Objekt: "The world would be a boring place musically if everyone knew exactly what they’re doing"

Ingenious producer TJ Hertz resumes his longstanding white label series with Objekt #5. Danny Turner charts his innovative approach to tech

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Berlin-based DJ/producer TJ Hertz began his musical life as a drummer prior to joining software manufacturer Native Instruments as a DSP engineer. Although already recording as Objekt, the role had a circular effect on his music-making process, enabling him to showcase an audacious production style that has mesmerised both club-goers and audiophiles alike.

Hertz’s struggle to record Objekt material on a consistent basis has, ironically, added a sense of renewed anticipation with each release. Since his debut white label Objekt #1 in 2011, it’s taken over a decade to reach a fifth instalment. However, Objekt #5 merely solidifies Hertz’s reputation as one of the most vital and progressive electronic artists.

Did you always possess a technical approach to production?

“When I first started making electronic music I was mostly playing drums, bass and guitar in bands and recording amateur-hour stuff on the side. I had cracked copies of pretty much everything, but started with Sonar and Cool Edit Pro before moving on to Cubase and a bunch of other stuff.

“My mum was a professional composer in Manila for many years and did a couple of scores for Filipino films, some library music and a bunch of jingles, so before I started making electronic music I used to play around in her studio. I didn’t make anything particularly ground-breaking, but bearing in mind this was the ’90s and the studio was older than that, I was able to record stuff on the piano roll of her Atari ST and play back instruments on her sampler and a few sound modules. For a 16-year-old, I suppose I had a fairly advanced knowledge of how hardware and mixers worked.”

Your early releases seemed to gain quick recognition from your peers…

“The first few years of my artist career were quite bewildering in terms of how quickly the stuff I was making seemed to get an appreciative audience with some of the artists I admired the most. I remember my agent telling me that he’d passed my record on to Aphex Twin who liked it and began playing it out. Autechre were also one of my biggest inspirations. I met them a couple of years later and they were very supportive.”

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

Was there any value in trying to figure out their music-making methods?

“I picked up bits and pieces of information and was interested in trying to figure out how they made certain things, but I was never a super hardcore IDM production nerd. To be honest, I don’t listen to a huge amount of dance music. In fact, before lockdown I felt that my relationship with music was becoming increasingly functional and found it harder to listen to music for enjoyment’s sake, but by the end of 2020 I got better at switching off the part of the brain that wonders how something is made or how my own productions stack up to it.”

With so much technology available, do you think that it’s getting increasingly difficult to figure out how a piece of music was made?

“It’s something I’m always curious about when I hear a sound that’s unidentifiable to me, but recently I’ve grown increasingly comfortable with not knowing. There’s so many different ways of generating and processing sounds that even if you had the same tools at your disposal as the person that made a piece of music, the relationship between the sound that comes out of their signal chain and the various parameters they have at their fingertips is so wildly unstable that it doesn’t necessarily make sense to try to recreate it.

I’ve started to question the point of caring too much about how someone else’s record was made

“Personally, I’ve got so many wildly unexpected results from synths and effects that I wouldn’t have attributed to the sound in my head that I’ve started to question the point of caring too much about how someone else’s record was made. Right now, I’m more interested in what’s an interesting tool chain to play around with and seeing what comes out of that.”

How did you get a job working as a DSP engineer for Native Instruments?

“I studied information engineering with a specialisation in electronic engineering, stuff like signal processing, image analysis and a bit of machine-learning. Native Instruments was my first job out of university in 2009 and the role was for a DSP software developer but I didn’t really know what I was applying for at the time.

“I knew that NI were based in Berlin and I wanted to move to the city, so I looked at the jobs available on the website and applied for all of them [laughs]. I just think that they that saw a kid who was very passionate about wanting a job and didn’t really know if he’d be good at any of them, but were prepared to find out. It was a very different time.”

How has your role developed there?

