Adrian Utley: “Playing guitar can be so many things. It’s been my salvation, my way of making a living”

The Portishead guitarist reveals his prized gear and reflects on his career

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

A decade on from Portishead’s last album, we drop in to visit Adrian Utley at his home studio in Bristol to talk about making music in the past, present and future…

Prior to teaming up with Portishead, Adrian Utley was revelling in playing at the top of his game as a session guitarist with Jeff Beck. Other guitarists might have been content to rest on those laurels. However, his restlessly enquiring mind was intent on pushing beyond the normal realms of the guitar and into sublime, unexplored and undefinable new musical areas.

Inspired by the liberated ethos of free jazz, along with the fearless conviction of DIY punk and hip hop, Adrian’s unique musical vision soon found its perfect setting in the influential Bristol trip-hop outfit Portishead, as they gracefully unveiled their game-changing Dummy album in 1994 (followed by a further two full-length LPs to date: Portishead in 1997, and Third in 2008).

In the best possible sense, he remains hard to pin a label on - either as a producer, composer or guitarist

Adrian’s interests also extend beyond guitars into synthesizers and production. This means that he’s typically involved in a range of collaborative projects, both on stage and in the studio.

In the best possible sense, he remains hard to pin a label on - either as a producer, composer or guitarist. Often leaning towards the retro-futuristic, previous interpretations and reworkings by Adrian include The Passion of Joan of Arc soundtrack (with Will Gregory) and Terry Riley’s In C (with Adrian Utley’s Guitar Orchestra).

Other strands of work have seen him opening new creative doors hand in hand with artists such as Marc Ribot, Marianne Faithfull, Patti Smith, Mark Linkous, PJ Harvey, John Parish and Anna Calvi, whilst remaining firmly in touch with his roots in the surrounding guitar community as both a mentor and educator.

Today, Adrian is typically hard at work in the recording studio nested on the top floor of his Bristol home. He takes a rare pause to reflect upon his 25-year long multi-platinum career in a band that managed to not only break new ground, but also help define an entirely new musical genre.

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

Few guitarists will ever be in a position to shrug off such claims as hyperbole and, although aware of the band’s obvious success, one gets the distinct impression that being typecast as a pioneer of ‘trip hop’ isn’t high on his agenda. After all, he’s far too busy immersing himself in one of several projects currently underway outside of the Portishead sphere.

