“They said, 'how can you possibly do this, Brian?' I said, 'something got inside of me - I had to do something'”: Unpicking the Beach Boys' classic that confirmed Brian Wilson’s creative genius

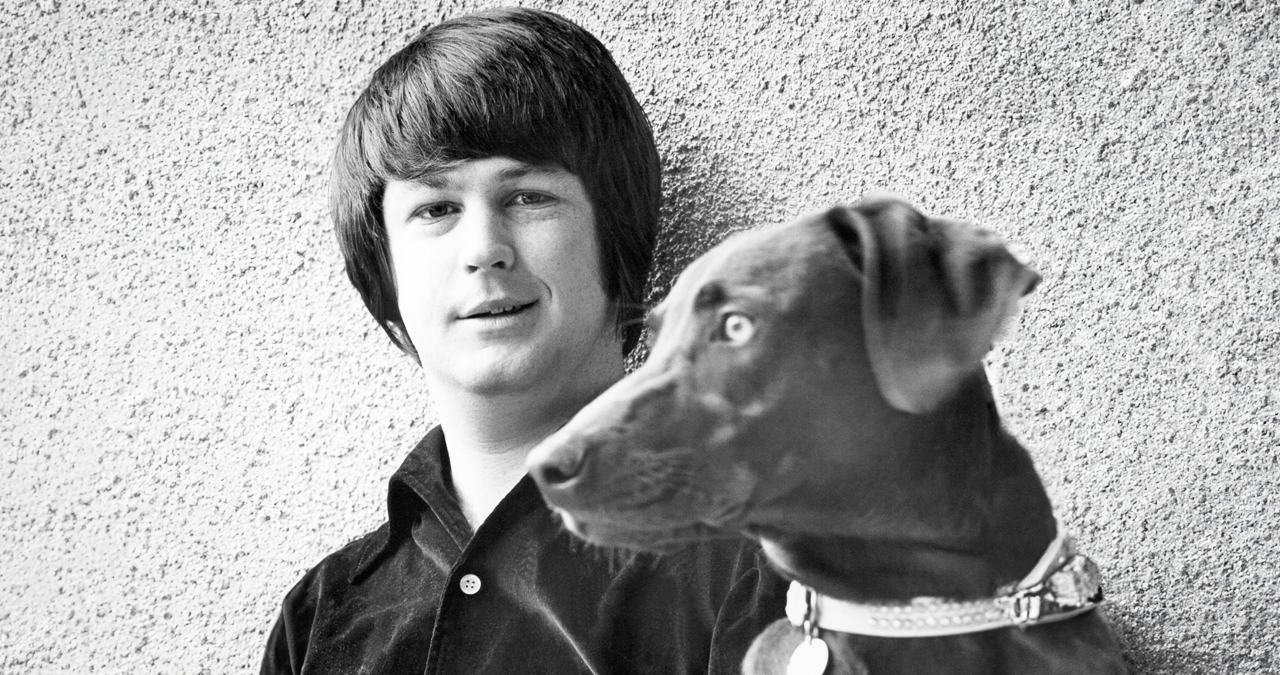

Conceived as an all-in-one ‘pocket symphony’, Good Vibrations was thematically triggered by the notion that dogs could sense the positive or negative energies of humans

