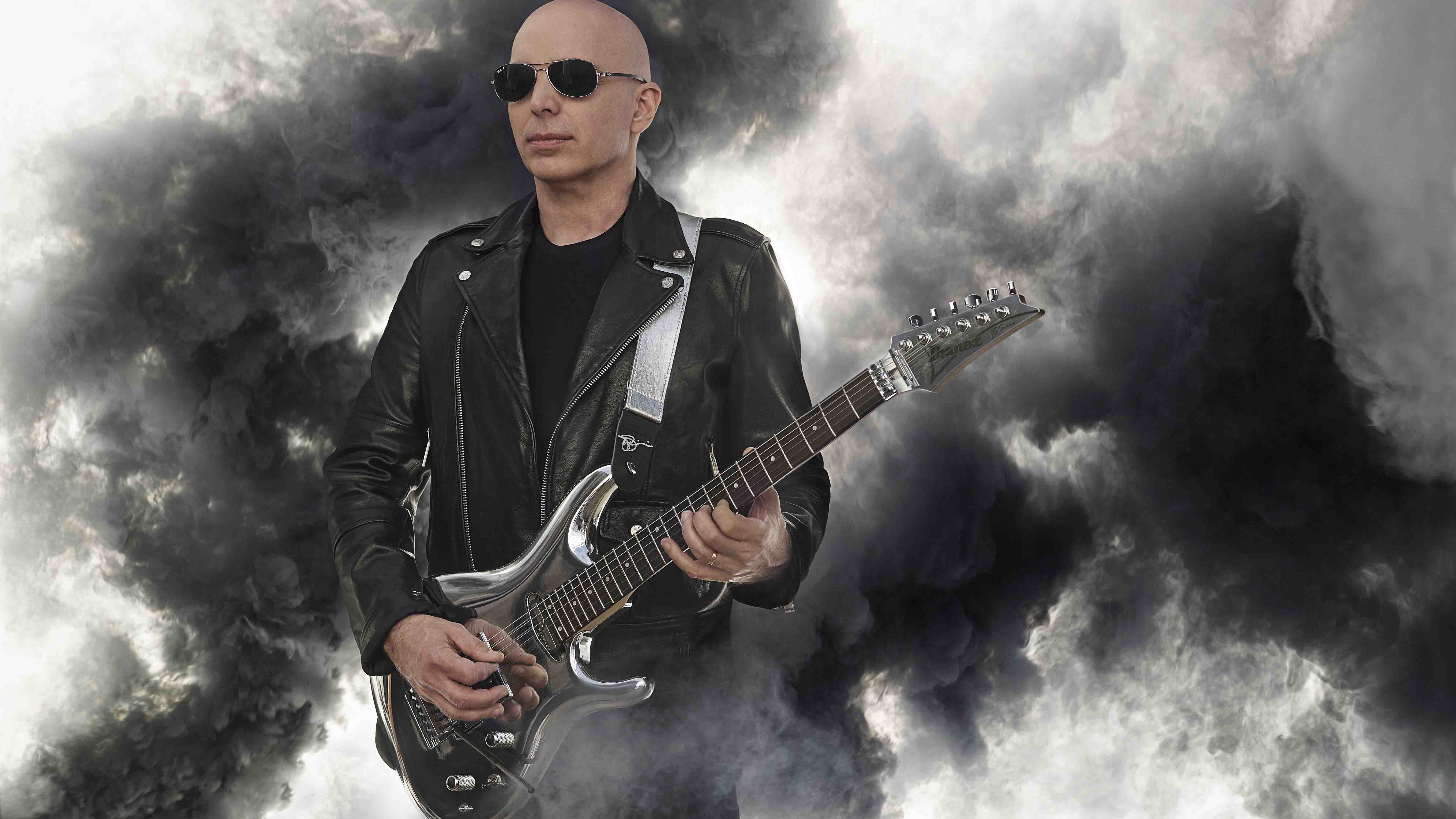

Joe Satriani's career in gear: "Don’t worry about Peavey vs Marshall; worry about what sets you free"

Shred sage shares essential electrics, amps and pedals from 30 years of instrumental guitar mastery

MusicRadar's best of 2018: With his countless Grammy nominations, tens of millions albums sold worldwide and a long-established stature as the biggest-selling instrumental rock guitarist of all-time, Joe Satriani is a musician that exists in a class of his own.