1948 Gibson L-12

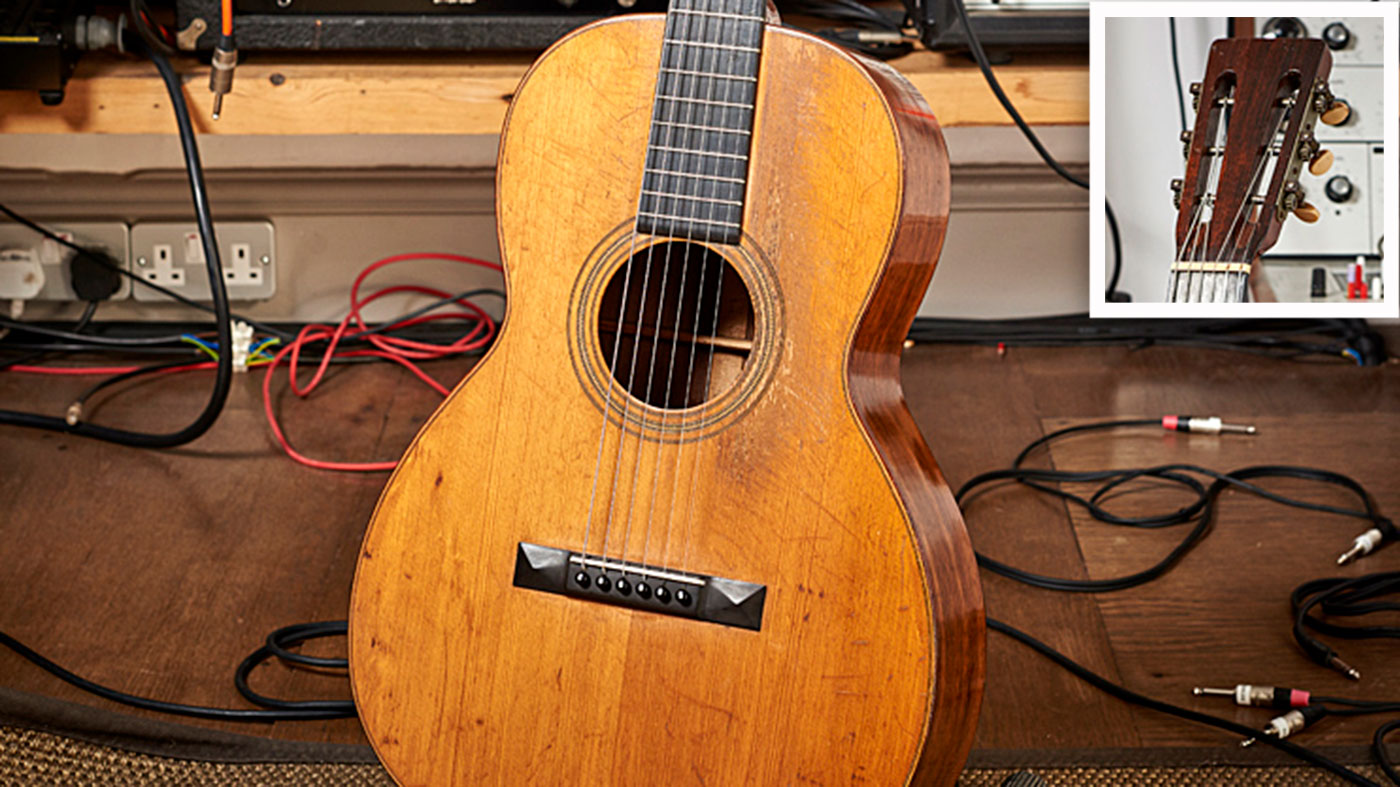

1929 Martin 00-21

Pedals

Trip(tych) hop

What are you working on today?

“Right now, I’m writing half an hour of music for a concert in June at the Elbphilharmonie concert hall in Hamburg with Will Gregory [of Goldfrapp] and Martyn Ware [of Human League]. It’s part of an electronic music festival and is a three-part triptych called Almost Human. There are going to be eight synths with a massive surround sound system in this huge concert hall. It’s such a lot of work that it seems mad to do it for just one gig, so we’re going to try and do some more with it. We’ll see what happens.”

It sounds like things have come a long way since working as a session guitarist. How did the transition to Portishead occur?

“Back in the early 90s when we were making the first Portishead record [Dummy] I was playing with Jeff Beck - a massive hero, y’know. Clive Deamer [Portishead drummer] and I did a Gene Vincent and Cliff Gallup tribute record with him called Crazy Legs [by Jeff Beck and the Big Town Playboys]. We made the record and then did a gig in Paris. It was amazing playing with Jeff - his dynamic and power. He was really kind to me and was very into what I was doing.

Portishead's Adrian Utley talks vintage gear and sonic adventuring

“I remember playing him some early Portishead demos. I’m not sure he totally got it because it was very early on and was unprecedented in terms of sound - I mean it was a pretty odd sound. I was really into hip hop and was starting to move away from guitar. I was fed up with a lot of the things I was doing. We were looking backwards, as well as forwards, in terms of hip hop and new ways of making music.

“I got to play with Jeff at a point in my career when I’d had enough of playing guitar and guitar playing. Jeff’s amazing playing and energy helped me, but I was more interested in beats and synthesizers and production than guitars. I was interested in finding out about sound and it’s been a massive learning curve ever since I changed from being a low-level session player - playing every blues club in Europe and every shithole in England - to re-thinking everything.”