“At the beginning I took a crash course in DSP engineering. I already understood a lot of mathematics and theoretical stuff, but didn’t really know how to code a plugin or write an audio algorithm. A lot of the effects that NI were developing at the time were prototyped in Reaktor, but they didn’t want to use Reaktor code in the products themselves so it was my job to port them to C++.

“That was a pretty good learning exercise because it gave me an inside look into what’s going on inside a plugin in terms of how it’s configured and initialised and the steps you have to take to avoid certain artefacts. Later on, I redeveloped the time code signal processing receiver for Traktor and implemented a bunch of drum synths for Maschine, but my role now has pivoted from mostly doing DSP work to machine learning research as applied to audio. I’m currently working on ML algorithms for audio processing and generation.”

How might machine learning be applied to a piece of VST software, theoretically?

“Let’s say you want to emulate an analogue circuit by making a clone of an 808 or a certain guitar amp that runs completely natively as a VST, the more conventional approach would involve going through circuit diagrams and analysing the circuits in order to replicate their behaviour in the digital domain through a variety of mathematical tricks.

My working style is something I’ve gravitated towards because I like to have a high degree of control and understanding of the tools I use

“The process is extremely long-winded, error prone and doesn’t take into account idiosyncrasies in the circuit design and components that can’t always be accurately modelled by the equations that you would normally use to describe what’s happening in a certain filter circuit. For context, it would normally take a couple of months for one highly skilled person in the art of analysing a guitar amp to create a digital model of it, which may or may not sound that much like the original because that stuff is quite difficult to model analytically. ”

How does machine learning help simplify that process?

“For simplicity’s sake, the ML approach treats the circuit as a black box. Essentially, there’s a signal processing algorithm that sits in the middle trained as a machine learning model that’s given a lot of input and corresponding output data. For example, the input data might be a bunch of test signals that you’d send through an amp and the output data would be the signal that you’ve recorded coming from that input signal.

“You do a bunch of magic and the ML black box model ends up with an algorithm that will replicate the process that takes you from input to output. It’s a gross simplification but, theoretically, you send it off to the cloud and then it’s possible to get a decent model of a guitar amp trained within a few days. The latest version of Guitar Rig has amplifier models in there that were developed completely by machine learning.”

How did working at NI feed back into the music you were beginning to make at the time?

“I wouldn’t say it had an influence on the sound but it definitely had an influence on how I approached the tools I was using. I was pretty technically well-informed in terms of knowing what each plugin I used was actually doing, but working for NI not only instilled a healthy sense of technical good practice but also scepticism in what different bits of equipment could or couldn’t do. These days there’s a lot of gear fetishisation, so it helps when you’re trying to figure out how much of that is legit or marketing bullshit.”

For your Objekt productions, is it of vital importance to understand the inner workings of a piece of software?

“It’s absolutely not necessary. My working style is something I’ve gravitated towards because I like to have a high degree of control and understanding of the tools I use, but I don’t think by any means that it’s the be all and end all of how music should be made. Some of my favourite music has an immediacy to it that comes from an element of lack of control, abandonment and irreverence, and the world would be a boring place musically if everyone knew exactly what they’re doing.

The world would be a boring place musically if everyone knew exactly what they’re doing

“Some of the most exciting music that’s ever been made is by people winging it with a sense of youthful exuberance. The start of my creative process is often about generating unpredictable results and finessing them from there, whereas others get closer to where they want to be from a much earlier stage. For me, it’s becoming increasingly important to not have complete control over a situation; otherwise what comes out is going to sound really sterile.”

During the initial creative phase are you driven by concepts and projecting outwardly from there?

“Not explicitly. I have sometimes made music that way, but I don’t usually have an overarching top down vision or inspiration in mind. The creative process itself often throws up ideas and associations that connect. For example, if I’m working on a passage in a track and it’s evocative of a real-world scenario I might lean into that, but I don’t know if I’m aiming for anything specific from the outset. Hopefully, the music I make elicits some kind of emotional response. It might not be heartfelt or austere, but there needs to be an element of sincerity because that’s the thrust that gives a piece of music something worth listening to.”

