Carol Kaye in the '60s, with a Fender Precision and go-go boots, workin' on a groovy thing...and another Top 10 hit.

Some folks have to pad their resumes, but in the case of Carol Kaye, who from the 1950s and into the 1970s was one of the busiest session musicians around, laying down distinctive bass and guitar tracks on scores of Top 10 smashes and literally thousands of recordings, even a bullet-point sampling of her accomplishments boggles the mind.

Phil Spector, The Beach Boys, Ray Charles, Simon & Garfunkel, The Monkees, Joe Cocker, Sam Cooke, Barbra Streisand, Frank Sinatra, The Supremes, Glen Campbell, Sonny & Cher, Lou Rawls...just some of the artists who benefited from Kaye's low-end fretboard magic.

Next we have Kaye's equally impressive work in film: In The Heat Of The Night, The Pawnbroker, The Thomas Crown Affair, In Cold Blood, The Long Goodbye, Butch Cassidy And The Sundance Kid and dozens more. As for the small screen, you've heard Kaye on themes like M.A.S.H., Mission Impossible, Ironside, Hawaii 5-0, The Brady Bunch, Hogan's Heroes, The Addams Family - here, too, the list goes on and on.

Often called the Queen of Bass or the First Lady of Bass, Kaye, a woman very much in what was then a man's man's man's world, was an integral part of the group of Los Angeles-based musicians that drummer Hal Blaine dubbed "The Wrecking Crew" (a tag Kaye disowns). Since retiring from active studio work, she went on to become an in-demand instructor and best-selling author of instruction books.

As it's Bass Week on MusicRadar, we can think of no one better to kick things off than Carol Kaye. In the following interview, she remembers the glory days of the '60s, when she worked with some of the biggest names around. "People were surprised to learn that this little white girl was playing such funky, groovy stuff on a bass," she says. "But I was just doing what came naturally."

How did you start playing sessions?

"I was a guitar player. I had been playing since the age of 13. By 18 or so, I was out there playing gigs - jazz and bebop. It was a good way to learn and improve my ear and my ability to improvise. When somebody looked at you and said, 'Play!' well…you had to play! [laughs]

Plus, the gigs paid well, so it put food on the table. My family didn't have much money. I had gotten married very young, had two kids, and by the age of 21 I was divorced and was living back with my mother - with my two kids.

"At that time in Los Angeles, there were hundreds of clubs and places to play. It wasn't like it is now. If you were good and wanted to play, you got your chance. I was a white girl with blonde hair, but I was welcome in the black clubs. If you could play, then you were welcome. And I was welcome.

"I wasn't really looking to do sessions, because I was getting a good name in the jazz clubs. But this producer, Bumps Blackwell, came in and said, 'You want to do a record date?' By this time, rock 'n' roll was getting into a lot of clubs, so I figured I would do the session. It turned out to be for Sam Cooke."

A familiar sight in 1955: young Carol Kaye, bebopping in a nightclub.

Not a bad first record to cut.

"No, no, it wasn't. It was a nice way to get my feet wet, especially playing a soul session. It was a good, easy introduction to the studio. Sam Cooke was incredible. What a great singer! So that's how it started for me. Everybody liked what I did, and I liked doing it, so I started playing record dates."

Was the fact that you're a woman an issue at all? One would think, at that time, that session work was very much a boys' club.

"No, it wasn't an issue. It was just like it was when I was playing gigs: If you could play, you could play - that's all there was to it. People knew I wasn't somebody's girlfriend or some hanger-on that shouldn't really be there.

"Plus, they needed good guitar players. In the beginning, I wasn't first-call or anything, but very quickly people could tell that I had the talent and that I could learn parts fast - and come up with parts. By 1958, '59, I started working heavy, and it was nothing but guitar dates."

How exactly did you switch over to bass?

"I was playing a session at Capitol Records, and the bass player didn't show up. So, they put me on a Fender bass - easy as that. I started creating lines that I always heard in my head, things that I thought bass players should play. I just provided what the music needed.

"This was pretty important during some of the early rock 'n' roll dates. A great singer like Sam Cooke, you didn't have to do too much to what he did. But some of the rock sessions, if we didn't add some interesting lines, the songs would've sounded very flat. The music needed a little help, and so did the singers." [laughs]

So playing the bass came pretty easily to you, even after being a guitarist for a while?

"Yeah, I would say so. It felt comfortable. I think the fact that I was a jazz player really helped. I thought melodically as well as rhythmically. I knew lines and how to shift around with the music. I wasn't just stuck on any one chord. I developed a feel and a touch - and a sound.

"Honestly, what I liked about the bass was the fact that it had four strings. [laughs] It's true! Also, I dug being on the bottom of the band. It was my own little spot. I knew what to do and what to invent. Not only that, but I was getting tired of bringing four or five guitars to sessions. With the bass, I only had to bring in one thing. Nothing hard about that."