How did you go about integrating guitar so seamlessly into electronic music?

“To integrate the guitar into electronic music, I became less choosy about my sound. At one time I would never have considered using even a transistor amp, but sometimes the natural sounding setup - like a blackface Fender amp, a nice ES-335 and no pedals - just wasn’t applicable to the situation I was in and I was trying to force this sound into a situation that people didn’t really want on their records.

“I began to realise that a lot of the people that had come before me - all the guitar players that I really loved - made their guitar sound fit with the track. It’s so important to do that, but it’s easy to overlook, especially when we’re so obsessed with gear. It might be a wicked guitar sound, but does it sound right in the track? That was a big realisation for me.”

Adrian’s vintage amps

1962 Fender Jazzmaster

Orange AD30

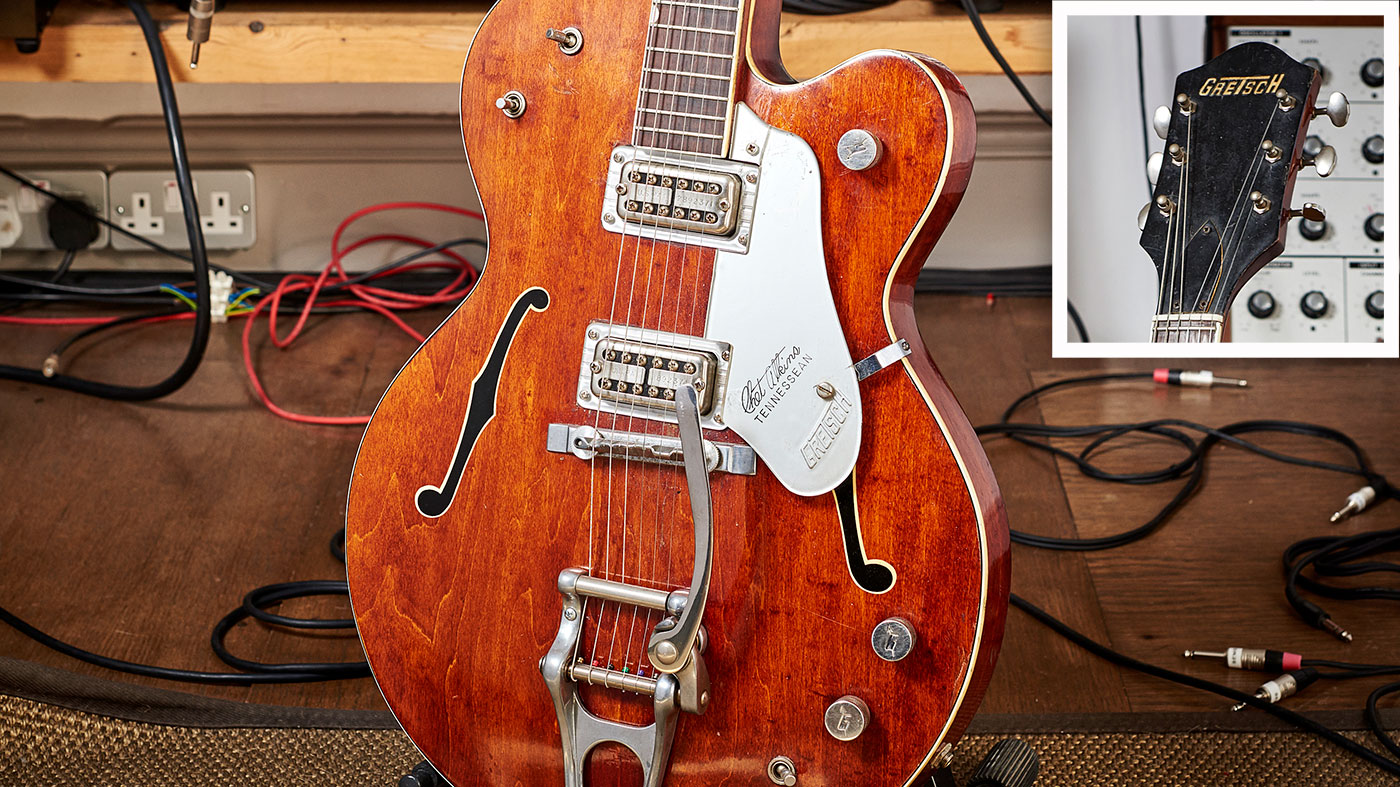

1963 Gretsch Chet Atkins Tennessean with vintage Filter’Trons

Tracking down tone

Did you have a specific sound in mind with regards to Portishead?

“I think Geoff [Barrow] did early on. I joined them after they’d been working for a year or so. We pretty much dumped all the material they’d been working on, but he had an idea in mind which I became involved in and so I started writing and creating sound as well. We had a collective picture of what it would look like, but it was really a gut [feeling] thing and we didn’t have much knowledge. It developed but we hadn’t yet. It’s like all bands: you have a feeling about what it is you’re trying to do, but it doesn’t always work.

It’s about production and seeing your instrument in the big picture

“I remember tracking up loads of Ebow for the song Roads, but I didn’t know how to use an Ebow then and it drove me absolutely mental! I had this picture in my mind, but I just couldn’t realise it. I couldn’t make it work. That can happen when you’re experimenting with all sorts of stuff and trying things that you think might work.”

What did you conclude generally from experimenting with guitar sounds?

“The thinner the guitar was, the more it fitted in, because the drums took up a lot of space. Same with Beth [Gibbons’] voice - it had to be thin. She’s got a massive voice if she wants it to be, but it wasn’t applicable. It’s about production and seeing your instrument in the big picture.