If we take your Objekt #5 single Bad Apples/Ballast, how did you approach the design of those tracks?

“I don’t have any tried and tested workflow for churning out new ideas. Quite honestly, it’s different every time I go into the studio, which is probably why I take so long to release music. I also don’t have very much studio time because I either have the day job or I’m touring a lot, so I’m not going in several days a week, every week. So to answer your question, in those early stages I spend quite a lot of time just flailing [laughs], but I’ll try to begin with a sketch that I was trying to push in a particular direction where the only element that’s worth developing is one that takes the next stage of the track into a completely different creative zone.

I never actually throw anything away. I religiously save every incremented version of everything that I’m working on

“That was actually the case with Bad Apples, which started as a very melodic, almost poppy, dancefloor track. It had a bridge with a synth playing the arp that later became the bassline. I made the sketch one afternoon; it wasn’t very good, so I came back a week later and thought, this kind of sucks but that particular arp is kind of cool and I can imagine it being played on a bass guitar, so I went into my sample library and followed my nose from there.”

Do you have to rely on intuition to tell you when a track’s finished?

“Once I’m past the sketching stage and throwing ideas at the canvas I’ll always open up the bounce from the last session, listen to it – ideally in iTunes, make notes and timestamp whatever needs changing. That could be something as major as getting rid of a whole section to a new bassline or something minor like there’s a little bit too much frequency on the snare.

“Once I have half a page of notes on what I want to change, I’ll go into the DAW project and be pretty strict about only changing the stuff I’ve written down. Once that’s done, I’ll bounce another copy and start the whole process again until I get to a point where the notes are essentially negligible. Then I know the track is done.”

If you come back a week later and it still doesn’t sound right will you start unravelling it?

“One of my problems is that a lot of the time I end up prematurely optimising a track and trying to make it sound good before I’ve got all the elements in there. At that point I won’t have any notes left but for some reason the track doesn’t feel very good, in which case I’ll usually discard it and come away from the session feeling pretty horrible.”

Either way, it sounds like taking time away from the track and returning with fresh ears is one of the most important things you can do?

“Coming back with fresh ears is absolutely critical, but I don’t think having limited studio time is. A better way to ensure you come back to a track with fresh ears is to work on several different ones at any given point and rotate them over the days that you spend in the studio. If you only have one studio day every two weeks then you don’t get into a flow and forget the tricks you learnt from previous sessions. When that happens, having slow output becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy.”

Is anything truly discarded or will you bank ideas that can potentially be repurposed later on?

“I never actually throw anything away. I religiously save every incremented version of everything that I’m working on, but I definitely burn out on tracks and don’t want to hear them again for months or years. Sometimes I go back to them and strip out a sound or think there’s a little mileage in it, but I wouldn’t say that my albums are an outlet for my more mediocre production stuff. I’d never think this track isn’t good enough for a single so I’ll stick it on the album towards the tail end and hope people don’t notice.”

You mentioned Ableton earlier. Are you using that to record from conception to completion?