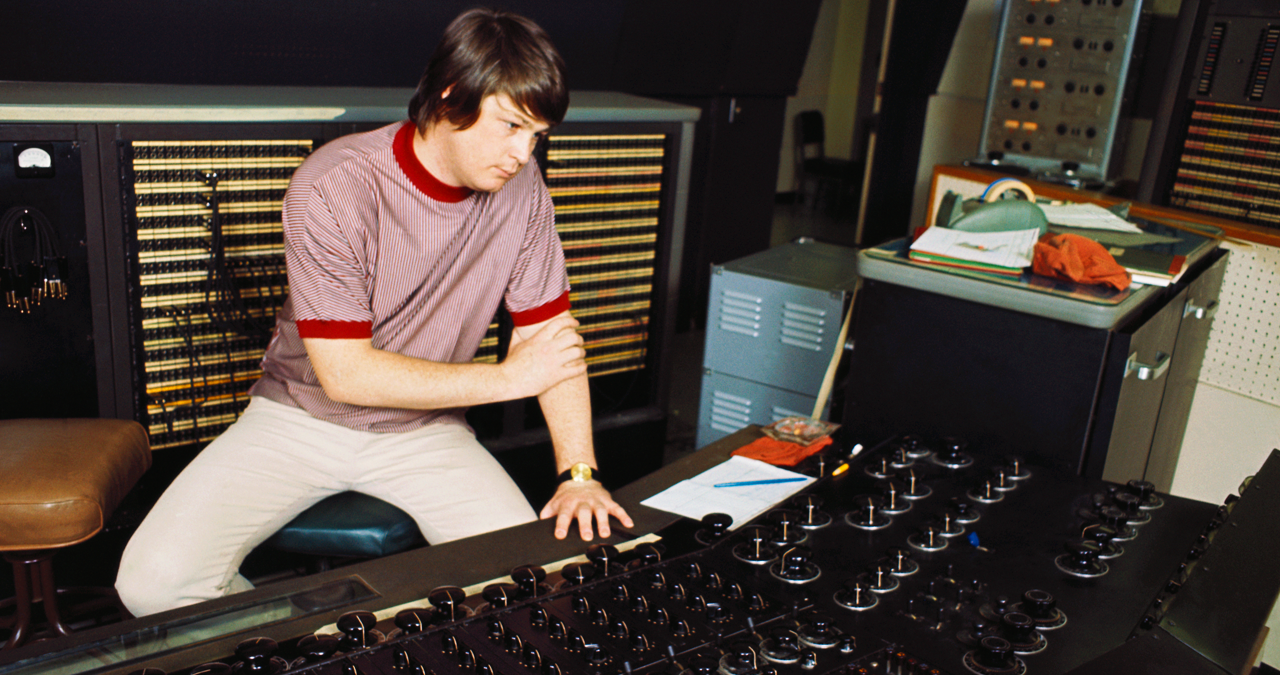

The recent death of Brian Wilson was a real gut-punch to to us here at MusicRadar. The visionary architect behind so many of our favourite ever records - and the man who pioneered the notion of the studio as instrument - Brian left us all a bountiful legacy of music that still feels timeless today.

It’s only right, then, in this period of mourning the loss of such a musical titan, that we should take a closer look at perhaps the grandaddy of them all. That one Brian Wilson masterwork that perfectly encapsulates the man’s elemental alchemy, technical prowess and musicological genius. The Beach Boys’ 1966 jewel, Good Vibrations.

Penned amid the creatively plentiful Pet Sounds sessions (but not finalised until that record was released), Wilson's starting point for Good Vibrations was to map out what would be the pop equivalent of a standalone symphony, with numerous different sections.

On the heels of the lavish Pet Sounds, Good Vibrations would further signal the artistic boundlessness of California’s former surf-rock champions like no other song.

It would also firmly establish their chief creative lynchpin as the radical musical pioneer of the 1960s. A position that we're sure even the Beatles would agree with.

Good Vibrations wasn’t born in a vacuum, the will to even attempt a track this weird was spurred by the increasingly adventurous musical direction the Beach Boys were already heading down.

The five men had come a long way since forming only a handful of years prior in 1961. Brian had founded the group alongside his brothers, Carl and Dennis, as well as their cousin Mike Love and close friend Al Jardine.

Awed by the soul-touching sound of harmony group, The Four Freshmen, Wilson’s first feat of meticulous musical assembling was getting his brothers to vocally lock-in with him; “We weren't copying the Four Freshman," Wilson later said, "I learned to give the guys parts to sing from the Four Freshmen. The guys took to it very easily.”

Get the MusicRadar Newsletter

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

The quintet had gone on to find international fame via their infectious, life-affirming brand of surf rock - then quite the coolest genre of pop.

It did much to transmit the halcyon Californian dream of carefree, permanent summer days to the wider world. Days where the only concern was catching waves - and girls.

Though sticking to a rigid formula, hugely popular early cuts such as Surfin’ USA, I Get Around and Surfer Girl showcased the five’s penchant for impeccable vocal harmonising.

Increasingly being directed by their fastidious leader and principal songwriter, Brian Wilson, the Beach Boys soon tired of the breezy guitar-pop formula - and its adjacent fixation with surfing.