Today, he’s speaking to MusicRadar about the tools of the trade behind his most famous recordings and revered live shows - but not before offering some sage advice…

“It’s important to remember that all this gear is important to inspire us, but is less important when stacked against other things in the bigger picture,” reveals the guitar aficionado, calling from a hotel room while on tour with G3 across North America, which comes to Europe in April.

“If you like Fender, fine. If you prefer Gibson, fine… it really doesn’t matter. Don’t worry about Peavey vs Marshall; worry about what sets you free. That’s what people respond to: the spirit in the music and the quality of the writing.

“The average person doesn’t really care if your amp is from ’66 or ’68. Only guitar nerds do; we can all admit we get a bit crazy as total gearheads! But remember to use it to inspire yourself and put your spirit into the music. That’s what people want to hear… your spirit, not your gear.”

As usual, the legendary shredder makes perfect sense. Here, he talks us through his career in guitar and the equipment entrusted to bring that magical spirit to life…

Joe Satriani’s new album, What Happens Next, is out now via Legacy Recordings. Satriani brings G3 to the UK in April, featuring John Petrucci and Uli Jon Roth - tickets are available via Satriani.com and Ticketline:

Tuesday April 24 Southend Cliffs Pavilion

Wednesday April 25 London Eventim Apollo

Thursday April 26 Bristol Colston Hall

Friday April 27 Manchester Apollo Sunday

April 29 Portsmouth Guildhall Monday

April 30 Birmingham Symphony Hall

Boss DS-1 Distortion

“I love this pedal, mainly because its response to the guitar volume control is brilliant. The only problems it had was that it often would sound like you were stuck at 8.2 and couldn’t get to the extra push.

When you travel around the world with rented gear, having that one orange box that can get you through the gig is very important

“I felt it had a big bump at 100Hz and a high fizz content that was hard to dial out, which made it a bit anaemic when it came to full gain settings. It needed to be paired with an amp that’s clean and punchy but that can also carve out those two extreme EQ points.

“I always found any Marshall with a decent clean input would handle it well - back then, Marshalls weren’t known for a lot of low-end anyway. That was one saving grace. When you travel around the world with rented gear, having that one orange box that can get you through the gig is very important - though it’s worth remembering it’s still a substitute for a real amp.

“There’s nothing like a Marshall turned up really loud with all of its parts humming great… that’s still the best organic sound.”

DigiTech Whammy

“The most important thing about this pedal is that it extends your range, which is always fun. If you’re trying to create a signature for a particular song like Cool #9, where notes step out and do things that are unnatural. It can be a hook for an instrumental artist, which is a cool thing.

“I’ve used it not so much for harmonies but more unisons and octaves. Once in a while, I might use the chorus setting, but that was mainly for simplicity because it was easier than plugging in another pedal.

“One of the hidden plusses is that when you stack it up against all the other pitch-generating pedals - with the exception of the [Electro-Harmonix] POG and Micro POG - it appears to have the fastest processor. This is extremely important if you’re sending your signal into an amp that’s distorted.

“I just think for a quarter of the price, it really kills the Eventide pedals or any others that try to create a digital sub-octave. They have so much inherent delay it tears up the sound in your cabinet and ends up sounding like mush.

“I still use it - there’s a song on my new album [What Happens Next] called Catbot which is me trying to recreate software plugins. It did a much better job than anything else because of that processor. It’s a funny pedal… sometimes you never know what it’s going to give you, but it’s fun. It plays you like a wah-wah pedal does, which I like!”