“In an orchestra, it’s pretty well delineated how the violins will sound together and what space the different instruments take up; this was built up over centuries of instruments being added, but with a band you can all crowd into the same frequency, because we don’t really know what we’re doing sometimes. Y’know, sometimes you can’t hear a guitar because a snare drum is in the same frequency - stuff like that. Let go of your desire to make the best guitar sound on its own and make it part of the track. In terms of playing on other people’s records, that’s entirely what you need to do. It’s not about solos. I did do a solo on Glory Box but there weren’t any other solos particularly.”

How did you write the guitar parts on Dummy?

“They were mostly written on the spot to loops. Something like Sour Times was pretty much written anyway because it’s a massive sample of Lalo Schifrin’s Danube Incident. In those days, we took the samples from live records, so the tempo would not be consistent. We sampled one bit and it would be at a different tempo in another bit. That meant when I played on it, the choruses and verses would be out of tune, so I had to retune [the guitar] to play both parts. You think your brain can’t detect it, but I think it does. Guitars aren’t perfectly in tune anyway. The fretting is wrong. But then The Stooges wouldn’t sound like The Stooges if the G string wasn’t sharp. We love that rank sounding open E chord, don’t we? We’ve gotten used to it, I guess.”

1969 Gibson Southern Jumbo

Roland Space Echo RE-201

1966 Fender Jazzmaster

Pedals

Tape to the stage

Is it challenging translating Portishead recordings for the stage?

“Yeah, it is. When we first started it was quite a difficult thing to do. We had the same aesthetic and various techniques that we still use today. Everything is live - nothing is ever playback. I don’t think any of us would want to do it if we were using playback. [Clive Deamer’s] drums on Dummy were recorded in State of Art studios onto ½-inch 16-track tape, sampled, mixed, put onto vinyl then fucked up a bit and resampled off the vinyl. We had to go and get test pressings done. Same as the guitar on tracks like Mysterons - that went onto vinyl and was resampled.”

Listen to Mike Bloomfield or Muddy Waters, none of those things sound like an amp in a room

That’s an incredibly dedicated experiment! What were you trying to achieve?