“I wasn’t into surfing at all,” Wilson told Uncut magazine in 2006. “My brother Dennis gave me all the jargon I needed to write the songs. He was the surfer and I was the songwriter. Capitol encouraged me to keep on writing surf songs. I just wrote and wrote. I didn’t want to quit while we were ahead.”

But a timely panic attack brought on by the stresses of touring resulted in Brian deciding to step away from Beach Boys’ demanding live duties in late 1964.

Instead, Brian would remain in-studio, and be freer to focus solely on his primary passion: expanding the band’s musical universe for their next chapter.

A rapid release rate of studio albums across 1965 (The Beach Boys Today, Summer Days (and Summer Nights!!) and the ‘live party’-themed Beach Boys Party!) were propelled by both Wilson’s increasingly prolific nature - and the commercial demands of the band’s label, Capitol.

1966’s Pet Sounds changed everything.

Conscious of pop music’s burgeoning intellectualism and triggered by a semi-spiritual awakening brought on by heavy pot smoking and LSD use, Wilson’s perspective shifted.

With one eye on the inventive songwriting of the Beatles and with the newfound abilities of studio technology (as well as innovative production techniques in the air, such as Phil Spector’s ‘Wall of Sound’) - Wilson began to believe that anything was possible.

Audacious ideas started to brew.

A feat of unbridled inventiveness, Pet Sounds was Brian Wilson’s magnum opus.

Firmly established as the band’s creative director, Wilson oversaw the recording of his bandmates and brothers between four separate studios, working tirelessly on a plethora of songs that went far beyond the typical early Beach Boys fare.

Incorporating a wealth of instruments not typically used on a rock record (french horn, harpsichord and tack piano to name just three), and enmeshing vocals and found sounds alongside a troupe of session musicians (the legendary Wrecking Crew), Brian conducted ever-complex arrangements.

At this moment in time, Wilson (who was notably deaf in one ear) had become preoccupied with the idea of music production becoming ‘modular’ - that is having verse, chorus and bridge-sections which could be dragged around and slotted in different parts of an arrangement. That's a standard practice in today’s slick DAW-based world.

Such an approach might seem like and obvious and inevitable evolution of music production, but it was a truly groundbreaking approach in the mid-sixties.

At that time, straight recordings of bands playing their songs within the studio during a session was still the order of the day - perhaps with a handful of later overdubs to pad out the arrangement.

As you can imagine, moving musical information around like this in the pre-computer, pre-digital age was a feat of trial and tribulation - it required painstaking attention to detail, and steady hands.

The analog 4-track tape recordings had to be cut and spliced together using razor blades, tape-splicing blocks and adhesive tape. Delicate fingers - and an awareness of precisely what the music was doing at the millisecond you were splicing - were essential for successfully assembling a song.

It was a hard and potentially destructive process. It often required the creative use of effects (such as long reverb-tails) to hide harsher splices. But in working to realise his extraordinary visions, Brian was laying the foundations for everything that followed.

Though Pet Sounds was critically venerated, and contained some of the Beach Boys’ most beloved work (God Only Knows, Wouldn’t It Be Nice, You Still Believe in Me, etc) it was another song - which first bubbled up during the Pet Sounds’ sessions - that would fully underline Wilson’s new position as the world’s most innovative music-maker.

Still on something of a spiritual (and substance-infused) kick, the 23 year-old Wilson became preoccupied with the ‘vibes’ of certain chord sequences.

Wilson’s newly attuned vibe-radar caused him to recall how his mother would advise him, when encountering barking dogs during his youth, to not feel scared as dogs could ‘pick up the vibes.’

“I didn’t really understand too much of what it meant when I was just a boy. It scared me, the word ‘vibrations’”, Wilson was quoted as saying in Keith Badman’s book, The Beach Boys. “She told me about dogs that would bark at people and then not bark at others, that a dog would pick up vibrations from these people that you can’t see but you can feel.”

The musical foundations of the song that alluded to this extra-sensory perception, Good Vibrations (initially known as ‘#1 Untitled’), started as a piecemeal assemblage of musical ideas that was periodically tinkered with during the Pet Sounds’ sessions.