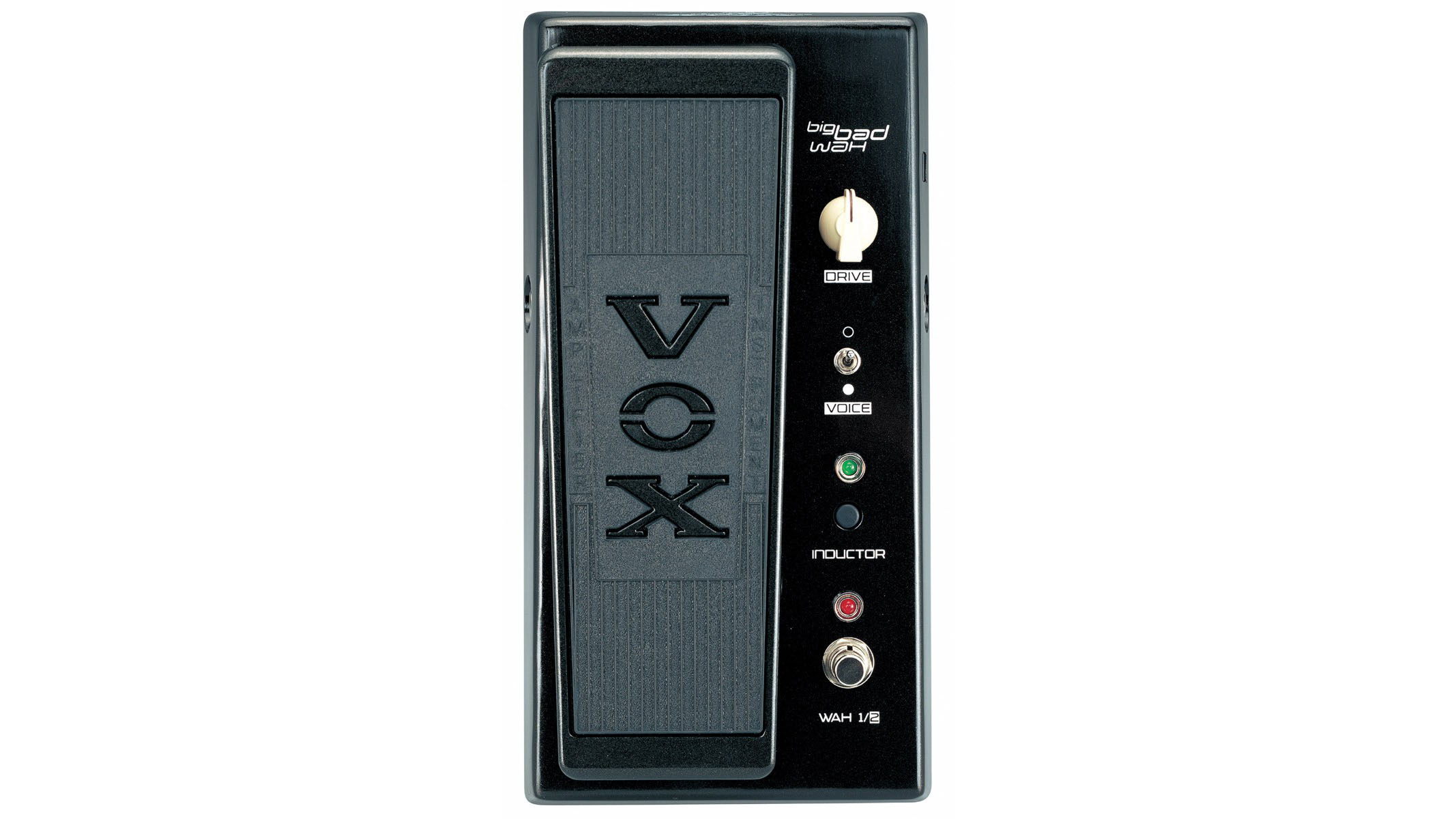

Vox Joe Satriani Big Bad Wah

“Before I had a deal with Vox, I owned a long string of Cry Babys. I found they worked well in conjunction with the DS-1, helping when you were plugged into a clean amp.

“But I began looking for a more vintage sound with a little something extra, so when the Vox deal came along, I took the original specs from the vintage wah and changed a few things in the crossover point lower in the mid-range. I always felt they would lose power there, so we were able to change that.

“It’s still my favourite wah-wah pedal because it has two potentiometers in there, the original Vox which I mainly use and one which is identical to a modern Cry Baby, which has a switch to get the really deep sweep. So it’s like two or three wahs in one, which is fantastic.

“I have more gain than I could ever use coming out of my Marshall amp, so it’s more of a classic setup for me these days.”

Vox Joe Satriani Ice 9 Overdrive / Satchurator

“I don’t use these at all any more. I think it was after the first Chickenfoot tour where I started using my signature Marshall prototype, and from then on there was no need for any drive pedals. I kinda like the idea of an amp that can do it all.

“To be honest, I don’t really like overdrive: the clean signal mixes with a distorted one and to me it always sounds like there are phasing problems no matter who is playing. I also don’t like having to run back and step on a pedal for a solo - I’d rather use my volume control on a more all-purpose setting.

“I’m pretty weird: I’m one of the few people that plays instrumental rock all the time, and my setup reflects that. It’s not like Kirk Hammett who plays rhythm and then needs to burst into solos; I know he relies on overdrive pedals to help get the midrange to cut through the massive sound of Metallica. But they’re coming from more of a scooped distorted sound.

