my desk I’ve got commissions from the Royal Conservatory in Toronto, the Pittsburgh Symphony, Chicago’s Theatre Opera, the Long Beach Opera and the Iceland Symphony. All of these charts are on my desk, pending right now.”

At night, Copeland swivels his chair away from his computers and changes gears, rocking out with friends who come by to jam at his Sacred Grove Studio. "My studio is like a giant train set, and I’m a glorified roadie," Copeland says. "I love to crawl around under the gear and hook stuff up, fiddling with mic placements and stuff like that. The musicians that come over to the Sacred Grove are the trains that I get to play with.

"We have a blast. I've got videos of Danny Carey, Neil Peart and me blasting away; there's Ben Harper, Stanley Clarke and me; Snoop Dogg and Armand Sabel; and I had Andy [Summers] over here one night with Jeff Lynne. We had a jolly dinner and then I dragged them over to the Grove. As always, shit happens."

With all of this varied musical activity, you might think that Copeland would never find himself in a creative rut. He allows that he does happen – occasionally. “To get out of that rut, you need to turn to Shirley & Spinoza Radio," he advises. "Expose yourself to new shit – that or pick another instrument. Those plateaus are more of a problem for a beginning player, maybe in the first years of their growth; maybe in the first 10 years or the first few years of their professional career. You feel as if you’re growing and it’s exciting, and then suddenly you get to a certain place and you just can’t get past it. It’s absolutely common, and pushing through is what it’s all about."

He pauses, then adds, “One of the great miracles of art is that new stuff happens. Every day I come here, and I still get new tunes, new ideas. I don’t know where it comes from. I don’t know how it is that all the songs haven’t been written – by everyone else, let alone me.”

On the following pages, Copeland offers more sage advice, his top five tips for drummers.

Relax for power

“If you listen to the really powerful drummers, you’ll notice that they’re actually very relaxed when they play. Let’s take John Bonham, who’s probably the mountain of power – he’s got a very relaxed, easy style. His contact with his sticks, and the way they hit the drums, is very relaxed. This gives you a lot more power, far more than other drummers who clutch their sticks tightly, tense their muscles and attack the drums with ferocity. You actually achieve more impact with relaxation.

“It’s sort of like the young bull and the old bull looking down from the hilltop at all the hot cows. The young bull says, ‘Hey, let’s run down and fuck one of those cows!’ And the old bull says, ‘Let’s walk down and fuck all of those cows.’

“This concept took me a while to realize, probably about 30 years – no, make it 50 years. The epiphany came from playing with an orchestra. You might think that having 60 guys blasting away is quite loud, but it actually isn’t. It’s powerful, but the true volume level is very low compared to one Marshall amp. My career of playing with big, bad amplifiers, with a dynamic range of five to 11, didn’t prepared me of playing with orchestras where the dynamic range was from four to zero. And even then, the oboe that’s playing the beautiful little melody that I wrote, that’s acoustic. There’s 60 guys on stage, but they’re not always playing; sometimes it’s just that oboe.

“I had to learn how to play quietly. In pursuit of this new dynamic range, I discovered that the drums sounded so much better, and all the technique was easier and more relevant, when I played in a relaxed manner. There’s all kinds of blessings that come with it.”

In the drum room, practice slowly for speed

“You won’t achieve that fast single-stroke roll by pressing yourself and saying, ‘Faster, faster, faster!’ You’ll get it by evening out your wrists and playing slowly and correctly. When you do it slowly and your muscles learn to do things correctly, then when speed is called for in moments of high drama on stage, you can pull it out and play it better and faster than you would in the practice room.

“In practice, you’re looking for perfection. To achieve that, you look for the right speed where you can get your rudiments perfectly and you never go above that. Because in practice if you go above that and you play imperfectly, then you’re teaching yourself ‘wrongness.’

“There’s the drum room and there’s on stage – very different rules apply. In the drum room, you’re thinking about yourself; you’re obsessing over every detail of your technique, how to improve it, how to streamline it, how to even it out and tidy it up. You achieve that by doing it well within the bounds of what you can execute.

“The miracle is that, when you’re on stage or in the band room playing for real, and all the adrenaline and excitement pulls it out of you, it’s there. You’ve got it – way more than when you were focused on it.”

In the band room, play outside of your instrument

“This means that you’re listening to the band and everything around you, not yourself. It’s the opposite of being in the drum room where you’re listening to yourself and working to improve what you’re doing.

“In the band room, you’re focused on the band and you’re not thinking about yourself at all. You’re not thinking about your rudiments or the ‘correctitude’ of what you’re doing. You’ve past the exam, you’ve got your diploma, so you’re not obsessing on that stuff. Now you’re listening to what the other people are doing. You are the bassline. You are the vocals even. That’s what your mind is on.

“And what happens is, you’re not inside your instrument; you’re outside your instrument. Your whole consciousness is about where you are in the song and what the rest of he band is doing.

“I learned this one early. To get the band rocking, which is the drummer’s job, you really have to feel the band around you and be that unifying force. To be that, you have to be in there with them and get outside of yourself. This is really all about getting away from the obsession with yourself. ‘I’m gonna play a drum fill now’ and stuff like that. If you’re thinking about the band, your hands will supply what the music needs.”

Be prepared to think on your feet

“Rock ‘n’ roll musicians generally find out on the day what’s to be expected of them. Whether you’re a session drummer or you’re showing up for rehearsal with the band, you’re basically expected to think on your feet. You hear the groove and you come up with something.

“If there’s any opportunity for you to be prepared, particularly if they’re paying you by the hour, take it. If you can get an inkling of what the material is going to be, if you can get a read on the vibe of the artist – anything you can find out can be beneficial.

“It’s not uncool to show up prepared for the gig. Do your homework. You can do the pose of ‘Hey, what are we doing today?’ – that’s fine. But make sure you’ve checked it out before you’ve left home. Google the artist and learn anything you possibly can. If you’re prepared, you can think on your feet, and you can come up with cool shit and be creative.”

Warm up

“It’s a simple fact that the second or third song in the set are better than the first song. They just feel better – everything’s better. If you can get yourself to that state in the first song by warming up, which is stretches and rudiments, then that’s a good thing.

“Warming up means you’re pumped – you’re not waking up and walking on stage. You’ve got your heart rate going. You’re relaxed but alert. Your wrists are loose and ready. If the guitarist is running through scales backstage, that’s great. Drummers can use a towel and run through stuff.

“Stretching is so important. I could talk for hours about the science of stretching every muscle in your forearm and under your wrist. There’s a knuckle for each one of those that you can pull on, and the results are pretty astounding. If you can do those exercises – bending your wrists this way and pressing down on each knuckle so that you can find each muscle on the top of your forearm, and then bend your hand back and pull each fingertip so that you can feel exactly which muscle is underneath your forearm – you’ll pick up your sticks and find that your technique is ‘Wow!’

“It’s not always possible to warm up properly. But if you’re on tour and you’ve got your dressing room and enough time, there’s no excuse not to.”

Joe is a freelance journalist who has, over the past few decades, interviewed hundreds of guitarists for Guitar World, Guitar Player, MusicRadar and Classic Rock. He is also a former editor of Guitar World, contributing writer for Guitar Aficionado and VP of A&R for Island Records. He’s an enthusiastic guitarist, but he’s nowhere near the likes of the people he interviews. Surprisingly, his skills are more suited to the drums. If you need a drummer for your Beatles tribute band, look him up.