“I wanted something with real merit to it, artistic and smooth,” Brian told Uncut. “Some people say it was written on acid. But I don’t accredit it to LSD, I accredit it to marijuana.”

But Brian wasn’t the only Beach Boy with significant creative input, Mike Love penned the apt lyric, expanding on an initial draft by collaborator Tony Asher.

“This was before the Summer of Love, but there were definitely psychedelic rumblings on the West Coast,” Love told Uncut. “I felt Good Vibrations was the Beach Boys’ psychedelic anthem or flower power offering. So I wrote it from that perspective.”

Over a six-week period, Wilson guided the band around the various modular sections of Good Vibrations between four different studios (Gold Star, Western Recording Studios, Sunset Sound and, for the bulk of vocal tracking, Columbia Studios).

As with Pet Sounds, the close harmonies and backing vocals were a pivotal texture.

As Al Jardine recalled in an interview with Uncut; “Brian was absolutely at his peak back then. God, he was just like a freight train. We were hanging on for dear life. The Beach Boys were in and out of the studio day and night. We’d been busy touring Japan while Brian was composing it. We didn’t have much time to rehearse, so we just went for it.”

Coloured by a rich confluence of musical elements, the genre-shunning structure of Good Vibrations shifted between its slower-paced, dreamier verse (with a lead vocal sung in fittingly opiated fashion by Carl Wilson) a galloping gear-shift into a faster-paced chorus and a swelling bridge, before the entire song fell away and re-situated the listener amid a deep, soulful organ. Suddenly, a final vaulting chorus led the track home.

Navigating the unconventional piece proved tricky, particularly considering its ever-fluctuating tempo - and the fact that it had upwards of 14 (!) key-changes, as we'll talk through…

That floaty verse is grounded in a Eb minor key (and a I-VII-VI-V chord progression). As the verse reaches its conclusion, a pace-setting return to the root chord (Eb minor) helps to modulate the key to Gb Mixolydian (key-change 1).

As the chorus progresses, the key ascends (smoothened by the lush harmony vocals) upwards to Ab Mixolydian (change 2), then, reaching even higher, the key shifts further to Bb Mixolydian (3), before landing back on the safe, stable home ground of the verse’s Eb minor key (4).

The same verse and chorus key-changes repeat (and the key therefore changes a 5th and 6th time) but instead of heading back on Eb Minor, the chorus bleeds into a less anchored (and reverb-soaked) bridge now staying in the key of Bb Major (7).

Plateauing the listener in the chorus's heavenly pinnacle, suddenly Wilson opts to strip everything away.

As the clouds fade, we’re suddenly bathed in the warmest organ you’ve ever heard - operating in a pulsing F Major (8).

As this bridge section (surely a strong contender for the most divine piece of music, ever made) reaches its tip, another gear-shift occurs.

Abruptly swinging us into the final chorus at what was previously its highest part (Bb Mixolydian - the 9th key change), the effect is as if we’ve just crashed back down to Earth - but with newfound spiritual oversight.

Wilson tunes us back into another level of consciousness, taking the elevator back to the floor of the song where that chorus has been jubilantly rolling along the whole time, while we’ve been away, basking in that soul-caressing organ-bridge.

Moving in a reverse direction this time, the last chorus key steps down to Ab Mixolydian (10), then rumbles around Gb Mixolydian (11) before clicking back into to the initial upwards direction of the first couple of choruses, getting back to Ab Mixolydian (12), Bb Mixolydian (13) and then remaining on Ab Mixolydian for the Electro-Theremin-dominated final hurdle. That’s the 14 key changes.

What’s extraordinary is that this number of shifting sands works incredibly well.

Even when the changes jarred (as it sort of does when switching out of the organ and back into the final chorus) they jarred with creative and thematic purpose.

“I thought the tempo changes and chord changes were amazing. To this day, Brian has a wonderful sense of chord structure that baffles my mind. No one else sees it the way he does,” said Al Jardine to Uncut.

The characterful theremin sound that crops up throughout Good Vibrations' choruses was in fact not a 'real' theremin, but an electronic variant developed by Paul Tanner and Bob Whitsell.