“In order for me to play melodies that won’t kill you after two hours, I try to start with a softer sound that’s fuller. I can’t use a sound that will tear your head off for eight-bar solos in front of an audience all night long… it just won’t work. It shreds but it doesn’t sing and, to be honest, I’m singing most of the time when it comes to my tone. Both of these were cool pedals to develop… but I don’t really like them any more.”

Zoom 9002

“My song Cryin’ is a performance that was recorded live in one take through a Zoom handheld device. That was an unusual recording, for sure! If someone heard it on Spotify, they’d never think it was a live performance going into a handheld Zoom, through an RCA cable onto a 24-track machine.

“Why did we do it? We weren’t thinking… we were simply recording! The point I’m trying to make is that sometimes a $50,000 Dumble might not work, but a $150 Zoom thing could sound brilliant. It just comes down to your hands, musicianship and inspiration.”

Boss CH-1 Super Chorus

“I keep looking around for chorus and flangers; the last one I picked up was the Eddie Van Halen MXR signature. It has some outrageous sounds that make it a really fun pedal. Ibanez make some really nice old-school ones too…

“I’m not too crazy about that kind of modulation, but right now I have a Boss Super Chorus for that sound. I’m not using it much on this tour, apart from the song Circles which has a very clean, Stratty-sounding guitar.

I prefer a basic chorus, and usually end up bouncing between Boss and Ibanez. None of the others feel as demure as those two

“It was all done direct back then - we used a Songbird Tri Chorus, which was one of the first Bucket Brigade rackmount choruses back in the 80s. It’s a beautiful device - nothing in the pedal world comes close to it - but it couldn’t really be appreciated in stereo live; only a few people would be in the right position to get that. Upon realising that decades ago, I decided to think mono and not worry too much about stereo.

“I prefer a basic chorus, and usually end up bouncing between Boss and Ibanez. None of the others feel as demure as those two; they add that chorus sound without getting the way - which is really hard coming out of an amp that’s mic’d going through a PA… it can sound like a mess. I need a pedal that suggests just enough of it but doesn’t get in the way of your articulation.”

Fractal Axe-Fx II

“For the last few years, I’ve used an Axe-Fx II for all my delay processing. Before that, I used the Boss DD-2, and every time they came out with a higher number that was more reliable, I’d use it. There would be two running sequentially - one short and one longer to create a random cascading that would dissolve into almost a reverb sound.

“I did the pedal through the clean amp thing for a while, then I started using it in the effects loop and felt like I had run into more phasing issues. Effects loops do introduce a slight phase shift, and if you have a pedal that isn’t quite as efficient at passing the original signal, you get some cancellations.

The superior processing of the Fractal made me realise how much more of a dynamic sound I can get

“In a funny twist of fate, using the [Marshall] 6100 and DS-1, I was able to introduce phasing as a way to get rid of the 100Hz bump! But when I moved onto other amps, that particular wrong thing wasn’t available as an option. I realised I had to come up with a different solution.

“I tried using my Vox Time Machine delays, which were constructed really well, with full bandwidth return or vintage return with a ducked low-end under 60Hz, shelving high-end at 6K and above. It made for a lighter, more demure-sounding return that wouldn’t get in the way of your new notes but rather create an ambience behind those notes.

“It was the superior processing of the Fractal that made me realise how much more of a dynamic sound I can get. Not only can it mimic those EQ curves, but I can also eliminate any other phasing issues… it’s pretty remarkable. I use very little delay, but it’s there and I have a volume control for the return that I can use throughout the show - which is essential for the new material.”

Peavey JSX

“This amp had a lot of strengths; we were able to look at the clean and take the best parts of a Marshall 6100 and improve upon them.

“The sound of a Satchurator or DS-1 into the clean channel, with the amp cranked to 115dB was great - in fact, way better than the 6100. We recorded a lot of great stuff in the studio and live using that.

“I requested the crunch channel from the Peavey Vintage 50, because I felt like it was the greatest Peavey amp ever made. The designer, James Brown, was able to make it part of the JSX amp with some additional EQ curves.

“That sound is really something - on the song If I Could Fly, you can hear a very long extended solo. That’s where this amp really shined and sounded beautiful. That particular channel I think was the highlight of James’s career… it was very compressed but gorgeous sounding, with a classiness that was wonderful.

“The final channel I had little input on… you think you have all the time in the world to get things right, and before you know it, there are deadlines and you’ve released something that you feel is 90% there. The drive channel idea came from the Triple X, without some of that midrange, which I always felt was excessive for classic rock, though it still didn’t get used much. I’d use my Satchurator into the clean channel for my live performances.