I’m 95% in the box and Ableton is definitely my workhorse

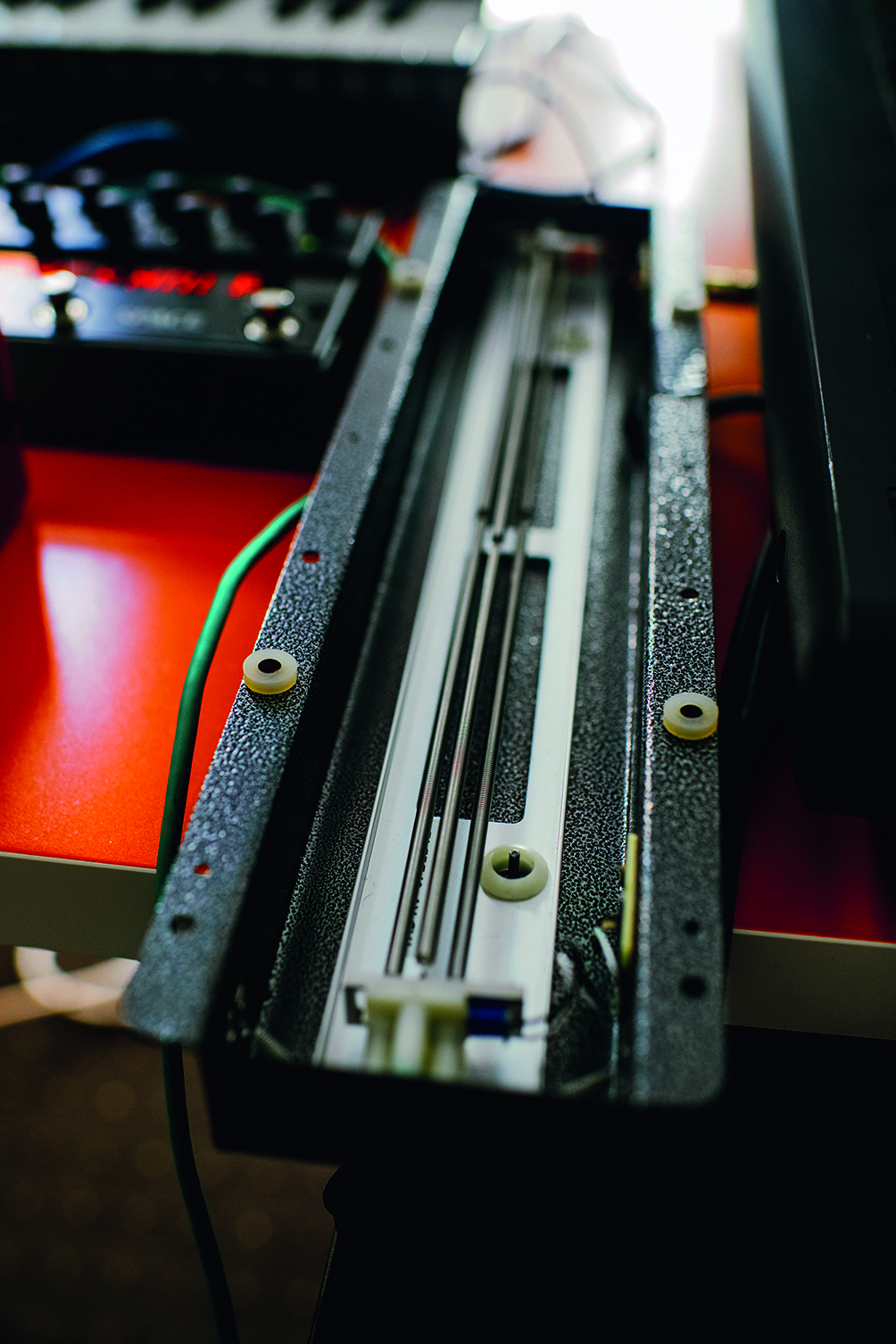

“I’m 95% in the box and Ableton is definitely my workhorse. I do have a bunch of outboard synths and effects, which I don’t use very much, but when I do they’re quite important to the creative process. Sometimes it takes getting out of the box to trigger a certain improvisation that will propel my workflow forward, even if the sound itself doesn’t feature all that heavily on the finished product.”

So you feel it’s important to get out of the box once in a while to allow hardware to feed your creativity?

“Getting hands-on with stuff, recording the result and then resampling it, is a lesson that I often have to learn the hard way. Instead of drawing automation on super-long signal chains, I’m better served by keeping it simple and recording stuff by hand, bouncing the result to audio and loading it back into a sampler or playing around with a live warp engine. So many of my more interesting results come from processes like that, but I often forget to do them.”

Which of your hardware tools help with that approach?