You played on many Phil Spector records. What was it like to work with him?

"Phil was a pretty nice cat at first. He was so young and determined. I met him in the clubs years earlier. I had my bebop jazz thing, and he came up to me and said, 'I love the way you play.' He invited me out to his house, where I met his mom. He played me a couple of tunes and said he'd love to have me play on them. I listened to them and said, 'Yeah, I could help you out here.'

"Working for Phil was great. I played guitar, 12-string guitar, bass - whatever was needed. Even when I played guitar, I played the bass, if you know what I mean. Phil had so much echo going on - even in our headphones we heard it - so on You've Lost That Loving Feeling, even though I was playing the guitar, I had to help the bassline. I was going, 'Bump…Ba-bump…Ba-bump…Ba-bahh-bum-bump!' You know? It was bass on the guitar."

Obviously, you had no idea that You've Lost That Lovin' Feeling would be a classic, but did you sense at the time that it was special?

"Oh, yeah. You can feel greatness. When great hits you, you know it. The whole vibe of that song was something else. We could tell when we were cutting the song that it would be a number one hit, no doubt about it. But you have to remember, at that time, everything Phil Spector did went to number one. He couldn't miss. When you got on a Phil Spector date, you were going to be working on a smash."

Would Phil write out charts?

"He had some charts, but not all the time. There'd be people like Gene Page or Jack Nitzsche who would do charts for him. Phil would show us some things, but they weren't always written out. He'd try to hire the people for what they could do. Phil knew I would lay down the groove. If I got the rhythm going, he knew it was happening."

Did Phil display any of the, uh, eccentricities that would later get the best of him?

"He wasn't crazy back then. He was...strange. Half of the people in the studio loved him, the other half couldn't stand him. I was somewhere in the middle. He started seeing a shrink at one point and would practice his shrink-talk on us. But he was nice to my kids - I brought them to sessions sometimes."

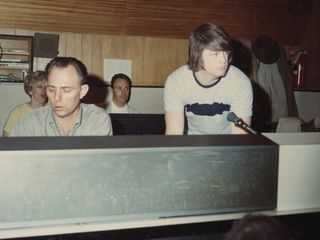

Front-row seat for greatness: (from left) Kaye in the control room with engineer Chuck Britz, musician Bill Pitman and Brian Wilson.

One of Phil's last big productions from the '60s was River Deep, Mountain High. It was supposed to be his masterpiece.

"And I played on it, too. That whole thing felt like one big party. There were so many people in the booth and the main room, but you know, when things get that out of line, you sit there going, 'Uh-uh…this isn't going to be a big hit.' I don't know, you could just sense that the song itself needed to be nailed down. It was very big and busy, but it was too busy. It didn't have the immediate thing that his other songs had."

Eventually, the group of musicians in these sessions were what Hal Blaine dubbed 'The Wrecking Crew.'

"Yeah, but there wasn't really a set bunch of people in that ensemble. I know Hal called it The Wrecking Crew, but we never called it that, nor were there only so many people in the gang. There was never a band. Never. Different people were used for different dates. If we called the group of musicians anything, it might have been 'The Clique.'

"The group of people that Hal is referring to wasn't some small little thing, it was more like 50 or 60 people, all of them the premier players in Los Angeles at the time. We were totally freelance, and we never worked at the same time."

What was working with Brian Wilson like? You did more than a few Beach Boys sessions.

"Brian was fabulous. What a dear, sweet man, and such a brilliant musician. He liked my bass playing. He was a bass player himself, but he was getting so busy writing material and producing that it was hard for him to think about playing, so he had to use other people.

"I was becoming known as the hit bass player. They had been hiring three bassists for sessions - a Fender player, a string player and a Dano player - but pretty quickly, people started finding out that they only had to hire me and I'd get all the sounds for them. Brian liked that idea, but he also liked my lines. He wasn't just a sound guy, he was a concept guy."

On something like California Girls, for example, what kind of direction would he give you?

"Brian would come in and play the song on piano. He'd sing it a little bit, but sometimes he didn't have all the words. But he'd play through the tune and give you the idea. He'd have things written down, too. He was the one guy who had my parts written down.

"He would keep my bass sound way up in the mixes. On a song like California Girls, at times you can hardly hear anything else. He just liked my sound and the way I moved around the fretboard."

When you played on something like Help Me, Rhonda, was the session fun?

"Well, it was fun because Brian was fun and he was a sweet guy. It was work, though. Actually, that particular song was something else because Brian had us do an eight-minute take. You don't ever work the band for eight full minutes. We're giving you our all. At eight minutes, you start to lose it. Particularly with the part that I was playing, which was fast and bouncy."

What about Good Vibrations? How did that session go down?