This Electro-Theremin - actually played on record by Tanner himself - could produce a pure sine wave ranging between three to four octaves, and a knob enabled him to oscillate its tone naturally across a key-bed, giving the sound its eerie, sentient quality.

Previously deployed on sci-fi soundtracks (or pop songs which allude to space), the Electro-Theremin's inclusion here added a suitably interplanetary effect.

Though legendary Wrecking Crew bassist Carol Kaye was instrumental in developing Brian’s free-range, walking bass ideas throughout the track, some Beach Boys archivists have claimed that the final recording of Good Vibrations substituted Kaye’s performance for Lyle Ritz on double bass and Ray Pohlman on electric bass.

But, as she told us in 2011, Kaye firmly believed her hard-plectrum-plucked bass recording was used in the final edit; “I played just what [Brian] had written out. There's string bass, too, but you don't really hear it. What you hear on the radio is me on my Fender Precision - that's what Brian wanted me to play.”

Assembling all Good Vibrations' disparate parts captured at the four different studios, Wilson tape-patched the individually recorded sections together. He paid little mind to the eye-watering bill he'd racked up to pay for this unregulated studio time.

In fact, Good Vibrations ended up being the most expensive single recorded at the time, with the final figure being between $50,000 to $75,000 - the equivalent of $400,000 to $600,000 in today's money.

Assisting the tireless Brian with his tape-splicing was engineer Chuck Britz, who remembered “[Good Vibrations] was his whole life performance in one track. A harmonic convergence of imagination and talent, production values and craft, songwriting and spirituality.”

Once it was finished, Wilson gathered his bandmates and played them the final edit.

Their jaws dropped.

"They were very blown out. They were most blown out. They said, 'Goddamn, how can you possibly do this, Brian?' I said, 'Something got inside of me - I had to do something,’” Wilson told NPR. “They go, 'Well, it's fantastic.' And so they sang really good just to show me how much they liked it. They sang for me."

Released in the US on October 10th 1966 (and in the UK on November 2nd) it was obvious to many that the Beach Boys had just set the bar extremely high for the nascent psychedelic pop genre.

While some were initially skeptical of the sheer oddness of the track, its beauty was quickly recognised.

Initially landing at the lower reaches of the Billboard chart, word of mouth and radio play set the track rocketing upwards, eventually reaching the top spot in both UK and US.

Good Vibrations has, of course, subsequently been rightly recognised as one of the greatest pop songs - and pieces of music - of all time.

Wilson had intended to build on the creative strategies deployed when making Good Vibrations with a 12-track concept album, entitled Smile, but the project was derailed due to Wilson's growing struggles with a schizoaffective disorder, coupled with record label-wrangling.

The Smile project was shelved indefinitely. Though an inferior, cut-back version - Smiley Smile - was released (and a re-recording of some of the record's ideas was put out by Wilson in 2004) the original, eternally tantalising, Smile record remains forever lost.

The impact of Good Vibrations on popular music, however, was immense.

Wilson’s purple patch notably had a profound influence on the Beatles, who had switched to emulating Brian Wilson’s permanently in-studio approach by 1967. An approach that resulted in their monumental Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band in the summer of that year.

It was an influence that the Beatles’ producer George Martin was all too conscious of, as Giles Martin - the son of the Beatles’ producer, George Martin - remarked to this writer in an interview around an Atmos reissue of Pet Sounds, “I was with my dad on a plane once, and I just suddenly realised how awesome he was. I said to him ‘Dad, what you did with the Beatles was kind of amazing, wasn’t it’ and he looked at me and said, ‘not as amazing as Brian Wilson.’”

I'm the Music-Making Editor of MusicRadar, and I am keen to explore the stories that affect all music-makers - whether they're just starting or are at an advanced level. I write, commission and edit content around the wider world of music creation, as well as penning deep-dives into the essentials of production, genre and theory. As the former editor of Computer Music, I aim to bring the same knowledge and experience that underpinned that magazine to the editorial I write, but I'm very eager to engage with new and emerging writers to cover the topics that resonate with them. My career has included editing MusicTech magazine and website, consulting on SEO/editorial practice and writing about music-making and listening for titles such as NME, Classic Pop, Audio Media International, Guitar.com and Uncut. When I'm not writing about music, I'm making it. I release tracks under the name ALP.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.