“Oh man, it went on! Geoff comes from a DJ/sampling background and would get rare records from Andy Smith, a DJ and collector. If anybody had been sampling, say a snare drum, on one of those records (as those guys did) it would wear the vinyl out.

“If you listen to bands like Public Enemy or A Tribe Called Quest, you can hear in the samples that the snare would sometimes go very dull - like on one snare. So, to replicate that, we’d record a drum break and Geoff would get it on vinyl, then he’d chuck it on the floor and kick it around, so it was a bit crackly, get it on his deck and just scratch on the snare drum bit to make it go dull. That’s the sort of attention to detail that made the record.”

What were you aiming for using the same lo-fi vinyl techniques with respect to guitar sounds?

“You know when you’re sitting in a room with a Fender amp and a Strat or a Tele and it’s just very live sounding, whereas it never sounds like that on records? If you listen to Mike Bloomfield or Muddy Waters, none of those things sound like an amp in a room to me. They sound like a record. Axis: Bold As Love is such a brilliant recording, but Hendrix doesn’t sound like he’s in a room, does he? It’s the same thing - trying to find a solution to the thing you’re trying to make.”

1959 Guild T-100D

WEM IC400 Vari Speed Copicat

Pedals

1960s Harmony H54 Rocket

1960 Watkins Westminster

Hendrix how-to

How did Jimi Hendrix’s approach to sound inform your own sense of aesthetic?

“I don’t think Jimi Hendrix thought about playing guitar as a guitar player, otherwise he wouldn’t have played like he did. He was thinking out of the box. He was into guitar and could play blues and soul like nobody’s business - he had all of that down - but Hendrix transcended his instrument.

I don’t think Jimi Hendrix thought about playing guitar as a guitar player, otherwise he wouldn’t have played like he did

“The Star- Spangled Banner is, I think, the pinnacle of electric guitar playing. It’s a monstrous performance at Woodstock. I can’t think of anything that’s been said that’s more poignant in so many ways politically, as well as sound-wise. The Vietnam war was happening at the time and y’know, that sound: it’s like napalm bombs and machine guns and planes and helicopters, and there’s all that, ‘The Star-Spangled Banner? Fuck you!’ That’s what it was about. It’s like free jazz playing. You can hear John Coltrane or Eric Dolphy or Ornette Colman - it’s all in there. He’s got a tune that he’s playing and then he’s right off into somewhere else and then back to the tune again. It’s not about guitar being played in a conventional way.”

Is that something you aspire to?

“That’s one of the joys in playing guitar, or any instrument. It’s more difficult in an orchestra - playing Mahler you can’t cut loose - whereas the world we inhabit doesn’t have boundaries. It’s funny how we tend to restrict ourselves. Y’know, ‘I want to sound like this’, or, ‘I wish I could be like Muddy Waters’. But those guys were making it up and moving things on.”

Is there any uncharted territory left in the guitar world?

“You follow your heart, don’t you? It’s about musicality. It’s like The Star-Spangled Banner - thinking beyond what the instrument is. I think there is lots to be done. For me, playing guitar in a very typical way holds no interest at all. You could argue that there are very popular songwriters out there, but it’s very conventional in many ways. What I’m doing now will probably sell about nine copies, but I’m happy with that. It’s all right. Some of it will filter into new Portishead things, because I’ll just use what I’ve got in my head (if it’s relevant).

“It’s not wilful desire, it’s just a kind of looking forwards and looking into what could be. Playing guitar can be so many things. It’s been my salvation, my way of making a living, my self-esteem, my friend, my everything, through all those years of darkness and light. It’s a private thing as well as a public thing. You develop a relationship with it.”

Rod Brakes is a music journalist with an expertise in guitars. Having spent many years at the coalface as a guitar dealer and tech, Rod's more recent work as a writer covering artists, industry pros and gear includes contributions for leading publications and websites such as Guitarist, Total Guitar, Guitar World, Guitar Player and MusicRadar in addition to specialist music books, blogs and social media. He is also a lifelong musician.