"It wasn't just one session, it was more like 12! [laughs] Ray Palmer did the first session, but his playing wasn't used. We did 12 more dates on Good Vibrations to get it right where Brian wanted it. I played just what he had written out. There's string bass, too, but you don't really hear it. What you hear on the radio is me on my Fender Precision - that's what Brian wanted me to play."

Sonny & Cher's The Beat Goes On - you invented the famous bassline.

"That's right. You know, when that tune first came in, it was a dog. [laughs] It really was. Sonny Bono was a good man, you know? A good, good man. And I really liked Cher a lot, too. But they weren't the best of singers. There wasn't a lot going on in the song, so it needed some help.

"Bob West was on bass, and I was playing the Dano bass, which I approached as a guitarist even though it was technically a bass. Bob had been a tremendous jazz bassist, so we knew each other quite well, but he was just playing this boring old one-note part. I thought it was terrible! So I just started playing this line - all of a sudden, the thing came alive! It shocked me, too."

Back in the '60s, what was a typical day for you?

"It was busy. I'd do two, three and four dates a day. A date was three hours. So there'd be something from 10am to 1pm, then something from 2 to 5, and then we'd a session from 8 to 11 at night. Between 6 and 7pm, we'd to squeeze in a commercial or something. That meant you didn't go home for dinner with the kids. Now, the film calls were at 9am, so there were early days and late nights."

Was working on film and TV scores very different from the songs and albums you were cutting?

"It was a different crew of people calling the shots a lot of the times. Quincy Jones was one of the big guys doing films and TV shows. He knew I was playing on all the hit records, and he liked my sound and feel. He needed that hip bass sound, something that was very 'now' and funky. Plus, he knew I could sight read, which some of the other players couldn't.

"The biggest thing to working in film and TV came down to three words: 'Don't be late.' If you held up a film score, you were costing a film company a lot of money. Dozens and dozens of musicians - sometimes a whole orchestra - would be waiting there…for you! Excuses didn't matter."

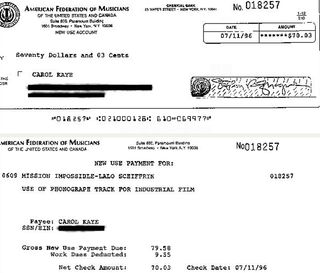

A residual check for Mission: Impossible. One of many...

Even though you said you were accepted in the sessions, was it ever hard to hang out with guys all day and all night?

"No, it was easy. Some guys would get macho. Tommy Tedesco would toss a few cuss words my way, but I'd throw them right back at him. After that, he was OK. Hal Blaine loved to swear a lot, and he was quite proud of that. So I learned to out-swear him, which I'm not proud of, but I was doing what I had to do."

During the golden period of the '60s, was the Fender Precision your main bass?

"That and the Dano. It's funny, because I was so busy that I didn't even have time to change the strings. I would run into a music store on a five-minute break and have them do it for me. Either that or I would pick up another bass that they had and use that. Changing strings…I just didn't have time! But the Precision was a big instrument for me. That's the one everybody wanted."

As a rule, would you follow the drummer - say, Hal Blaine?

"Uh-uh. To me, the bass sets the mood of the song. The bass player drives the band. I might have been slightly influenced by the drummer, but I was really paying attention to the song and the singer. If Hal or anybody played a certain fill on a drum, I wasn't going to follow that."

Did you have a good relationship with Hal back then?

"We were buddies in a professional sense. Personally, I was never that close to him. Earl Palmer, one of the other drummers, now he was a close friend. Hal was a different kind of a cat. He was a fine drummer, but he…I don't know. A woman senses certain things about a man. We were professional, Hal and me. I just wasn't into hanging out with him."

Glen Campbell played with you on a bunch of dates before he became a solo star. Good guy?

"Oh, Glen was fantastic. What a funny guy! He would crack us up all the time. During breaks, Glen would sing us all these dirty country songs to make us laugh, and boy, did he have us going! But what a guitar player. He was great at rock 'n' roll soloing."

A recent shot of Brian Wilson with Kaye.

When did you see the days of The Clique ending? Do you remember the sessions starting to dry up?

"It was during the late '60s and early '70s. The music started to change and the way it was being recorded did, too. The bands were self-contained and they didn't need so many outside players. I saw it starting to happen and I got out. Tommy Tedesco thought I was crazy. He said, 'You're at the top of the heap, Carol. Why are you quitting?' But I couldn't stand the cardboard music we were being asked to create.

"To me, once the Charles Manson murders started happening in the Hollywood Hills, and then you had people getting mugged on the way to the studio, all of that changed the scene. Things weren't fun anymore. Hollywood wasn't safe. That was the end of that for me."

Do you ever think a group like The Clique could ever happen again?

"No. Times are way different now. We were from the '40s and '50s, from the nightclubs. People can't play the clubs like we did then. The whole industry has changed in the way music is booked and promoted. Folks don't go and hone their craft now. We played in front of people every night. That was our schooling. It was a great time."