“On my last album, I used a table top semi-modular synth called the Reon Drift Box a lot and recently bought a BugBrand PTDelay, which has a very well-known IC delay chip that was used in all sorts of iconic delay pedals. On the boutique version, the gain staging is set up in such a way that you can distort it in quite creative ways and get some extremely crunchy, weird and warped sounds, so I don’t use it much as a delay but more as a sound effects generator.

I’ve been playing around with a very old, cheap spring reverb unit. It cost about £20 and isn’t even really a spring reverb – it’s just the spring and an exposed pickup

“Recently, I’ve been playing around with a very old, cheap spring reverb unit. It cost about £20 and isn’t even really a spring reverb – it’s just the spring and an exposed pickup. I basically plug it into a preamp, scrape and tap on it and run it into the PTDelay to create these really unholy-sounding, clanging metallic sounds that are really gritty and resonant.”

And from there it all ends up in Ableton for mixing and post-production?

“Ultimately, it all ends up in Ableton where I use stock plugins for dynamic processing, mostly the Eventide Omnipressor or Native Instruments’ Transient Master. Unsurprisingly, I use quite a lot of NI stuff like the Replika delay, Monark VST or Crush Pack, which is made up of three VSTs for distortion and mangling and the bitcrusher is really good. I like Freak as well because it has a really cool radio modulator that’s quite pretty sounding. I also use FM8, Razor and Omnisphere for a whole bunch of things and some of the Arturia stuff, like the DX7 emulator.”

Are you analysing sound as a visual spectrum and calculating how frequencies respond to each other?

“I try to maintain some sense of perspective. Ultimately, if you can’t hear the difference it’s not worth worrying about too much, but I do use a lot of visual cues and these days I’m exploring Max for Live sequencers more by modulating quite extreme parameter changes and introducing a lot of randomness when sketching new material.”

How much control are you allowing yourself over various generative or algorithmic tools?

“If I ever use generative tools then it’s really just for the first step of the music-making process and the results would be mangled so much that I’m not too concerned about whether I wrote it or the computer did. Ultimately, it’s just an extension of how people use hardware sequencers to get a happy accident.

I’m interested in using generative tools in a live performance environment

“I haven’t explored the possibilities of full spectrum generative composition in the sense of designing a patch that will produce a finished piece of music, but it’s something that I could be interested in at some point. Right now, I’m more interested in using generative tools in a live performance environment because I’ve yet to figure out how I can put together a workflow that allows me to perform live in a similar way to which a track was written.”

So you’re trying to figure out ways to control certain algorithmic processes in real time?

“The desire is to design some kind of generative patch or setup where I’m controlling high-level semantic parameters and letting the algorithm deal with the rest. For example, I could have a Max MSP patch that generates music with a preconfigured architecture of oscillators, filters and sequencers, in which case it’s reasonable to expect that the live performance would sound, not identical to an album, but a variation of the same sort of music. The only problem is that if I want an album to be generative rather than manually sculpted and pieced together it would take a bit of a shift in terms of how I approach the recording.”

Now that we have a single, is there a plan for a third studio album?

“At this point, I’m just happy to be releasing music again and don’t have much album material saved up so it’s likely to be a while yet. I did make a few tentative forays into producing for pop artists and that’s definitely something I’m interested in, but haven’t quite found the right collaborator yet.”

What would inspire you about working in that genre?

“Part of it is about constraints – in the same way that writing dancefloor music is interesting because you can experiment within a framework. When you have a set of rules it feels more subversive when you bend them and sometimes it’s easier to come up with ideas that are a little more unexpected. The same can apply to working with a pop vocalist where the constraint is that the song comes first and everything else has to fit around that.

“That’s an interesting challenge and because you’re not placing yourself front and centre your identity can take a bit of a back seat. It remains to be seen whether I’m suited to going into a studio, jamming something out and having a result within a few days, because that’s not really how I work, but I like the idea of it.”