“The cabinet had a speaker out that was post-power amp and would feed off the speaker… it was such a great innovation. Unfortunately, there were problems in manufacturing it. They didn’t take into account how much the cabinet would shake at high decibels, so they’d eventually go down just from the vibrations. If anyone sent phantom power into them, they’d get burned up.

“It happened on TV when I went on the Conan O'Brien show - they fried three of my cabinets in just two minutes! I guess the world just wasn’t ready for it...”

Marshall JVM410HJS

“That’s down to the genius of Santiago Alvarez, who was the main engineer that revolutionised Marshall over the last 10 years, though he’s no longer with them…

“We were trying to make a four-channel amp with choices for gain stages, so we looked at the original JVM and changed the gain structures radically, decreasing and increasing on different ones. We removed as much compression as possible without taking away the smoothness.

What I wanted was something with a bit more personality and dynamics, so we removed a lot of the compression and high-end emphasis

“I think high-end emphasis is a real consumer kind of thing. In order to get you sounding more like recorded music, when you’re playing at a low volume in your apartment, there’s a post-EQ pre-power amp stage presence that’s added. It’s there from stage zero to about eight and then it kinda disappears, but it also undermines the dynamics that you need. Play with a drummer and they’ll go from zero to 125dB - you can’t have an amp set at one level that can’t get louder with just the stroke of your hand.

“I didn’t feel that was a professional-grade setup, though I understand why it’s done… 90% of the market or more is made of enthusiasts and amateurs. There’s very few of us professional players using 100W heads turned up loud.

“What I wanted was something with a bit more personality and dynamics, so we removed a lot of the compression and high-end emphasis to create a professional tool that I’ve used every night. I run one head into two 4x12 cabinets.”

Ibanez JS1

“The original JS1 was and still is so important to me. They generously allowed me to make contour changes, modify the radius - as well as introduce a multi-compound radius neck - use different-sized frets, keep the Edge trem system, bring in DiMarzio pickups designed for me by Steve Blucher.

“Even the choice of Japanese basswood for a tight response, all of these things were important for me in creating impressive melodies, while also staying in tune, haha! This was the first step of the JS line… looking back, it really was take-off.”

Ibanez JS2450

“Years later, moving up to 24 frets felt like another big leap. As was going with a different body wood - I was trying to figure out why I couldn’t get the JS to replace classic sounds coming from the four different instruments designed in the ’50s: the Tele, the Strat, the Les Paul and the 335. Honestly, nothing can completely replace them - if you want to sound like a Les Paul, you have to get one.

Sound engineers would always tell me how that orange guitar sounded incredibly centred out front

“But I was just looking for hints of each sound, and looking closer at the Gibson solidbody guitars, like a Junior or SG, as well as Teles and Strats, we realised the wood is extremely important. For a while, we had the JS6 all-mahogany guitar, which was really interesting and got a lot of work on The Extremist and Chickenfoot records. Ultimately, I realised alder is what I was looking for.

“When we started the Muscle Car paint series, they all had alder bodies, which gave much more focus to their sound. It became apparent in the studio as well as live, when sound engineers would always tell me how that orange guitar sounded incredibly centred out front.

“It was strong enough to make it through the amp, speakers, microphone, into the front of house and to the audience. It’s one of those rare instances of change where it effects more than just the player, it felt apparent to the audience… which was always the goal!”

Ibanez JS1CR30

“This year, we announced the JS1CR30 – the new Chrome Boy guitar. It’s made out of alder and plated in chrome, with a Sustainiac Driver neck pickup that comes stock. It also has larger and fatter frets, so feels like another step forward in modernising the JS series without losing the groovy shape or playability or ergonomic qualities about it.

“All the good things are there - it’s dynamic, comfortable, and the pickups are actually better, too. We went for the DiMarzio Satchur8 in the bridge, also made one in collaboration with Steve Blucher, who made me something even bigger and wider-sounding than anything before. Plus… these guitars just look so damn cool!”

Amit has been writing for titles like Total Guitar, MusicRadar and Guitar World for over a decade and counts Richie Kotzen, Guthrie Govan and Jeff Beck among his primary influences. He's interviewed everyone from Ozzy Osbourne and Lemmy to Slash and Jimmy Page, and once even traded solos with a member of Slayer on a track released internationally. As a session guitarist, he's played alongside members of Judas Priest and Uriah Heep in London ensemble Metalworks, as well as handling lead guitars for legends like Glen Matlock (Sex Pistols, The Faces) and Stu Hamm (Steve Vai, Joe Satriani, G3).